Newsman Pyle of WW II fame had Toledo link

4/18/2005

Ernie Pyle's last visit to Toledo, in 1941, included a visit to Willys-Overland, where workers turned out artillery shells, tank treads, and parts for anti-aircraft guns as well as Jeeps.

blade

Ernie Pyle, the famed and beloved World War II correspondent, died 60 years ago today.

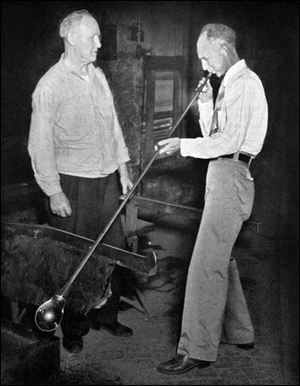

Ernie Pyle, visiting Toledo in August of 1941, tries his hand at blowing glass under the guidance of Libbey master craftsman Aaron Bloom. The columnist died 60 years ago today.

He was mourned by many Toledoans who had met him in his earlier assignment - when he was a "roving reporter" during the Great Depression and up until a few months after the United States entered World War II in December, 1941.

Mr. Pyle seemed to like visiting and writing about Toledo, which he dubbed a "rough-and-ready city," and he wrote a number of columns about Toledo, its factories and workers, its shipping docks and tugboats, its restaurants, and its prized Toledo Museum of Art.

For years, his folksy columns were syndicated by the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain and appeared in dozens of papers around the country, including the former Toledo News-Bee, a Scripps-Howard publication until it folded in 1938, and after that, in The Blade six days a week.

In Toledo, his columns were titled "Roving Reporter," but they went by different names around the country, such as "Hoosier Vagabond" at some papers in Indiana, where he grew up as a farm boy.

His audience grew, especially after he took time out from his U.S. travels to cover the air raids during the Battle of Britain in late 1940 and early 1941. During World War II some 200 newspapers carried his dispatches from the front, which earned a 1944 Pulitzer Prize for distinguished correspondence.

He was killed April 18, 1945, by a Japanese machine gunner on the tiny island of Ie Shima, off the coast of Japan, in the closing months of World War II. He was four months short of his 45th birthday. President Harry Truman called him "the spokesman of the ordinary American in arms," and the United Press news service report of his death called him "a peaceful little guy who became this war's greatest correspondent."

Mr. Pyle was admired for his "common touch," a straightforward, earnest writing style that had a way of turning ordinary events and ordinary people into something approaching poetry. It was in cities like Toledo where he honed the people and writing skills that earned him praise in the war.

Ernie Pyle's last visit to Toledo, in 1941, included a visit to Willys-Overland, where workers turned out artillery shells, tank treads, and parts for anti-aircraft guns as well as Jeeps.

Many of his dispatches read like letters to folks back at home, just as his earlier columns were aimed at average Americans.

For example, he enjoyed a tugboat ride up and down the Maumee River during his first visit here, in the spring of 1937. "We went steaming up the Maumee, riding like millionaires," he wrote in his popular column. He noted that whenever the captain blew a whistle, the bridges opened.

"It gives a fellow the Napoleon complex to be sitting there in the pilot house of a little old tugboat and looking up at all the autos lined up on the bridge waiting for us to get past, and all we're doing is taking a joy-ride. It's enough to make communists out of people."

Although Mr. Pyle wrote mostly about the workaday, gritty side of Toledo, he also dabbled a bit in culture.

After visiting the art museum, he wrote: "You might as well get this straight I'm not in the habit of browsing around art museums." But he warmed up to it, and allowed as how "one of the things I'll do when I become a millionaire [is] come to Toledo and find out what art is all about."

Four months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Mr. Pyle came to Toledo, intending to stay just a day or so, but he ended up staying a week.

He wrote about glassmaking with a sense of wide-eyed wonder.

He was intrigued by "the glassmaking capital of America," especially some of the city's remaining "old-time craftsmen before the furnaces, blowing and twirling and shaping molten glass into freehand pieces of art, very much as it has been done for centuries.

"Glassmaking is one of the most fascinating things I've ever watched, because right before your eyes you see a miracle. Just think, if you yourself were to take a wheelbarrow load of sand, lime, and ash - really nothing but a load of dirt, you see. Then you heat it to 2,600 degrees, and it gets fluid, about like molasses. And then, when you let it cool, instead of turning back to dirt again, as it should, it comes out clear and clean and brittle, like glass. My gosh, it IS glass!"

He described his own attempt to blow a piece of glass at Libbey Glass, then a division of Owens-Illinois Inc. (Libbey Inc. is now a separate public company): "I was nervous as a cat [but] first thing I knew I was getting the feel of it. It was such a wonderful sensation of accomplishment that I lost all my bashfulness and just blew brazenly until my eyes stuck out."

Mr. Pyle also was fascinated by Libbey's machines that turned out millions of tumblers. He watched workers inspect for imperfections and destroy the defective glasses.

(Libbey no longer makes handblown vases or art glass at its North Toledo facility, a spokesman said. However, years ago, the firm memorialized Mr. Pyle's columns about Toledo glassmaking in a small book, Ernie Pyle on Glass, which is available at the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library.)

During that last visit to Toledo, in 1941, Mr. Pyle also stopped by the sprawling Willys-Overland factory, which was gearing up for the war by making Jeep vehicles (it turned out about 360,000 of them before the war was over).

In his column, he told the nation that the gigantic factory also was making huge artillery shells, tank treads, and components for antiaircraft guns - part of the defense effort that shut down passenger-car production.

Probably Mr. Pyle's most famous column from Toledo, written in 1937, reported on his getting "the bum's rush" at a once-bustling restaurant, Bud and Luke's.

"The whole business (and a very prosperous business it is, too) has been built up on the policy of insulting customers," he wrote. And this was decades before Jerry Seinfeld's "Soup Nazi" segments on television.

According to Mr. Pyle's account, he apparently didn't order fast enough and was ejected by waiters. "Whisshhh - there I was right on the sidewalk, thrown out of the place!" Later, when he actually had a meal there, waiters had slipped silverware into his topcoat.

"When we started to leave, I could hardly lift my topcoat from the rack," he related. "Waiters came running from everywhere. They felt in the pockets and yelled, 'We've caught a thief! We've caught a thief!'

"They took out enough knives and forks to set up the whole restaurant. They took out salt and pepper shakers, and jars of sugar, and bottles of catsup Everybody in the place was howling."

The day Mr. Pyle died, The Blade reported that "Ernie Pyle numbered a lot of Toledo residents among his thousands of friends."

And a day later, an editorial noted: "His talent was for writing in a common vein of common men and common things for the common people, who wanted to know what their relatives and friends in the fighting areas were doing - what they ate, how they slept and awakened, what they did in their pitifully brief leisure moments."

Contact Homer Brickey at: homerbrickey@theblade.com or 419-724-6129.