Deceased ex-Marine wins final campaign

11/18/2003

I was elated. I wept a little, says Jean Quinlan, widow of Marine Sgt. Richard Quinlan, with the Purple Heart that was awarded to her husband. Mr. Quinlan was wounded at the Battle of Guadalcanal.

fraser / blade

The waiting is over for the wife of Marine Sgt. Richard Quinlan.

Almost 61 years after being wounded in battle and two months after he died in Toledo, the old soldier has been awarded a Purple Heart.

“I was elated,” his widow, Jean, said of her reaction after getting the award Friday. “I wept a little.”

Mr. Quinlan s war wound occurred during a Japanese bombing attack during the World War II Battle of Guadalcanal. It was during the attack that Mr. Quinlan recalled bleeding from a head wound after diving for cover. The wound healed on its own, and he forgot about it for almost six decades.

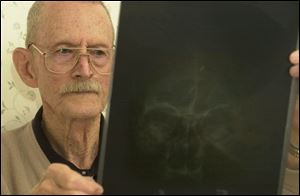

Then, two years ago during a medical exam, the Medical College of Ohio staff were stunned to find a piece of shrapnel lodged in Mr. Quinlan s skull. It was then that Mr. Quinlan s battle to get his medal started.

Over those two years, he and his wife wrote letters to military officials and others in hopes of receiving the Purple Heart, a military decoration given to soldiers injured or killed in combat. It was a race against time, and at several steps along the way, they ran into bureaucratic roadblocks:

Richard Quinlan had a head wound.

They wrote to the Navy and were told the Navy didn t handle such requests and forwarded the letter to the Marines. Ten months went by. They sent another letter, this time to the Marines. Six months went by, then the Navy replied - turns out the Navy was the right place to start - and said Mr. Quinlan didn t qualify because he needed two witness statements, not one.

Angry at not being told that in the first place, but determined to press on, Mrs. Quinlan began calling old Marines who had served with her husband. By this time, her husband was too frail to continue his effort. After crossing off about 20 names, she finally reached an aging veteran who agreed to vouch for Mr. Quinlan. That man s letter was sent in July.

Mr. Quinlan, 81, died a month later, without his medal.

At first, Mrs. Quinlan didn t want to keep fighting for the medal, but decided to try again. From her South Toledo home, she called the Navy again and was told it never received the second witness letter. She faxed another copy, and on Friday the medal arrived, with a letter:

This responds to your recent inquiry, concerning a Purple Heart for your husband, the late Mr. Richard Quinlan, for his service in the U.S. Marine Corps. I regret the delay in receiving your husband s records and responding to your inquiry. As verified by the eyewitness statements ... it has been determined that your husband is entitled to a Purple Heart posthumously for wounds received in action against the enemy on Nov. 24, 1942, on Guadalcanal.

“It took so much to get it accomplished, but I m so glad I stayed with it,” Mrs. Quinlan said.

Mr. Quinlan had wanted the medal to give to his grandson. After Mrs. Quinlan keeps it a while, she said it will be placed in a shadow box with her husband s other medals and handed down to the grandson, who lives in Adrian.

Mr. Quinlan spoke to The Blade in November, 2001, about the unusual discovery of the shrapnel in his skull. He said he had landed on Guadalcanal on Nov. 11, 1942. It may have been Armistice Day, but there was little if any peace to be found on the island.

“I walked right into living hell,” he said. “I thought my first day in a combat zone would be the last.”

Then 20, he was one of the first group of Marines trained to make maps from aerial photographs. Their job was essential because of the precise maps the military needed for the “island hopping” strategy.

While Mr. Quinlan had always insisted if he never got the medal, it was no big deal, his wife and daughter said that really wasn t the case.

“He was a modest man. He wouldn t have wanted a big fuss being made over it,” said his daughter, Kathleen Nelson, who lives in a St. Louis suburb. “[But] part of it was it took so long, that the longer it took the more he felt he wasn t going to get it, so he kind of justified [his indifference] that way.”