100 years on, Rockefeller Foundation still busy

Achievement, controversy as global do-gooder the norm

5/13/2013

Members of two local cassava associations gather in Malawi, as a part of the foundation's AGRA program, which was launched in 2006 in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. AGRA is an African-based and African-led organization charged with sustainably increasing the productivity and profitability of small-scale farms throughout Africa.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Tatomkhulu-Xhosa, left, explains to Bill and Melinda Gates, right, how he has lived with and been treated for tuberculosis in recent years at the Khayelitsha Site B Clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. Bill and Melinda Gates are in South Africa to learn more about efforts to fight TB and HIV/AIDS in the country. According to the latest rankings compiled by the Foundation Center, the Rockefeller Foundation is the 16th largest, with total assets of $3.5 billion, compared to $34.6 billion for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

NEW YORK — For the richest American family of their era, the goal was fittingly ambitious: “To promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world.”

With that mission, underwritten by the vast wealth of John D. Rockefeller Sr., the Rockefeller Foundation was chartered 100 years ago in Albany, N.Y. For several decades, it was the dominant foundation in the United States, breaking precedent with its global outlook and helping pioneer a diligent, scientific approach to charity that became a model for the field.

It earned the abiding gratitude of many beneficiaries, inspired imitators and — due to its power and influence — became a periodic target of criticism from both right and left.

“They were in a very small group of foundations that practiced idea-based philanthropy as opposed to just charity. They are willing to invest in ideas,” said Bradford Smith, who as president of the New York-based Foundation Center oversees research on philanthropy worldwide.

The next generation of philanthropists would be wise to study the history of the Rockefeller Foundation and its handful of peers, Smith said.

“The new money goes about this as if there wasn’t any history,” he said. “I think there is a lot to learn — what worked, what didn’t work.”

Now dwarfed by the largesse of Bill Gates and other contemporary philanthropists, the Rockefeller Foundation remains ambitious and well-funded, and is increasingly eager to work in partnerships.

It is celebrating its centennial by touting an array of forward-looking projects, ranging from global disease surveillance to strengthening vulnerable cities’ resilience to future calamities. It is also looking back, at a 100-year history replete with triumphs and controversy.

The Rockefeller Foundation played pivotal roles in introducing Western medicine to China, developing a vaccine for yellow fever, combating malaria, establishing prestigious schools of public health, and spreading the lifesaving agricultural advances of the Green Revolution. Recipients of its grants included Albert Einstein, writer Ralph Ellison and choreographer Bill T. Jones.

Still, detractors challenged the foundation’s work. From the left, activists accused it of being a front for U.S. corporate and national security interests. From the right, critics over the years faulted its support for population-control programs and for research by Alfred Kinsey and others into human sexuality.

During the 1930s, the foundation provided some financial support to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Germany, which, among other projects, conducted research related to Nazi-backed eugenics and racial studies.

The foundation says that its grants to the institute were focused on straightforward genetic research, and that it cut off support for any projects that veered into social eugenics.

Members of two local cassava associations gather in Malawi, as a part of the foundation's AGRA program, which was launched in 2006 in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. AGRA is an African-based and African-led organization charged with sustainably increasing the productivity and profitability of small-scale farms throughout Africa.

Also during the 1930s, and continuing after the start of World War II, the foundation funded a project to relocate scholars and artists, many of them Jewish, who were losing their positions in Germany under the Nazis.

Even before the foundation was first proposed, there were sharply mixed views about John D. Rockefeller Sr. and the fortune he amassed as the founder of Standard Oil.

Rockefeller was “perhaps the most reviled as well as the most generous man in America” in the early 1900s, according to a just-published history of the Rockefeller Foundation which it commissioned to mark its centennial. The book depicts Rockefeller as America’s first billionaire, with a fortune that today would be worth $231 billion.

On the advice of his inner circle, Rockefeller sought a congressional charter for a foundation that would coordinate his already substantial charitable giving.

Some government officials were suspicious of the endeavor and some newspaper editorialists suggested the project was a cynical effort to improve the family’s checkered image. The measure proposing a charter died in the U.S. Senate, prompting the Rockefellers to turn swiftly to New York state, where lawmakers unanimously approved a charter that was signed into law on May 14, 1913.

It was one of three major, still-operating foundations founded in that era, following the Russell Sage Foundation in 1907 and the Carnegie Corporation in 1911.

Judith Rodin, who has been the Rockefeller Foundation’s president since 2005, noted in an interview that the Rockefeller family started channeling huge sums into philanthropy at a time when the tax code didn’t reward such practices.

“Clearly they were improving their own images,” Rodin said. “But they had strong views that people with that much money should give it back to society.”

She also credited the family with establishing a broad, flexible mandate for the foundation so that its leaders, over the decades, could tackle a wide array of challenges, both in the United States and worldwide.

“We have the luxury and responsibility of picking the big, thorny problems, without worrying about offending governments or our donor base,” Rodin said.

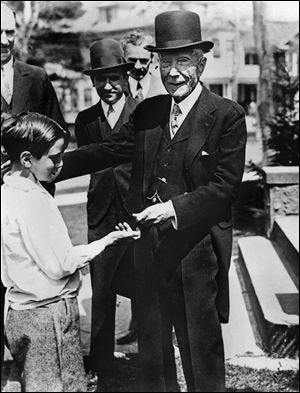

U.S. oil magnate and philantropist John D. Rockefeller gives a dime to a child. Underwritten by the vast wealth of the founder of Standard Oil, the Rockefeller Foundation was chartered in 1913 in Albany, N.Y. For several decades, it was the dominant foundation in the United States, breaking precedent with its global outlook and helping pioneer a diligent, scientific approach to charity that became a model for the field.

In a summary on its website, the foundation touts the accomplishments of past leaders and staff in taking on those problems. “Through their efforts,” it says, “plagues such as hookworm and malaria have been brought under control; food production for the hungry in many parts of the world has been increased; and minds, hearts, and spirits have been lifted by the work of foundation-assisted filmmakers, artists, writers, dancers, and composers.”

Much the creative work has taken place at the foundation’s Bellagio Center in northern Italy. Maya Angelou and Susan Sontag did some of their writing there, and novelist Michael Ondaatje worked on “The English Patient” while in residence at the center.

Among the foundation’s proudest achievements was the Green Revolution — the nickname for a series of initiatives between the 1940s and 1970s that dramatically boosted agriculture production around the world. The concepts — such as improvements in irrigation, wiser use of fertilizer and pesticides, development of high-yield grains — were pioneered by agronomist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Norman Borlaug, and then spread to other nations via Rockefeller Foundation programs.

After several decades of dominance, the Rockefeller Foundation was overtaken by the Ford Foundation as the nation’s largest.

Now, according to the latest rankings compiled by the Foundation Center, the Rockefeller Foundation is the 16th largest, with total assets of $3.5 billion, compared to $34.6 billion for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In terms of total giving, the Rockefeller Foundation ranked 39th with gifts of $132.6 million in 2011, compared to more than $3.2 billion given by the Gates Foundation.

Those financial realities have prompted the Rockefeller Foundation to do most of its current work in partnerships, rather than operating solo. Partners have included the Gates Foundation, which Rodin sees as a positive influence on the entire foundation sector.

“It’s forced us to be even more strategic than if we didn’t have it,” she said. “It’s been beneficial for other foundations — it may have catalyzed more collaboration.”

Dwight Burlingame, a professor at Indiana University’s Center on Philanthropy, said such partnerships have become crucial to effective grant-making.

“Foundations need to be more nimble,” he said. “The number of players has dramatically increased — foundations have pushed recipients of their grants into getting more partners, so it’s not a single source.”

The number of foundations in the U.S. and worldwide has surged in recent years, and a new generation of billionaires in Asia and other regions is showing increased interest in philanthropy.

Rodin says the Rockefeller Foundation, in addition to its other projects, is holding conferences for aspiring philanthropists from developing countries to provide advice on effective giving. It’s been a leading proponent of “impact investing” — investments that can spur social and environmental progress as well as earn profits.

“We’ve tried not to be out there hectoring others to become philanthropists, but to be there as a resource for those who do want to give,” she said. “We’d like to help them not make the same mistakes over and over.”

Rodin, who came to the Rockefeller Foundation after serving as the University of Pennsylvania’s first female president, has served as co-chairwoman of the NYS 2100 Commission, an expert panel formed by New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in the wake of Superstorm Sandy.

The commission’s task — to recommend ways that New York could more effectively respond to and recover from future storms — dovetails with some of the Rockefeller Foundation’s major initiatives of recent years. It has worked in New Orleans and several Asian cities to build resilience in response to super storms and man-made disasters.

Those efforts reflect the overlapping, interconnected nature of many modern-day challenges — climate change, environmental degradation, poverty and food security.

“The problems don’t land in neat packages,” Rodin said. “The problems are more complicated. The world is more networked. We need more partners.”