Toledo art museum to give back rare jug

Vessel looted from Italy, inquiry finds

6/20/2012

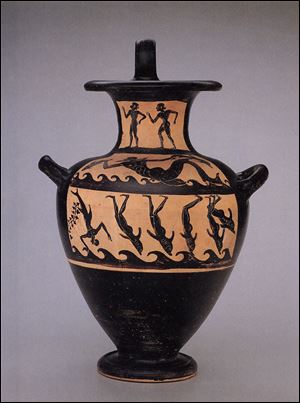

The 20-inch-tall water jug has been on view at the Toledo Museum of Art since its purchase in 1982. The painting on it depicts the Greek tale of Dionysos, god of wine and drama. The museum will return it to Italy soon.

A rare 2,500-year-old water jug will leave its 30-year home at the Toledo Museum of Art for Italy soon, its return prompted by an investigation that determined it had been looted from Italy.

The graceful 20-inch-tall clay piece, called a kalpis, or water vessel, has been on view almost continuously since its 1982 purchase. Painted in black against the orangey clay is a sophisticated rendering of the ancient Greek tale about young Dionysos, god of wine and drama, who was kidnapped by pirates. To evade his wrath, the pirates leapt off the ship and are shown being transformed, in midair, into dolphin-headed men.

It's believed to have been crafted by a talented Etruscan artist (whose work is also owned by the Vatican) in southern Italy or Sicily, where Greeks are thought to have migrated. The museum considers it among the 300 most precious of its 30,000 objects.

A consent order is expected to be filed today in U.S. District Court in Toledo, stating that the museum will relinquish the kalpis for return to Italy.

"The right thing to do is to return this object," said Brian Kennedy, museum director. "We knew we'd likely lose this. We'll miss it."

The kalpis will be prominently displayed in Libbey Court until it leaves, probably in late summer, for display somewhere in Rome.

The problem is that before it came to Toledo, it was smuggled from Italy to Switzerland. On top of that, its record of ownership (called provenance) was forged.

The investigation into this and dozens of other Italian objects dates to 1995, when Italian police searched the Geneva office of an antiquities dealer and found thousands of photographs of apparent antiques, many covered with dirt as if they'd been recently unearthed.

Those photos were matched with images of objects bought by U.S. museums.

The items were probably excavated illegally, sold to middlemen and dealers, and ultimately purchased by unwitting but eager museums and collectors, noted Mr. Kennedy, who developed a thick dossier doing his own research on the case.

Recommending Toledo buy the kalpis for $90,000 was the late museum curator Kurt Luckner, said to have had a good eye and an ear to the ground when it came to acquisitions. He heard it was for sale from Ursula Becchina, a prominent dealer who, with her husband Gianfranco Becchina, specialized in Sicilian antiquities and worked out of Switzerland. It was a coup for Toledo because the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York had also wanted it.

But the kalpis' key documentation was stunningly scant: a photocopy of two paragraphs typed in German on hotel stationery by the Swiss hotel's owner, stating he had owned it since 1935. A 1939 Italian law said all archeological finds after 1939 are property of Italy. At some point the kalpis was spirited out of Italy to Switzerland, from where it was shipped to the museum.

Decades later, Mrs. Becchina would admit that she and her husband forged documents and that he bought antiquities from Italian diggers and others.

Today's American curators would run from such "documentation," but 30 years ago, museum staffs had different standards, Mr. Kennedy said. "The issue is that illicit markets are not supported anymore by U.S. museums. The aim is to choke the trade."

In 1992-93, the museum sent the kalpis to exhibits in Paris and Berlin, and in 2001, a curator took it to Venice for a show about the Etruscans. While it was there, the museum received a subpoena from an assistant U.S. attorney in Toledo asking for its documentation, so the museum's registrar flew to Venice to bring it back.

Over the next several years, the Italian government made moves to recover some of their ancient works. Objects at the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and others were targeted, as was the kalpis.

In 2005, Don Bacigalupi, then museum director, said that if the vessel was stolen it would be returned. Many museums were approached and returned objects, including 14 from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2008.

Since 2007, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Customs and Border Protection have returned more than 2,500 items to more than 23 countries.

The current phase of the Toledo investigation began in April, 2010, 10 years after the initial inquiry, when an agent in the immigration and customs agency's Cleveland office who specializes in cultural property called to say he'd be at the museum the next day to talk about the kalpis.

Disturbing to Mr. Kennedy and Carol Bintz, the museum's chief operating officer, were three threats between November, 2010, and January, 2012, that if the object wasn't handed over, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents would seize it. Mr. Kennedy likened it to a drug bust. Each time, the museum asked for additional proof or a chance to work out a culture-exchange with Italy.

"When I came in [to the case], they felt they had investigated it fully enough and they didn't feel they needed to share that information with me," Ms. Bintz said. At first, Immigration and Customs Enforcement provided only poor-quality copies of photos.

Neither ICE nor the U.S. Attorney General's office would speak with The Blade about the case before today's filing.

In February, Ms. Bintz and Mr. Kennedy met with the federal agent and others, asking for more evidence, some of which Mr. Kennedy had turned up himself. By March, Immigration and Customs Enforcement had furnished additional evidence: Mr. Kennedy was satisfied and the museum board agreed to return the vessel.

A museum must prove its innocence, he said, but Immigration and Customs Enforcement needs only to provide "probable cause" before seizing an object.

This case is the second time in the museum's 111 years it has returned an unwittingly ill-gained object. In February, 2011, a sensuous mermaid holding a candy dish, the Nereid Sweetmeat Stand, was returned to the Dresden Museum in Germany. Made in the mid-1700s, it had been stolen during World War II.

That case was scientifically based, said Mr. Kennedy: New X-rays of the porcelain piece showed fine cracks that matched photographs taken in the 1930s when it was still in Germany. The Toledo museum returned it to the Dresden Museum last year.

Museum insurance does not cover the losses. Mr. Kennedy said no other museum objects are being considered for repatriation.

He noted such cases raise questions: Should people be able to see Italian antiquities only in Italy? Should a one-of-a kind object in Toledo be returned to a country that has numerous similar objects? Should there be an end-date to repatriations? And should Immigration and Customs Enforcement be permitted to seize items from American museums for probable cause?

Contact Tahree Lane at: 419-724-6075, or tlane@theblade.com.