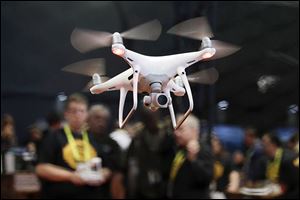

Drone fight takes to air

Firms build counter-industry aiming to stop them

2/1/2017A boom in consumer drone sales has spawned a counter-industry of start-ups aiming to stop drones flying where they shouldn’t by disabling them or knocking them out of the sky.

Dozens of start-up firms are developing techniques — from deploying birds of prey to firing gas through a bazooka — to take on unmanned aerial vehicles that are being used to smuggle drugs, drop bombs, spy on enemy lines, or buzz public spaces.

The consumer drone market is expected to be worth $5 billion by 2021, according to market researcher Tractica.

The arms race is fed in part by the slow pace of government regulation for drones.

In Australia, for example, different agencies regulate drones and counterdrone technologies. “There are potential privacy issues in operating remotely piloted aircraft, but the Civil Aviation Safety Authority’s role is restricted to safety. Privacy is not in our remit,” the safety authority said.

“There’s a bit of a fear factor here,” says Kyle Landry, an analyst at Lux Research. “The high volume of drones, plus regulations that can’t quite keep pace, equals a need for personal counter-drone technology.”

The consumer drone market is expected to be worth $5 billion by 2021, according to market researcher Tractica, with the average drone in the United States costing more than $500 and packing a range of features from high-definition cameras to built-in GPS, predicts NPD Group, a consultancy.

Australian authorities relaxed drone regulations in September, allowing anyone to fly drones weighing up to a little over four pounds without training, insurance, registration, or certification.

Elsewhere, millions of consumers can fly high-end devices — and so can drug traffickers, criminal gangs and insurgents.

Drones have been used to smuggle mobile phones, drugs, and weapons into prisons, in one case triggering a riot. One U.S. prison governor has converted a bookshelf into an impromptu display of drones his officers have confiscated.

Armed groups in Iraq, Ukraine, Syria, and Turkey are increasingly using off-the-shelf drones for reconnaissance or as improvised explosive devices, says Nic Jenzen-Jones, director of Armament Research Services, a consultancy on weapons.

This is feeding demand for increasingly advanced technology to bring down or disable unwanted drones.

At one end of the scale, the Dutch national police bought several birds of prey from a start-up called Guard From Above to pluck unwanted drones from the sky, its CEO and founder Sjoerd Hoogendoorn said.

Other approaches focus on netting drones, either via bigger drones or by guns firing a net and a parachute via compressed gas.

Some, like Germany’s DeDrone, take a less intrusive approach by using a combination of sensors — camera, acoustic, Wi-Fi signal detectors, and radio frequency scanners — to passively monitor drones within designated areas.

Newer start-ups focus on cracking the radio wireless protocols used to control a drone then take it over and block its video transmission.