Shrinking of industry cuts 50,000 area jobs in decade

3/20/2011

The automotive industry was hard hit, including Chrysler's Toledo Assembly complex.

Metro Toledo lost 50,000 jobs in the last decade — nearly one out of every 12 jobs lost statewide since 2000 — as significant portions of the region's and state's once-mighty industrial base fled for greener pastures or closed completely.

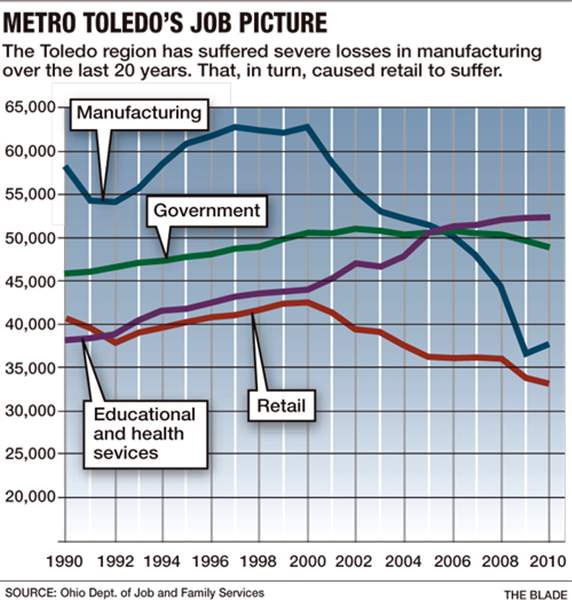

The losses in the last decade in metro Toledo, new state figures show, were widespread: 25,000 fewer manufacturing jobs; 14,000 fewer jobs in trade, transportation, and utilities; 9,500 fewer in retail, and 1,800 fewer in local public schools, colleges, and universities. Overall, metro Toledo lost 14 percent of its jobs between 2000 and 2010.

Of the job sectors tracked by the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, only educational and health services showed net gains in the last decade in metro Toledo. Eighty percent of those new jobs were in health care and social assistance.

"The Great Recession hit Toledo particularly hard as the severe correction in the auto industry resulted in a large number of jobs lost to the local economy," explained Kurt Rankin, an economist with PNC Bank. "The recession pushed the market area's already-slow demographic trends into decline."

All of Ohio's largest cities lost jobs over the decade.

Statewide, Ohio had 594,000 fewer nonfarm jobs at the end of 2010 than it did in 2000, state figures show.

Among its large metro areas, the results were grim for most: Dayton lost 15 percent, Youngstown 14 percent, Cleveland 13 percent, Akron 5 percent, and Cincinnati 4 percent.

Metro Columbus, insulated in an economy steeped in public-sector jobs, lost just 1 percent of its jobs between 2000 and 2010.

Retail operations such as Blockbuster, which is closing this store on Laskey Road near Jackman Road in Toledo, have been hurt by kiosks and online ordering.

"We lost significantly in manufacturing from 2000 to the current period, but over the last year, we've started to see manufacturing level out and even seen some gradual improvement," said Keith Ewald, chief economist with the Ohio Bureau of Labor Market Information. "Certainly, health care has been our strongest sector of our economy as a whole."

Auto manufacturing

Few sectors locally have been hit harder than automotive manufacturing, which has shed almost three of every five jobs that existed a decade ago. Job losses in the sector — one of the largest components of the region's gross metropolitan product — started with a slow leak a decade ago and ended with a deluge in 2009. Ultimately, an estimated 25,000 largely high-paying jobs vanished, and experts say most will be gone for good.

In a January analysis of Ohio's ongoing job losses over the last decade and especially since the 2007 recession, economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland said Ohio's prerecession employment levels set it up for a bigger hit in the downturn.

The report stated: In 10 of 11 major industry groups, the state's employment growth was lower than the national growth rate when compared to their most recent employment peak.

In addition, Ohio, prior to the last recession, had a much larger manufacturing share than the nation as a whole, so the state suffered more.

The remnants of those lost jobs litter metro Toledo's economic landscape:

- On North Detroit Avenue, New Mather Metals Inc. closed last year. The firm survived two World Wars and a Great Depression and employed hundreds making automotive components for Henry Ford and others before shutting its doors and terminating its final 50 employees last April.

- In Maumee, Ford Motor Co. closed its award-winning Maumee Stamping Plant in 2007, putting 1,200 out of work. Efforts to restart work there have largely failed and the building remains mostly vacant.

- In Pemberville, the former Modine Manufacturing Co. closed a plant in October, 2009, after more than three decades of making components for vehicle heating and cooling systems. Lost were 300 jobs at what was the town's largest taxpayer.

- In Lyons, DriveSol Worldwide Inc. shuttered its automotive component plant in 2007, dropping more than 160 jobs and leaving Fulton County with hundreds of thousands of dollars in infrastructure improvements that it had built four years earlier to allow the plant to expand operations.

"It goes back to the broken-window theory of urban development," explained Neil Reid, a professor of geography and planning with the University of Toledo.

"If you've got a broken window in a vacant building and then you fixed it, then no one notices. But if no one fixes it, then ultimately other windows get broken and you're left with the impression that no one cares," Mr. Reid said.

But empty buildings aren't the only monuments to local job loss over the last two decades.

Automation casualties

Some of the 50,000 jobs lost across metro Toledo in the last decade were victims of increased automation and greater productivity, allowing employers to make the same or more products with fewer workers and to raise their profits with reduced local payrolls.

For example, Chrysler employed about 5,000 workers in 2001 in Toledo, making about 270,000 copies of the last Jeep Cherokees, the first Jeep Libertys, and the Jeep Wrangler. Last year, Chrysler and its on-site suppliers employed about half that number to produce just under 240,000 Wranglers, Libertys, and Dodge Nitros.

"Ten years ago, in the paint shop at [the former Jeep] Parkway [plant], we had about 30 people spray-painting cars. Now we have one guy doing repair work, but only when he's needed," explained Bruce Baumhower, president of United Auto Workers Local 12, which represents workers at Chrysler's Toledo Assembly complex.

"And in the body shop, where we had 65 people [welding], now we have one guy who does repair work. The rest is all done by robots. That just blows me away."

"It's difficult because those are good-paying jobs that are gone from our community, but the problem is that if we don't make those advancements, somebody else will," Mr. Baumhower said.

Productivity gains also have resulted in fewer jobs at General Motors Co.'s Toledo Powertrain Plant. Today, the plant's 1,600 employees produce nearly 5,000 transmissions per day for the automaker's front and rear-wheel drive vehicles. A decade ago, Powertrain had 4,000 workers producing 8,000 transmissions per day, spokesman Wanda Wellman said.

The retail sector

The past decade was harsh on the local retail sector too. Metro Toledo lost 9,500 retail sector jobs between 2000 and 2010, state figures show, while the losses in the sector statewide were nearly 122,000 jobs.

The retail job losses have come in a variety of ways, including sweeping changes in the industry as it struggled to cope with the rise of online retailers. Kmart, for example, has closed 14 of its locations in Ohio since 2008, resulting in the loss of about 950 jobs, including its store in Perrysburg that was closed in 2009.

Self-serve kiosks, mail-order companies, and vending machines are replacing interactive human transactions in retail at a variety of locations, such as Blockbuster, which is shutting some local video rental stores.

Small retail operations like hardware stores and pharmacies also felt pressure from an increased presence of Wal-Mart, Walgreens, Lowes, Home Depot, and other big-box stores, many of which either developed or expanded their presence in metro Toledo over the last decade.

The state estimates 3,100 jobs were lost in metro Toledo at what it calls "general merchandise stores" between 2000 and 2010, compared to the 1990s when overall employment in that sector remained stable.

"If you lose jobs where people have high levels of income, which many manufacturing jobs had, then it just stands to reason that jobs in retail that rely on that income would be disappearing too," said Mike Veh, work force development manager for The Source, Lucas County's one-stop employment assistance center.

Across the state, government work declined slightly or stayed relatively stable in all metro areas except Columbus, which added 13,000 such jobs in the last decade.

Health-care field

One sector of the state and every metro area economy has been on a steady 20-year climb: health care.

"There's been a shift in the importance of health care in the U.S. economy," David N. Gans, vice president of innovation and research for the Medical Group Management Association, told the American Medical Association recently.

"We are seeing an increase in the number of physicians, and that is resulting in a need for more support staff. And these are good jobs. They are well-paid, rewarding positions. There are very good growth opportunities. You're not flipping a burger."

In Ohio, hospitals alone have added 37,400 jobs over the last decade, an increase of 19 percent from 196,200 in 2000. Nursing and residential care facilities have put on 24,000 jobs in the same period, up 17 percent from the 143,900 jobs a decade ago. Social-assistance jobs, a category that includes drug counselors and social workers, have added 26,500 positions statewide over the last decade, state and federal analysts estimate.

Metro Toledo and Youngstown were the only areas in Ohio to add fewer than 10,000 health-service jobs during the 2000s, with Toledo adding 8,700 jobs, up 20 percent, and Youngstown picking up 5,800 jobs, or 16 percent.

"The baby boomers are reaching an age where they are requiring more health care, and they're living longer. Those two things have increased health-care demand," said Wendy Papenfuss, director for work force planning for ProMedica, a Toledo-based health-care system that owns hospitals and other health care services.

"Our workers are also part of that baby-boom generation, so as we're seeing an increased demand for our services, we're being squeezed by people leaving the work force."

Health-care analysts, she said, forecast 20 percent growth in health-care jobs for probably the next two decades.

Columbus had the greatest gain of such jobs among metro areas in Ohio, adding 36,900 jobs, or 42 percent more than its 2000 total. Cleveland added 38,600 jobs, up 26 percent, Cincinnati added 27,400 jobs, up 23 percent, and Dayton added 10,700 jobs, up 18 percent.

Economist Ken Mayland of ClearView Economics in suburban Cleveland said demographics and economics play key roles in the job increases in health care.

"The older a population gets, its demand for health care doesn't go up linearly, it goes up exponentially," he said. "Health care is the kind of thing that, if your income rises 1 percent, your demand for health care goes up more than 1 percent. I guess that's because we consider our lives worth something."

Contact Larry P. Vellequette at : vellequette@theblade.com or 419-724-6091