The anti-social side of social media

From trolling to insults, the rise of social media has brought out our nasty sides

10/16/2016

Editor’s note: This story has been edited to correct the spelling of Rachael Ray’s name.

None of us were there, yet we all took a side.

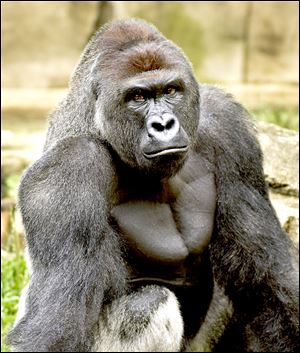

We’re talking about May 28 of this year, when the Cincinnati Zoo killed a gorilla after a toddler climbed into its enclosure.

The social media storm over the death grew so loud that three months later Time magazine published the article “Harambe the Gorilla Is Dead. Get Over It,” in which it characterized the Internet trolls — those alternately attacking zoo officials and the child’s parents — as “lazy activists at best and bullies at worst.”

Frank Goforth of Holland took part in that social media conversation. Though he kept his remarks civil, he had an acquaintance “unfriend” him on Facebook because the person thought he was taking sides when he asked a group of friends to civilly discuss the event.

Harambe

“I posted my opinion. I had seen what happened, and from my standpoint I was disappointed by the way it was handled by the zoo. It is one of those things [where] I think no one ever wants any life lost whether a child or animal,” the 30-year-old said.

“Really intense conversations” were sparked over the zoo killing of Harambe. Some friends argued Harambe should have been spared, others argued the zoo made the right call in shooting the gorilla to ensure the toddler’s safety.

“By the time I got there I was debate moderator. I was like, ‘You guys have to stop,’ because it got nasty,” he said. There was swearing, shaming, name calling, even “challenging each other’s intelligence. It was bad.”

Debates are part of the American fabric, and “We The People” have taken pride in partaking in blistering discussions to defend our politics, religion, and myriad other choices. But some of us might never have such an exchange with Aunt Betty or Uncle Frank or even some of our closest friends were it not for the Internet.

Mr. Goforth said he would still have those discussions face-to-face but that social media has “increased the frequency 100 percent.”

Uncivil conversations didn’t begin or end with Harambe. More recently, social media commenters are blaming Kim Kardashian for being robbed, and, of course, the the biting debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump supporters seem never-ending.

The Nasty Effect

Brossard

Persuasion studies have consistently shown that aggression will not convince people to change their minds. In fact, the rude route will most likely make them more convinced they are right and that you are against them, said Dominique Brossard, professor and chair in the Department of Life Sciences Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

She and a team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Virginia’s George Mason University led a study that explored the “Nasty Effect.”

They found that when readers were presented with a scientific article, unbiased and factual, written by a professional journalist and then exposed to either nice or rude comments, the nasty comments not only polarized the readers but also colored their view of the article as biased. That is the Nasty Effect.

“So you are here trying to write a good story, interviewing news sources, being as balanced as possible, then your story follows with very rude comments, compared to stories that don’t have those very rude comments. ….Well those people that read the rude comments they end up even extending the malaise. The messiness that they see in the comments ends up coloring their perception of the story and of the issue covered in the story,” she said.

She said not to underestimate the power of online cues that did not exist in traditional journalism. Their research paper — “The ‘Nasty Effect:’ Online Incivility and Risk Perceptions of Emerging Technologies” — also looked at likes, reTweets, and so on.

“It is like thinking in terms of 15 years ago. You were reading the Toledo newspaper in a coffee shop by yourself and you had people around you that were yelling at you saying: ‘This!’ ‘This and that!’ or ‘Lalalala!’ Imagine this is what is happening in the online environment,” Ms. Brossard said.

Though some newspapers and media outlets have recognized the hectoring nature of modern commenters and shut down the ability of readers to respond online (NPR recently enforced such a ban), the educator said these sites have not necessarily banned negative comments, merely moved them somewhere else.

Some newspapers like the New York Times and The Blade have staff that comb through comments to ensure readers are abiding by established guidelines, such as no profanity. But what of the social media companies themselves? How much policing should they do?

An email response from Facebook said it also has standards and relies heavily on users to report inappropriate content.

Facebook and social media came into play when President Barack Obama ran for office in 2007, then mainly as a way for politicos to reach the public. Today, it has become a place for the public to exchange opinions and debate issues, often in vitriolic terms.

Facebook said that from Jan. 1 to Oct. 1, 109 million people in the U.S. generated 5.3 billion likes, posts, comments, memes, and shares related to the 2016 presidential election.

The mob effect

Shahin

In the case of Harambe and other social media controversies, it often seems like a mob mentality takes over the Internet and people start attacking each other virtually, said Saif Shahin, assistant professor of digital journalism at Bowling Green State University.

Opinion is peddled as fact, leading social media users to, for example, mistakenly attack celebrity chef and talk show host Rachael Ray in April thinking she was a mistress that Beyonce sang about in “Sorry;” or giving license to trolls to target Ghostbusters co-star Leslie Jones on Twitter, some even threatening to cut off her head.

Professor Shahin said that mob mentality happens most often on platforms like Twitter, where it can provide anonymity.

Through Twitter hashtags, groups can communicate about an issue while not necessarily following each other, he explained, while Facebook users have more control over who can see their posts.

“In theory all of them are open to everybody, but in practice our Facebook connections are people whom we already know offline,” he said.

He said anonymity combined with the absence of physicality is a recipe for disruptive behavior.

“In a physical context, when you are in front of people that you personally know, that is not going to happen generally. We don’t see this happening in day-to-day life, but it happens on social media,” he said.

He said those engaging in the uncivil discourse don’t see it as engaging in mob behavior. He believes they are acting out of self-righteousness.

“They think they know what’s right and the other person doesn’t and therefore they need to tell the other person: ‘You need to do this or you’re wrong,’ ” he said.

The big picture

Surprisingly, the generators of many of these organized furies are adults, said Diana Graber, founder of cyberwise.org and cybercivics.com, which advocate for digital citizenship among children nationally.

“I don’t understand why adults don’t do what I teach kids to do: Before you post something stop and think; there is a real person at the other end of your post whose feelings could be hurt,” she said in a phone interview from her home in Capistrano Beach, Calif. “This is what we teach our kids, and I don’t understand why the lesson has not trickled up to parents.”

Remember, she added, “Everything we post reflects upon our online reputation.”

Erin Vogel, PhD candidate in the University of Toledo’s social psychology program, said social media users should realize they are only viewing a snippet of someone’s life.

“They are only seeing what we choose to present on social media. They may be attacking someone for that one political opinion or one thing that they posted,” she said. She cautioned that users on the end of an attack should also realize that attacks are not necessarily directed at who they are as a whole person.

Research shows that social media is most rewarding when one interacts with people they know and like, Miss Vogel said.

While many experts tout the positive uses for social media, especially to incite people worlds apart to work collectively for good causes, Lisa Hanasono, assistant professor of communications at BGSU, warned that it is also a conduit for misinformation and can impede deep discussions about political issues.

“The overarching rhetorical question is: how deeply engaged can we be on any issue with just 140 characters?” she said of Twitter.

Ms. Hanasono also warned users that Twitter and Facebook are both businesses. Like any business, they want to satisfy the client. Social media platforms are structured with algorithms that make sure when you scroll through posts you are more likely to view newsfeeds that reinforce your views.

“In some ways, that can embolden people to feel their perspective is right because they see people posting that it is right. They might not see as often the broader information on the topic,” she said.

Finally, she advises users to complement social media with offline and face-to-face conversations.

Contact Natalie Trusso Cafarello at: 419-724-6133, or ntrusso@theblade.com, or on Twitter @natalietrusso.