Price of injury, insult awaited in mailman fraud case

5/13/2001Michael D. Smith has the chiseled physique of a bodybuilder.

At one time, he was able to dead-lift nearly 400 pounds. His “Herculean build” is so stunning that it places the middle-aged man in the upper tenth of 1 percent for people his age, a doctor once reported.

But authorities said it was Smith's physique that led them to question his claims that he was injured and couldn't work.

The former mail carrier has pleaded guilty to 15 counts of defrauding the Federal Employees Compensation Act benefits program of more than $190,000 after claiming that injuries sustained during a 1985 fall prevented him from working.

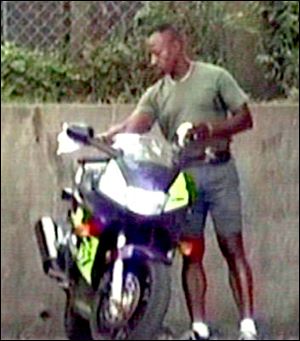

While Smith claimed he was so disabled from a 1985 fall along his postal route that he couldn't work, authorities introduced as evidence in the case surveillance videotape they said proved otherwise. Smith's sentencing hearing is tomorrow.

Tomorrow in federal district court in Toledo, U.S. Judge James Carr will decide at a sentencing hearing what Smith, now 57, will pay for a deception that dragged on nearly a decade, fooling doctors, frustrating investigators, and costing taxpayers thousands of dollars they may never recoup.

For years, Smith lamented that he was so terribly disabled by the fall along a daily mail route that he couldn't lift more than a few pounds over his head.

He said he couldn't use scissors or sort mail. He needed a daily nap.

His knee hurt. His shoulder ached. His fingers tingled. His neck popped.

In all, he collected $221,821.57 in disability benefits and $42,020.66 in medical care from 1985 to 1997 - much of the time while he was regularly lifting 300 to 400 pounds at local gyms, competing in weightlifting competitions, jogging, roller skating, and biking.

Judge Carr ruled previously that investigators had proven Smith's fraud back to 1988, putting his fraud liability at a total just over $190,000. Nevertheless, his is believed to be one of the largest postal worker compensation fraud cases in the nation last year.

Prosecutors said the case has made Smith a “poster child” for postal workers' compensation fraud.

“It's one of the worst, if not the worst, cases I've seen,” said Kim Kepling, an inspector with the U.S. Postal Inspection Service's Cleveland office. “It's not just the amount of money. It's this big discrepancy between Mike Smith on paper and Mike Smith at the gym.

“He was so bold - like he thought he'd never be caught,” Ms. Kepling said.

Smith could not be reached for comment despite several attempts by The Blade. He reportedly has moved to the Harrisburg, Pa., area.

Since its reorganization in 1971, the Postal Service has accrued $5.6 billion in workers' compensation bills and benefits that carry throughout the life expectancy of disabled workers.

By far, most claims are legitimate, but investigators get frustrated trying to prosecute those few who take advantage of the system, said Molly McMinn, spokeswoman for the U.S. Postal Inspection Service.

Naturally, doctors don't want to second-guess a patient who insists on an elusive pain; consequently, investigators find it difficult to prove the injury-linked pain is a lie, Ms. McMinn said.

“Most of our employees are very deserving. If they say they are disabled, they are,” said Michael Rae, a fellow postal inspector with Ms. Kepling. “Some of them want to come back to work, even on modified duty, sooner than they should. But then you have a Mike Smith.”

Smith's case began March 28, 1985. While delivering mail near Ottawa Park, the mail carrier slipped on a muddy lawn, he told supervisors.

Though he temporarily returned days later to light duty, Smith walked out again in August complaining of pain linked to the incident.

Requesting full disability and using documents from his doctor, Smith would receive 75 percent of his regular pay, or about $1,334 every four weeks. Under the benefits program, he would pay no federal taxes on the money.

Soon after, claims personnel would hear of periodic “sightings” of Smith engaged in strenuous activity.

But Smith's doctors - contacted by the post office's injury compensation clerks - continued to report they were treating him for various aches and pains.

“Keep in mind, that the doctors are trusting that the employee is being open and honest with them,” said Lou Kerekgyarto, the injury compensation specialist assigned to Smith's case.

“The doctors were not the problem,” Mr. Kerekgyarto said. “Michael was the problem. He was calling the shots.”

Not only did Smith insist on aches and pains and numbness, he denied that there was light duty work available to him when doctors asked. He had begun to lift weights, but lied too about that, investigators said.

In 1990, Dr. Glenn Carlson, an orthopedic surgeon treating Smith, pressed his purportedly disabled patient about his remarkable physique.

Smith answered that it “was inherited because ... he didn't have to work on it to look good,” the doctor said.

In fact, Smith told Dr. Carlson “just with routine daily living not requiring work he was having a difficult time.” The patient insisted that he was exhausted by noon.

But already, Smith had been pumping iron, eventually meeting up with a local high school teacher. The two worked out five to six days a week, two hours a day. On Mondays and Thursdays, they lifted weights to develop their chests and biceps, the teacher later told investigators.

On Tuesday and Friday, they'd work on their backs and trapeziuses. On Wednesdays and Saturdays, they hit the leg routines.

“On Smith's `bad' days, he would squat 225 pounds,” court records attribute the teacher as saying.

Back at the injury compensation office, Mr. Kerekgyarto, who for 17 years had been a letter carrier, was assigned Smith's case.

Each year, the injury compensation office handles dozens of legitimate injury claims from postal employees in a district that stretches from the Indiana and Michigan lines to Sandusky and Findlay. The paperwork can be staggering even in real injury cases.

“It takes an overwhelming amount of evidence to get a claim overturned,” Mr. Kerekgyarto said. “Just seeing someone out is not going to change doctors' minds. And you never know, they may have just had a good day.”

The case went into overdrive in November, 1994. During a Christmas shopping trip with his family at Franklin Park Mall, Mr. Kerekgyarto spotted Mr. Smith in the food court chatting with friends.

The physique of the mail carrier who was so disabled he couldn't lift a mail bag was shocking. Even under the leather he wore, it was obvious that Smith's arms, torso, and legs were “like an Olympic athlete,” Mr. Kerekgyarto recalled.

“What struck me,” he said, “was the contrast in the way he appeared there and the way he appeared on paper.”

Nearly a decade after Smith's mishap near Ottawa Park, the post office insisted he return to work. He did July 10, but left two weeks later for a scheduled knee surgery.

He returned again Oct. 3, 1995 - for one hour and 24 minutes. The cement, he complained, aggravated his knee. Sorting mail irritated his shoulder.

Smith returned on Nov. 1 to answer phones and clip address labels, but left again less than three months later - this time for stress. A doctor soon afterward wrote that Smith could not “bend or twist, nor can he lift more than 20 pounds.”

On paper, Smith was almost completely debilitated.

In the gym, a different picture of Smith was developing - literally.

There, undercover investigators used surveillance tapes to record the extraordinary weightlifting that Smith later said was “therapy” for his injuries. Interviews with a former girlfriend and former exercise partners confirmed that Smith had been busy during his sick leave - driving on long trips, playing beach volleyball, bicycling, and jogging.

There were doctor appointments and disability paperwork in between.

A friend once asked Smith if he ever got tired of all the requirements he had to fulfill for his disability payments, according to court records. “Yes,” Smith reportedly replied. “I work hard not to work.”

In July, 1997, the post office notified Smith his benefits were terminated. Eight months later, he was fired.

Smith's attorney, Jon Richardson, still argues that physical therapy had been prescribed by Smith's doctors, although he concedes “the court found the extent to which Mike rehabbed himself was beyond what could be defended as medically necessary.”

“As counterintuitive as it sounds you can lift a lot of weight in a short time, but not a little weight over a long period of time,” Mr. Richardson told The Blade.

Smith's hearing tomorrow is scheduled for 10:30 a.m., and those who worked so closely on his case say they will be there.

Mr. Kerekgyarto says he owes it in part, to all those postal workers who are legitimately hurt on the job and those who do their jobs without complaint. Those people, he said are “true heroes.”

“I think of those people who are out there every day, trudging through the snow, dealing with dogs, and they're working so hard,” he said. “I don't want to be overzealous, but this is a clear case where we did the right thing.”