1st use of the atomic bomb divides Americans

7/31/2005

George Taoka helped interrogate prisoners in Hiroshima, including his brother-in-law, who had survived the bombing.

king / blade

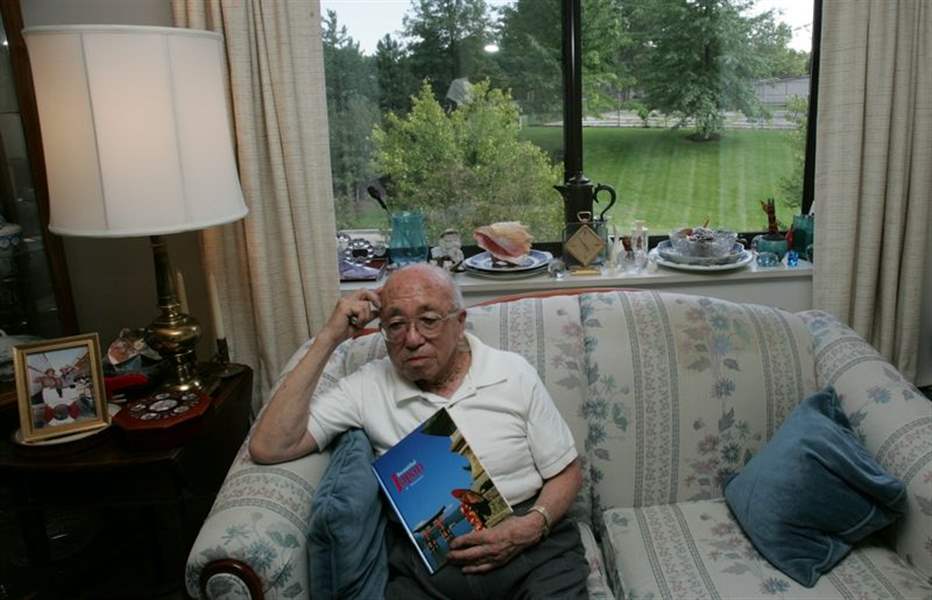

Retired art teacher Arthur Koskinen, 87, of Perrysburg fought in World War II.

Arthur Koskinen remembers exactly where he was 60 years ago when he learned that America had dropped the first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

He remembers the canvas tents at the camp on Guam and the men of the 3rd Marine Division - men he had fought alongside during the bloody battle for Iwo Jima months earlier - huddled around their radios and the thoughts that flashed through his head when President Harry Truman announced the news.

"It was a two-fold feeling," the 87-year-old Marine veteran and retired art teacher from Perrysburg recalled of that moment in World War II. "You knew the war was going to be over now, but you couldn't help thinking about the people who were on the receiving end of it. War is horrible anyhow."

Mr. Koskinen was among thousands of Toledo-area residents who helped shape the events that led to victory over Japan in the Pacific in early August, 1945, and the end of World War II.

Among them were research scientists trained at local colleges who helped design the atomic bomb; battle-scarred combat veterans like those of the 37th Army Division mobilized from the Ohio National Guard; workers who churned out more than $3 billion in Jeeps, munitions, and other war supplies at area factories, and average citizens who bought war bonds and rationed gasoline and other items.

As the 60th anniversary of the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima approaches this week, however, fewer and fewer of those who have been called members of what has been coined as America's Greatest Generation are left. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, more than 1,100 of the nation's World War II veterans are dying each day.

"It's important that we commemorate this [60th] anniversary," said Richard Baranowski, a local historian with Way Public Library in Perrysburg who has been collecting oral testimony and photographs from people who experienced the war first-hand. "At the 70th anniversary, how many people will still be around?"

The personal, first-hand memories that breathe life into arid historical accounts are fading away. Some still remain, frail but vibrant like Milton Bracht, 84, who, as a 23-year-old private in the Army, worked on the top-secret program to develop a nuclear weapon known as the Manhattan Project.

Based at Oak Ridge, Tenn., one of the three sites that brought together top scientists from around the world, Mr. Bracht played a small role in the $2 billion project.

He used his electrical engineering degree from Toledo University to help develop the fuel for the bomb by operating a sensitive measuring device known as a mass spectrometer.

Despite hastily built laboratories that occasionally gave way underfoot, Mr. Bracht and his colleagues worked their instruments 24 hours a day.

"What with the circumstances of the war, we had to get done quickly," he said.

And they did. By May, 1945, the first atomic bombs were ready for deployment.

President Truman authorized dropping the bomb nicknamed "Little Boy" over the Japanese city of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. More than 70,000 people were killed, and the world suddenly entered the nuclear age.

George Taoka helped interrogate prisoners in Hiroshima, including his brother-in-law, who had survived the bombing.

Three days later, a second bomb known as "Fat Man" was dropped over the city of Nagasaki with similar results: Nearly 40,000 people were killed or injured and one-third of the city was destroyed. On Aug. 14, 1945, Japan announced its surrender; the formal surrender documents were signed on Sept. 2 aboard the USS Missouri.

For many World War II veterans, the atomic bomb was a necessary evil, one which saved hundreds of thousands of American and Japanese lives - lives that would have been lost had the American military been forced to invade the heavily defended Japanese mainland.

"It was war," said Don Cleese, 79, a semiretired advertising manager from Perrysburg, who manned a turret gun aboard a B-29 bomber and flew 39 missions in the South Pacific between January and August, 1945. "Truman had to do it, and he did the right thing."

Over the years, however, academics have been more critical of the decision to use the bombs.

William Hoover, a professor of Japanese history at the University of Toledo, said the usual balance drawn between the cost of an American invasion and the damage inflicted by the bomb is an unfair one.

"By August, 1945, Japan was surrounded," he said. "Her air and sea power was virtually knocked out, as were her transport and manufacturing systems. So there was no necessity to invade."

Pressure by conventional means could have resolved the war, Mr. Hoover said.

But Mr. Cleese said he has little time for suggestions from people who were not involved with fighting the war.

"The people who criticize really don't know the story," he said. " I feel bad that so many people had to die, but [President Truman and the military] had to do it. We didn't start the war."

George Taoka, a Japanese-American, was placed in an internment camp at Heart Mountain, Wyo., at the start of the war but later served as a military intelligence officer in the South Pacific.

For Mr. Taoka, who is retired after a long career as an economics professor at the University of Toledo, the meaning of the atomic bomb is far more ambiguous.

Five months after the attacks, Mr. Taoka arrived in Hiroshima to interrogate a Japanese suspect.

He was surprised to discover the detainee was his brother-in-law but even more shocked by the utter devastation of the once bustling city - a city that he had known as a young student visiting relatives in April, 1941.

"The city was absolutely flat," the 89-year-old resident of the Swan Creek Retirement Center in Toledo recalled. "It was incredible."

The only building left standing in Hiroshima was the Industrial Promotion Hall, which Mr. Taoka had visited in 1941.

The devastation took a personal toll also: Two relatives exposed to the bomb's fallout died later from radiation sickness.

"Hindsight is pretty good," he said, "but if the war could have been ended some other way, it would have been better."

Contact Jeremy Lemer at: jlemer@theblade.com or 419-724-6050.