Ramones rocked our world

3/31/2005

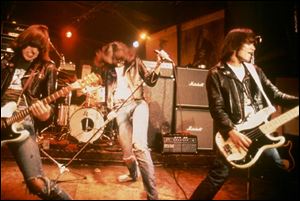

The Ramones perform in CBGB s, New York City s famous punk club, in 1977.

The final minutes of End of the Century: The Story of the Ramones (Rhino, $19.99) break your heart. The surviving members assemble at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 2002, Joey Ramone having died of lymphatic cancer in 2000. Tommy Ramone, with a gray mane, looking more hippie than punk, is gracious; he pays tribute to his late friend. But Marky just nods. Dee Dee thanks himself. And Johnny, an improbable (though bona fide) conservative, thanks George W. Bush.

Joey, the lovable nerdy string bean of a singer, and the best-known member, becomes the elephant in the room, pierced and loud, and dutifully ignored. The members stand apart from each other, and then off stage, they walk away without a word. Decades of hurt and hatred go unresolved. Two months later, Dee Dee died of an overdose. Last September, as this film was reaching theaters, Johnny died of cancer.

If you only knew these pioneering punks from Queens by their reputation, their threatening appearance, or, say, their trademark blast of guitar, now used by television to peddle everything from sports cars to cell phones, I'm jealous.

You don't bring the baggage that a fan brings. You can come to their short, tightly controlled, joyous songs about high school, romance, and beating people up - they wrote perfect pop - with fresh ears. You can take the story of the Ramones for what it is, a twisted, passionate tragedy, and not, as a fan might argue, an appreciation of a group that became a cultural line in the sand.

End of the Century, however, makes a case for both. It starts with a familiar refrain: In 1975 rock was self-indulgent, and the Ramones cleaved it in half, removing its professional, virtuosic excesses, while rediscovering the heedless abandon of the music's early roots. They also proved you could do it yourself, and when they arrived in England in 1976, thousands did. In America, the Ramones were ignored. But in London, the Clash and the Sex Pistols (to name two) saw them and were invigorated. As one fan remembers, upon hearing their debut, "It instantly made half of our record collections obsolete."

In 1975 disco was on the rise. Rock was full of remnants from its peace-and-love days. "Everything was brown," says Legs McNeil, editor of Punk Magazine. "Everything was earth tones. Everything was wheat groats."

The Ramones were like clowns among businessmen. I first heard them when I was 9, and I remember thinking it was a put-on. No one willfully played with this much speed or lack of finesse. It had to be a joke: No one that ugly would be allowed on the cover their own records.

The truth was much stranger.

The Ramones, formed in the 1970s in Forest Hills, Queens, put up a united front for three decades. They became friends over a love for Iggy Pop and the Stooges. But it's the last thing they agreed on, the filmmakers make plain. They wore black leather jackets, torn Converse sneakers, stringy T-shirts; at least two Ramones kept their hair in Moe Howard bowl cuts. Their songs contained no solos; they could race through 20 tunes in 30 minutes. Despite matching surnames, they were not related, and after 20 years and thousands of shows, they barely looked at each other - never mind spoke.

End of the Century has its Behind the Music/Spinal Tap moments: Asked why he replaced drummers so often, Johnny says, "They couldn't keep up." But I wasn't prepared for the chill filmmakers Michael Gramaglia and Jim Fields found during their years of interviewing the band and its inner circle. I first saw End of the Century at the Toronto film festival in 2003. Legalities kept it tied up. You can see why: Johnny and Joey hated each other until the end. Johnny stole Joey's girlfriend in the early 1980s and married her. In retaliation, Joey wrote "The KKK Took My Baby Away." He made it a standard at shows. Joey sang, Johnny slammed away on guitar, never betraying any emotions.

I used to think Fleetwood Mac - with its incestuous romances between members, breakdowns, drug abuse, and sacks of cash - begged for the biopic treatment. What the story lacks, however, is empathy: It's hard to care for spoiled millionaires with mediocre ambitions. Johnny Ramone, on the other hand, kept that Moe cut until his death, a decade after the band broke up. They never made much money and they folded before getting their due: Punk and hip-hop, which come directly from the DIY tradition, dominate the 21st century.

If the rock band biography is our new western - full of cliches, cozy archetypes, familiar plots retold ad infinitum, and hard to get sick of - the legend of the Ramones is like a frontier tale. The sadness is there, the hardship is evident, and the big picture is poignant. The larger point, which End of the Century leaves nicely unstated, rests in your head: The Ramones, by tossing off the '60s and pointing the way to less formal paths in pop culture, transformed culture itself. They walked among us. They rocked. They mattered.

THE LAZY BONES: After the Sunset (Warner, $27.95), directed by Brett Ratner, is an interesting movie to reach home video the same week as Mike Nichols' Closer (Columbia, $28.95) and Mike Leigh's Vera Drake (Warner, $27.98). Those last two you watch with a gulp in your throat, start to finish; they're so intense it becomes claustrophobic. After the Sunset, however, is such a slack, unnecessary heist picture with Pierce Brosnan and Salma Hayek, I was left with one question: Can't these two afford their own vacations to the Bahamas?

Even the names are lazy: Brosnan is a Max, Hayek is a Lola, and Woody Harrelson, as the FBI agent hot on their trail, is a Stan.

Of course they are.

Vera Drake is on the dark side of the moon, comparably. It stars Oscar-nominated Imelda Staunton in the title role as a lumpy, grandmotherly wife in 1950s London who cheerfully makes her rounds, helps shut-ins, cooks meals, and harbors a secret: She provides abortions at a time when the act is mired in a legal gray area. On the grim subject matter alone, and despite strong reviews, Vera Drake has had no luck finding an audience; but you'd be surprised how fair-minded and engrossing it is.

Closer is engrossing the way a 20-car pileup is engrossing. Starring Julia Roberts, Clive Owen, Natalie Portman, and Jude Law, it's acted as if the studio they're shooting were on fire. They play lovers who cheat on each other with each other, and when the gloves come off, it's so brutally honest, at one point I actually gasped out loud and then looked around to see if I had embarrassed myself. The audience was too wrapped up to even notice.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.