DEADLY ALLIANCE: WEAPONS OVER WORKERS

Brush gives victims the option to 'volunteer'

2/7/2013

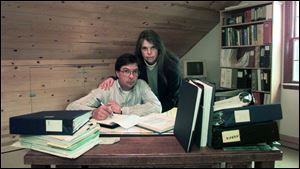

Dave and Theresa Norgard, of Manitou Beach, Mich., have criticized Brush's public service program. Mr. Norgard, a beryllium victim, has refused to participate in the program.

Two years ago, Brush Wellman applied for a top honor given by the local United Way: the Heart of Volunteerism Award.

One of the company's key claims was that it had placed several full-time employees of its Elmore plant in public service positions.

Brush Wellman ended up winning the award -- and told the media so in press releases.

But what the company didn't tell the United Way or the public was why these workers were volunteering in the first place.

They had contracted beryllium disease at the plant and did not want to further expose themselves to the toxic metal. So Brush Wellman required them to become full-time volunteers or lease themselves to other companies instead of working at the Brush plant.

If they refused, they would lose their pay.

DEADLY ALLIANCE: How government and industry chose weapons over workers

One victim is now picking up trash and cutting grass in a low-income Toledo neighborhood.

Another is counseling students in Genoa Area Schools.

Another is doing odd jobs for a shooting club at Camp Perry, an Ohio National Guard base.

"It's disgusting," says Dave Norgard, who has beryllium disease and has refused to do volunteer work. "It's a modern-day version of slave labor."

Four workers with beryllium disease, an often-fatal lung illness, are now doing public service work under this program, but some say they are being forced against their will and that Brush is using them as public relations tools.

"They're collecting awards for making people sick and then forcing them to work in jobs they don't necessarily want to do," says one of the workers, who requested anonymity.

Brush Wellman defends its program.

"We didn't do this to win an award or impress the United Way," says Dennis Habrat, Brush's director of occupational health affairs.

The program was created, he says, because an increasing number of workers were being diagnosed with beryllium disease, yet they had no visible symptoms. In the opinion of Brush and its medical director, these employees remained able to work.

But there was a problem: There was no place in the Elmore plant where victims could work without further exposure to deadly beryllium dust. Yet they were not sick enough to qualify for workers' compensation.

So Brush wanted to find them jobs as opposed to paying them for sitting home, as it had been doing in some cases for years.

What kind of alternative work they do is largely up to them, the company says. "We don't want to sentence somebody for life to some job they hate," Mr. Habrat says.

Brush officials say they know of no other company with such a program.

Victims deemed able to work have three options:

- Continue working at the plant and risk further injury.

- Quit working and receive one year's pay.

- Accept a job outside of Brush as a contract employee and continue to receive their regular Brush pay.

If workers volunteer for a nonprofit group, Brush receives nothing in return.

But if they work for another business, that company reimburses Brush the amount it would normally pay for that position. There is one such case now: A beryllium victim is doing computer work for an Elmore manufacturer.

For those too sick to work, Brush supplements their workers' compensation pay so they earn the same as they did before they became ill. This generally lasts until they retire or die.

Brush began requiring some victims to volunteer or return to work in 1995.

One victim, Mr. Norgard, a 43-year-old from Manitou Beach, Mich., refused. So he has not received a paycheck from Brush in two years, though the company says it still considers him an employee and hopes he will eventually accept a public service job.

Mr. Norgard says he has refused because Brush changed the rules on him midstream: After he was diagnosed with beryllium disease, Brush agreed to pay him even if he didn't work; now it wants him to do public service work.

Plus, he says, "I don't want to be used as a pawn so Brush can win awards."

When Brush applied for the United Way of Greater Toledo's top corporate volunteerism award in 1997, the company had to fill out a form. Brush trumpeted many of its activities, saying that 80 per cent of its employees volunteer.

Prominently mentioned was the policy that places workers in community service positions. But Brush did not say that these workers had beryllium disease and that they had been paid to volunteer, records show.

United Way spokeswoman Kim Sidwell says that when the award was given the United Way did not know Brush was using victims as volunteers. She didn't know if that information would have precluded Brush from winning.

"They are great supporters of ours, and this is an issue between the company and their employees," she says.

Many other Brush workers with beryllium disease have chosen to continue working in the Elmore plant and risk further injury.

Scientists do not know for sure if additional exposure aggravates the disease, but they have said for nearly 50 years that prudence dictates victims be removed.

Theresa Norgard, wife of Dave, the beryllium victim, says Brush has had years to find jobs within the company for sick workers.

"My God, you can't come up with a game plan in 50 years? They didn't want to do it. They didn't have to do it. So they didn't do it."