Jon Hendricks, 'poet laureate of jazz,' dies at 96

11/23/2017

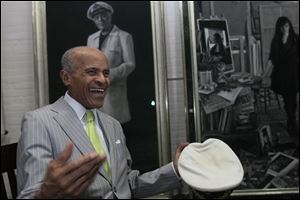

Jon Hendricks sings with University of Toledo jazz musicians in 2014. Hendricks died Wednesday at the age of 96.

The Blade

Buy This Image

Jon Hendricks, a singer and composer who developed an intricate style of vocal gymnastics to match his tongue-twisting lyrics and whose Grammy-winning vocal trio, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, is widely regarded as the most influential singing group in jazz history, died Nov. 22 at a hospital in New York City. He was 96.

His publicist, Don Lucoff, confirmed the death. The cause was not disclosed.

Jon Hendricks sings with University of Toledo jazz musicians in 2014. Hendricks died Wednesday at the age of 96.

Once dubbed the "poet laureate of jazz," Hendricks expanded the vocabulary of jazz singing as the leading exponent of a style known as vocalese. He wrote witty lyrics for dozens of jazz tunes that otherwise had no words. Moreover, as a vocalist, he performed at breakneck speed, winning the admiration of such jazz giants as pianist Art Tatum and saxophonist Charlie Parker.

Well into his 90s, he was a vibrant presence in jazz - "the epitome of hip," music critic Scott Yanow observed.

In his life as well as his music, Hendricks embodied the spirit of improvisation: He grew up in a household of 15 children, began performing at 11 and, after enduring racial taunts as a soldier during World War II, was jailed for desertion and for running a black-market smuggling ring. He was considering law as a career when Parker, the innovative bebop saxophonist, told him, "You ain't no lawyer. You're a jazz singer."

Hendricks did not possess the classically smooth vocal style of balladeers such as Billy Eckstine and Frank Sinatra, but instead made the most of his dry, raspy tenor voice and an intense feeling for rhythm.

Largely through his innovative work with Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, he exerted a formative influence on generations of jazz singers, from Mark Murphy and Al Jarreau to Dianne Reeves, Bobby McFerrin, Kurt Elling and Tim Hauser of the vocal group Manhattan Transfer. Lambert, Hendricks & Ross created what music critic Will Friedwald called "some of the most sensational jazz ever sung."

Vocalese had been around for years, but it gained currency in jazz in the early 1950s largely because of "Moody's Mood for Love." The singer and lyricist Eddie Jefferson had composed a completely new song based on James Moody's saxophone solo on "I'm in the Mood for Love."

At the time, Hendricks was patching together a meager living as a songwriter and occasional singer. He composed the music and lyrics of "I Want You to Be My Baby," which became a rhythm-and-blues hit for Louis Jordan and Lillian Briggs, and a few other tunes.

But it wasn't until he began to work with Dave Lambert, a bebop-oriented singer and arranger, that Hendricks found his niche in vocalese. In 1956, they received a recording contract for a vocal album built around the music of Count Basie.

Jazz musician Jon Hendricks in figurative artist Leslie Adams' Toledo studio in 2013.

In the studio, they discovered that, with one exception, the singers in the choir could not manage the elastic rhythmic concept known as swing - the essential element of jazz. The exception was the British-born Annie Ross, who had a large vocal range and a jazz musician's sense of timing - and had written the vocalese classic "Twisted" in 1952.

Lambert and Hendricks asked Ross to join them and form a trio. Together, they overdubbed all the parts for the Basie project, recreating the sound of a big band with their voices. It was one of the first times multi-tracking had been used for a vocal recording.

Lambert, Hendricks & Ross's bravura performances on "Sing a Song of Basie" went beyond anything that had been attempted before. The album became a phenomenon when it was released in 1958.

During their five years together, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross recorded six albums and became international stars - and were also one of the first integrated singing groups in jazz or popular music.

Their final album in their original lineup, "High Flying" (1962), won a Grammy Award. In 1998, "Sing a Song of Basie" received a special commemorative Grammy.

As the group's primary lyricist and songwriter, Hendricks helped push jazz singing to new heights of virtuosity.

"When I was first singing, I would forget the words and then make up ones I thought would fit," Hendricks told jazz writer Ralph Gleason in 1959. "When I put in my own words, I found out that as long as they rhymed, people didn't know the difference."

Although he never learned to read musical notation, Hendricks wrote the lyrics for more than 50 songs recorded by LH&R, including the coolly relaxed "Li'l Darlin'," associated with Basie; the boppish "Four," identified with Miles Davis; and Horace Silver's punchy "Doodlin'," which was something of a comic ode to unconscious creativity:

Sittin' and dinin', dinner beginnin'

Started designin', usin' the linen

Talkin' to my date, doodlin' my bit

Waiter got salty, told me to please quit

Told the waiter, "Don't be dizzy

"Can't you see, I'm very busy

"Doodlin' away . . ."

Judith Hendricks, Jon Hendricks, Michelle Henricks, and Bob Garland in 1982.

In 1959, Hendricks composed a set of lyrics to match the propulsive turns of Ben Webster's tenor saxophone solo on "Cotton Tail," a 1940 tune by Duke Ellington. Written from the point of view of a rabbit sneaking into a farmer's garden to nibble carrots, the words transform the song into a jazz equivalent of a Bugs Bunny cartoon:

In the garden where carrots are dense,

I found a hole in the fence.

Every mornin' when things are still,

Gonna crawl through the hole and eat my fill.

The other rabbits say I'm taking dares

Maybe they're right, but who cares?

I'm a hooked rabbit!

Yeah, I got a carrot habit.

John Carl Hendricks was born Sept. 16, 1921, in Newark, Ohio. His father was an African Methodist Episcopal pastor who settled in Toledo.

Hendricks, who adopted the more eye-catching spelling of Jon for his first name, sang in church at a young age and by 9 was taking lessons from a neighbor - Art Tatum, one of the great virtuosos of jazz piano.

"All the kids would go out and play," Hendricks told the Associated Press in 1996. "Here I was being blessed with the greatest musical education you could have on this planet. . . He would play runs and say, 'Sing that.' I would shut my eyes and sing it until I got it right."

Drafted into the Army during World War II, Hendricks served in France after the Normandy invasion. But his most harrowing wartime experiences came from mistreatment by white soldiers in his own army, he recalled more than six decades later to Lee Ellen Martin, a University of Toledo graduate student writing a thesis on the singer. Hendricks said U.S. military police officers fired at him and other black soldiers they suspected of consorting with French women.

Out of fear, the black soldiers fled their unit. As a battalion clerk with access to military papers, Hendricks said he requisitioned a car and two trucks, loaded with gasoline, food and other supplies. He and the other African-American soldiers sold the goods on the black market for several months before they were arrested and charged with "desertion in the face of the enemy."

"What enemy?" Hendricks said he responded. "You mean the white military police firing on us?"

After almost a year in a military stockade, he was released and reinstated in the Army. After the war, Hendricks went to the University of Toledo on the G.I. Bill while also performing as a jazz singer and drummer.

When Parker visited Toledo, he was so impressed that he issued a standing invitation for Hendricks to look him up in New York. More than two years later, after his educational benefits ran out, Hendricks went to New York and found Parker performing at a club in Harlem.

"And as soon as he saw me, after all that time," Hendricks told The Washington Post in 1980, "he said, 'Jon Hendricks, come on up and sing a little.' "

Lambert, Hendricks & Ross had five years as the top vocal group in jazz before Ross left in 1962. Lambert and Hendricks forged ahead with other singers for two years. Lambert died in 1966, after being struck by a car while helping a motorist change a tire.

Hendricks lived in Europe from 1968 to 1973, in part to provide a better educational and social climate for his children. He later lived in Northern California and New York. When he wasn't working as a solo artist, he often appeared in small ensembles, sometimes with his wife, Judith, and some of his children.

Jon Hendricks sings with University of Toledo jazz musicians in 2014.

His first marriage, to Colleen Moore, ended in divorce. His second wife, the former Judith Dickstein, died in 2015 after 56 years of marriage. Two children from his first marriage, Colleen Hendricks and Eric Hendricks, have died.

Survivors include two children from his first marriage, Jon Hendricks Jr. and Michelle Hendricks; a daughter from his second marriage, Aria Hendricks; and three grandchildren.

Hendricks, who recorded well-received albums featuring his compositions, wrote the lyrics for Manhattan Transfer's 1985 album "Vocalese," which won several Grammy Awards - including one for Hendricks and McFerrin for their performance of "Another Night in Tunisia."

In the 1990s, Hendricks was featured in a recording and in live productions of Wynton Marsalis's Pulitzer Prize-winning jazz oratorio, "Blood on the Fields." He was named a Jazz Master of the National Endowment for the Arts, the country's highest honor for jazz musicians.

He toured with singers Kurt Elling, Kevin Mahogany and Mark Murphy, billed as "The Four Brothers," and was featured in a 2009 documentary, "Blues March." Hendricks taught jazz singing at the University of Toledo from 2000 to 2015.

From Tatum to Marsalis, Hendricks shared the stage with many of the greatest musicians of the past century. The only one time he couldn't hold his own was during a jam session with singer and comedian Martha Raye.

"She starts scatting, and she's trying to cut me," Hendricks recalled to Jazz Times. "I was laughing. She was scatting like, 'Spack! Shog-in-dit Dit! Shadle-do-bom-bop dee-ter. Shpee-keee do-ah-da-wop! Then she put the huge old microphone completely in her mouth. Man, I got off the bandstand!"