Schools waking up to student breakfasts

3/12/2006

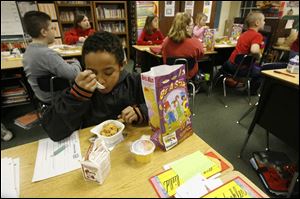

Tyler Piercefield, 10, chows down on his cereal at Liberty Center, which just started its breakfast program this month. Tyler's breakfast bag included milk, juice, and crackers.

McKayla Knapp is the epitome of the reason elementary schools serve breakfast.

The 10-year-old gets up at 4:30 a.m. and watches television - waking up slowly - while her parents get ready for work. She's too sleepy then to be hungry for breakfast.

Shortly after 6 a.m., the family is out the door, dropping McKayla off at a babysitter's home. There, she has some crackers and orange juice packed from home. Then she walks from the babysitter's to school, where lunch - her first full meal of the day - is served at 11:30 a.m.

By that time - seven hours after she woke up - she's been hungry for a while.

No more.

This month her school, Liberty Center Elementary in northeastern Henry County, started selling breakfast for students to eat in their classrooms.

This year is the 40th anniversary of the federal school breakfast program, which was part of the federal Child Nutrition Act of 1966 and came 20 years after the federal government started subsidizing school lunches.

Still, three times as many school lunches are served nationwide as school breakfasts. Dietitians often quibble over the nutritional content of the menus that schools offer for both. But few knock studies saying children who eat breakfast do better in their morning classes.

Yet, in Ohio, only about 65 percent of the state's school districts offer breakfast, even though state and federal subsidies - along with prices charged to pupils - often make the service self-supporting.

State taxpayers give school districts 6 cents for every breakfast served. The far bigger subsidies are from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which provides $1.27 per breakfast for children who qualify for free lunches, 97 cents for those who qualify for reduced price, and 23 cents for those who pay full price.

At Liberty Center, administrators decided to serve breakfast when their federal Agriculture Department grant for fresh fruit and vegetable snacks ended in December.

That program provided broccoli, cauliflower, celery, carrots, strawberries, grapes, and even edible orchids at no cost to every student in kindergarten through fourth grade.

The fruit and vegetable program continues with a $9 million appropriation for the year starting Oct. 1. But Liberty Center wasn't one of the 225 schools chosen nationwide to share in it this year.

So some elementary classes, many of which had the fruits and vegetables in the morning, went back to a schedule of parents sending in class snacks.

The fruit-and-vegetable program left its mark, however.

When one honest child, looking at refreshments brought by a classmate, asked, "When are we going to have a good snack?" Principal Margy Brennan Krueger thought he probably preferred a different type of cookie. What the boy wanted, though, was a return to the carrots and grapes from the agriculture program.

The first month of the school's breakfast menu, which is similar to many others in the area, might be more similar to snacks from busy parents than the fresh fruit-and-vegetable program.

It includes milk - with a choice of 2 percent, skim, or chocolate - every day and juice almost every day. On three days out of the month, the menu has a piece of fruit such as an apple or banana instead of juice.

The other two items, of what is typically a four-item meal, are often cereal, crackers, or pastry. A cheese cube is offered several days. One day, there will be a sausage link with chocolate chip pancakes.

Such proteins look good to Deb Horner, a dietitian with Mercy Children's Hospital.

Foods with lots of fiber - such as a piece of fruit or whole grains such as oatmeal - are digested more slowly and give kids energy throughout the morning.

"Juice and cereal don't get that," she said.

But she knows, she said, why they dominate school breakfast menus, which seldom thrill her. Juice has a much longer shelf life than fruit, which helps to make it less expensive, and pastries have wide appeal in cafeterias where some children are quick to throw away anything they aren't sure they like.

Indeed, Liberty Center's breakfast menu looked pretty good to 9-year-old Ashley Reed.

"Some people don't like broccoli," she said, politely alluding to her distaste for some of the produce that had been offered to her under the agriculture program.

On March 1, the first day breakfast was available, about two-thirds of the students picked up a sack with cereal, milk, crackers, and juice that was priced at 80 cents and was free to those who qualified for free or reduced-price lunches.

That should be an improvement because almost any food children eat for breakfast is better than eating nothing or only a little bit, Ms. Horner, the dietitian, said.

And McKayla, who typically consumed only juice and crackers during her long morning, was getting a lot more morning nutrition than some of her classmates who tried the school breakfast last week.

Paige Chamberlain said she is so tired when she gets up at

6:25 a.m. to catch a 7 a.m. bus to school that there's no way she's hungry for breakfast at home. Sometimes, she said, she even falls asleep on the bus.

Contact Jane Schmucker at: jschmucker@theblade.com or 419-337-7780.