Suburban schools fall short on diversity

4/1/2007

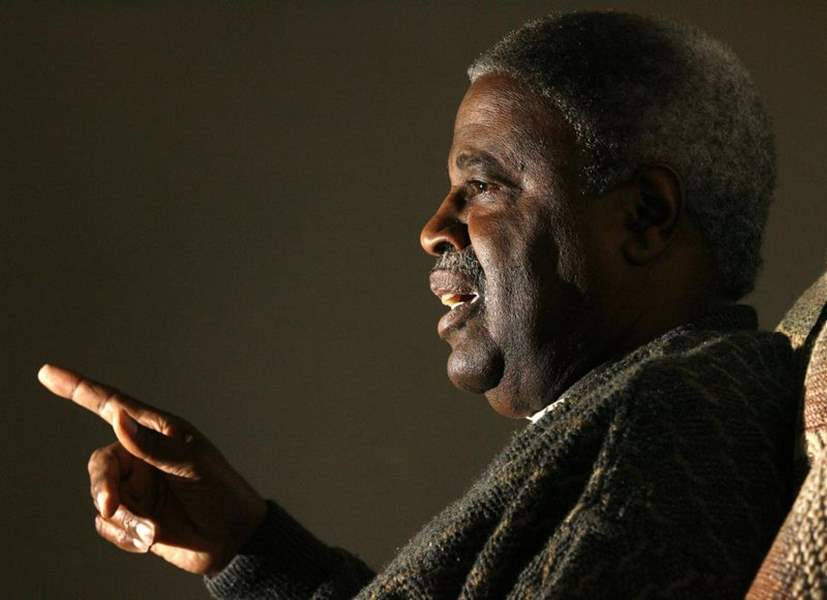

Selma Rankins, a retired teacher in Monroe County schools, said his students are better citizens today because they learned valuable lessons of diversity at an early age.

Jeremy Wadsworth

Selma Rankins, a retired teacher in Monroe County schools, said his students are better citizens today because they learned valuable lessons of diversity at an early age.

TEMPERANCE It was unusual when the slightly gray-haired man walked to the microphone. Not many African-Americans come to school board meetings in Bedford, let alone speak to the board.

Selma Rankins knew his presence was remarkable.

I know you must be wondering what I want, he began.

But that was precisely why he had come. He hopes that one day the presence of African-Americans in the school district will be more common.

His question: Why are there no African-American teachers in Bedford Public Schools?

Mr. Rankins, 64, was one of the few African-American teachers in Monroe County, Michigan, during his 33 years in the district. And he said his students are better citizens today because they were exposed to diversity at an early age.

He stressed that the valuable lesson of racial equality, like most lessons, is more easily learned while young.

You need to give them the opportunity to have teachers that don t look like them, Mr. Rankins said. My students didn t have a problem adjusting. One black teacher can make such a difference in kids lives.

Suburban students in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan do not experience the same levels of diversity as children in large urban districts, according to a survey by The Blade.

Predominantly white suburbs are nothing new. Since they became an American institution in the 1950s, suburbs have been a product of white middle-class flight from urban centers, in large part to create communities where tax dollars could support better public services mainly schools.

Mr. Rankins was 11 in 1954, when the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown vs. Board of Education laid the groundwork for better racial integration in public schools across the country.

Bedford school board member Michael Smith, a 1992 Bedford alumnus, said it took time to adjust to diversity in college.

He graduated from high school in Monroe, La., in 1961, but schools in Louisiana were not integrated until 1968. After high school, he went to Grambling State University, a historically black university in Louisiana, because other universities in the state were still segregated.

Integration was a slow process, and it still is, he said.

In 1954, Oliver Brown, the plaintiff in the historic court decision, was fighting the To-peka school board in Kansas for making his daughter, Linda, attend her segregated black school instead of her neighborhood school the all-white Sumner Elementary.

Instead of walking down the block with the other children each morning, Linda was forced to walk six blocks to her school bus stop and then ride for a mile to attend third grade at Monroe Elementary, in Kansas, now designated a National Historic Site.

A long way to go

In front of the Bedford school board, Mr. Rankins referenced this history and acknowledged the strides that have been made, but he expressed his dismay that more has not been accomplished in the last half century.

This is not 1954. We ve come a long way, but we have a long way to go, he said. This is a changing world. The world is getting smaller every day, and we need to prepare these kids.

Bedford school board member Michael Smith said he only had white teachers growing up and it was poor preparation for college.

I was like a duck out of water, Mr. Smith, a 1992 Bedford alumnus, recalled from when he first arrived on the campus. It took time to get used to learning from teachers who did not look like me.

Bedford High School assistant principal Rhonda Gant has endured racial threats since becoming the district s first African-American administrator in 2000.

A widespread issue

School districts such as Bedford, which have only white, full-time teachers on their staffs, are common in the Toledo area. Mason, Ida, and Summerfield school districts near the Michigan and Ohio border, and Maumee, Rossford, Eastwood, Napoleon, Bryan, Wauseon, Northwood, and Tiffin school districts in Ohio, to name a few, have only white, full-time teachers, The Blade review shows.

That represents roughly 30,000 students who will have only white teachers by the time they leave school.

Other area districts have one African-American or Hispanic teacher in the elementary or middle school but have only white teachers at the high school level. Sylvania, Perrysburg, Bowling Green, Otsego, and Defiance fall in that category.

That means 20,000 students will have only white teachers in high school.

And while the Ottawa Hills, Anthony Wayne, Lake, and Port Clinton school districts have between one and three Hispanic teachers in their districts, they have no African-American teachers, according to Ohio Department of Education statistics for the 2005-06 school year.

All told, that is about 60,000 students who will not have any African-American teachers before they go to college or venture into the global workplace.

There are many of those who will have only white teachers all through school because they may not be placed in the one or two elementary classes or the few high school classes that are the exception to the rule.

Spreading the word

Mr. Rankins has been going to school board meetings throughout southeast Michigan and northwest Ohio to make board members aware of the problem and to get them thinking about solutions.

After Mr. Rankins speech at Bedford, board member Robert Zahn said it was one of the most interesting and thought-provoking meetings he ever attended.

What guts it took to come up and do that to speak in front of this sea of Wonder Bread, he said.

While most school officials agree that having a diverse teacher population would better educate their students, they say it is not easy finding and recruiting minority candidates.

But I pledge we will try to do better, said Wes Berger, Bedford s assistant superintendent of human resources. Sometimes, when you are so consumed by the everyday problems that you have in the district, you tend to forget what is important.

Suburbs not alone

Disparities in teacher diversity are clear in cities such as Monroe and Toledo, where school districts lead their counties in student-body diversity.

While Toledo Public Schools student body has more African-American students than white students, only 11 percent of its teachers are black.

I would say, like any school district, it is not where we would like it to be. But we do put in a lot of effort to hire and recruit [a diverse faculty], said Donald Haddox, Jr., Toledo Public Schools director of human resources.

The Monroe Public school system has twice the number of African-American students as the county average, but only 2 percent of its teachers are African-American, compared to 9 percent of its student body.

There are several schools in Toledo and Monroe that have no minority faculty members.

Recruiting efforts

Mr. Haddox said he is part of a minority recruitment consortium that discusses recruitment strategies among 660 district officials statewide.

The state consortium has discussed pooling its resources so that one representative body could recruit minority candidates at historically black universities across the nation and entice them to Ohio.

He said competition is fierce, and some districts are now hiring minority teaching students during their sophomore year of college and agreeing to pay for their senior year as an added incentive.

But in Michigan the operation of such a consortium has become an open question.

In November, Michigan voters approved Proposition 2, which has amended the state constitution to provide that public universities, colleges, and school districts may not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.

The Michigan Department of Civil Rights maintains that outreach to hire minority teachers does not violate the constitutional amendment.

We believe that while Proposition 2 eliminates preferential treatment, that does not include outreach to organizations that may pertain to persons of color, as long as that outreach isn t solely to those organizations, said Harold Core, the department spokesman. Outreach has always been the main way to encourage diversity, attending teaching fairs at predominantly black universities and communicating with minority organizations. We believe that is still permissible, as long as you are not just outreaching to those institutions.

Terry Serbin, Monroe s assistant superintendent of personnel, said he relies on teacher fairs to find minority candidates because he cannot ask candidates to list their race on job applications.

It started so we couldn t rule out minorities, but now it s having the opposite effect, he said.

So in order to find diverse faculty, many districts send representatives to teacher fairs, where they can see the race of potential candidates firsthand.

Consuelo Hernandez recently took the post of human resource director for Sylvania Schools.

From April 16-20, she will join recruiters from across Michigan and Ohio who are looking for qualified teacher candidates.

Obviously one of my big goals is to make the school more diverse, she said. But we can t sit back and let them come to us. We need to reach out to them and find ways to make [minority] candidates feel more comfortable.

Challenges of change

Ms. Hernandez said she believes showing a commitment to diversity is the first step.

Attitude is a big part of it, showing that we are committed, that we are welcoming, she said. As professionals, you want to feel supported.

Rhonda Gant agrees. She is an assistant principal at Bedford High School, and in 2000 she became the district s first African-American administrator.

You are not going to set yourself up to go through a lot of the challenges I have had to go through over the last seven years if you feel the community doesn t want you there, she said.

Because of racist threats by students and community members, Bedford High School s only two security cameras currently are pointed at her office s front and back doors.

She went to court in 2003 over what she describes as a racially harassing and intimidating e-mail sent by a student. Then in 2004, she received two other written threats. One of them stated, I am going to kill Rhonda Gant on October 18th.

Monroe County sheriff s Deputy Randy Krupp, one of the district s two liaison officers, has moved his office next to hers for extra protection.

But I m not going to let anyone drive me out, she said. When you are a change agent anywhere, you will encounter a large amount of resistance.

Layne Hunt Monroe Public Schools first African-American principal resigned the post in 2004 after only three years on the job.

Monroe specifically was a school that was experiencing some challenges in the area of diversity, and I was asked by the district to serve as principal of the high school to address some of the concerns, Mr. Hunt said. And during my time there, I began to address some of the inequitable treatment of the minority students and began to try to encourage mutual respect of parents who were coming to the building who were African-American or Hispanic.

He said he left in part because of conflicts with the administration and community that stemmed from trying to tackle some of the sensitive racial issues.

There are some problems being a minority in a majority situation, he said. If you take a Caucasian majority person and put them in a minority situation and ask them to work like they would in their comfort zone ... it s difficult.

Mr. Hunt, principal of Ypsilanti High School, suggested districts set up workshops to support minorities both socially and academically and provide them with a place where they can talk openly about these issues.

Monroe High School Assistant Principal Denise Lilly said it is important to bring not only racial diversity, but also socioeconomic and cultural awareness to the schools. She is one of the district s two African-American administrators and is the co-chairman for the district s diversity committee.

It is about truly acknowledging the schools staff is not diverse enough. It is about having the conversation, instead of not wanting to have an uncomfortable conversation, Ms. Lilly said.

A view to the future

Monroe High School senior Brianna Mendez, 17, said there is something missing in the schools today.

Sometimes, if there s no one else like you, you just feel a little left out because sometimes it s easier to relate to someone that comes from where you come from. They can relate to you, she said.

Mr. Rankins, who retired as an elementary school gym teacher in 2003, said he always liked sports because the same rules apply to every player.

In real life, you have different rules for different folks, he said.

Basketball was always his game.

I can still get out there and play. I can shoot the free throw, the long shot, he is quick to add.

But he acknowledges that he is not quite the player he once was. He hopes that today s students will get the last shot in.

I ve been telling these kids, We still have problems today and it s going to be you that s going to solve the problems of this country, Mr. Rankins said.

I hope that 50 years from now people will look back and they won t believe the amount of segregation that we had in our schools today.

Contact Benjamin Alexander-Bloch at: babloch@theblade.comor 419-724-6168.