Toledo physician has mission to repatriate World War II relics

7/2/2007

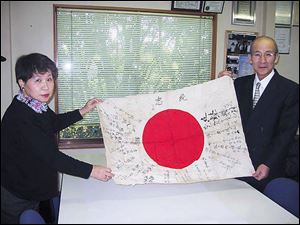

Dr. Yasuhiko Kaji displays a Japanese flag from World War II.

The Blade/Lori King

Buy This Image

As Dr. Yasuhiko Kaji shuffled through the boxes of flags, senninbari, diaries, and pictures that he has collected over the past 30 years, he came across a lushly illustrated Japanese flag.

The Buddhist goddess Kannon sat midway up the right side, her features inked into the fabric with the strong black strokes of a sophisticated artist. Daruma rolled across the bottom and up the left side of the flag. Daruma was a sage, explained Dr. Kaji, who meditated for seven years (or nine, according to some) while his legs atrophied, withered, and fell off. His rolling image means that a person can roll seven times, but will get up on the eighth.

Dr. Kaji, a retired physician who moved to Toledo as an obstetrics and gynecology intern in 1968, has sent this flag's photograph twice to the government of Japan.

The government still has a department for war victims, but it has yet to find the soldier who owned this flag - or his family.

Dr. Kaji, 73, amassed his entire collection of Japanese artifacts from World War II in the hopes of returning the long-lost artifacts to the original owners or their families.

Machiko Ohkawa, a sister of Mr. Tokumoto, who died in the Philippines, and Kenji Tokumoto, the only son of the flag s owner.

He began his slow endeavor when a friend of his wife wanted to return a worn, stained Japanese album from World War II to the family of the soldier to whom it belonged.

Without any experience in the art of object return, Dr. Kaji sent the album directly to his hometown newspaper in Nagoya, Japan. After a bit of work and luck, the newspaper found the family of the soldier. After returning the album, he found a Japanese military sword at an estate sale and bought it immediately, hoping to return it as well. He also discovered a senninbari, a wide piece of cloth worn around the waist by a Japanese soldier. Senninbari means "thousand-person-stitches;" the 1,000 stitches are each placed by a different person.

Dr. Kaji, a native of Japan who grew up there during War War II, remembers his grandmother going from house to house, asking people to stitch.

"When they go to war, they have it so that they feel protected," he said.

World War II aviator Frank Dresslar brought home from the war a signed Japanese flag that eventually was returned to the family of Yoshio Tokumoto, its wartime owner, through the help of Dr. Kaji.

Although a senninbari is an extremely personal gift from a soldier's family, they are unsigned. It is impossible to identify the soldier who carried one. Most of the artifacts that Dr. Kaji has managed to return have been flags. Called "nisshoki," or, more colloquially, "hata," the flags are usually signed by family members and friends with messages like "Long live," or "Please take care of yourself. Come back alive." Most soldiers would carry a signed flag in a pocket, close to their bodies.

Even when the flag has a name, it can be difficult to trace because 5 million to 7 million Japanese soldiers were drafted and the ministry will sometimes find six or seven soldiers with the same name. Sometimes Dr. Kaji can give the ministry information about where the flag was obtained, but most of the time he does not know.

The soldiers themselves are not usually alive to accept the flags.

"These days, if someone knows, it is inherited," he said.

Although the ministry does the best it can with the photographs that Dr. Kaji sends, he recently began to use the Internet as a second avenue, along with help from a high school classmate, Kiyoshi Nishiha. Visitors to the Web site can send Mr. Nishiha a photograph and a description of a World War II item that they would like to return to the soldier or his family.

Dr. Yasuhiko Kaji hopes the swords, above, he has collected will go to an institution that will cherish and respect them.

Because the Web site requires the chance convergence of the party with the artifact and the party who wants the artifact back, it is an uncertain means. The Web site's flags, helmets, swords, notebooks, and photographs read like a catalogue chronicling only tiny snippets of the anonymous soldiers' lives, but those snippets can become invaluable to families who manage to reclaim them.

Barbara Dresslar, of Sonora, Calif., had planned to write a family history with her father, Frank Dresslar, when she visited him at his home in Mexico, but she ended up writing his war memoirs instead. Sifting through boxes of his old belongings from his time flying C-47 and C-46 transports for the U.S. during World War II, she came across an old, signed Japanese flag.

She lived in Japan briefly, so she realized the flag probably had some personal significance.

After searching for information online, she located Dr. Kaji and became the first person to reach him directly about a flag to return.

Dr. Kaji sent a photograph of the flag to the ministry. After 30 years of receiving his mail, the staff at the ministry knows his name and pays close attention to his photographs.

A year passed before Dr. Kaji was able to tell Ms. Dresslar the ministry had just located the family of Yoshio Tokumoto, a soldier who died in the Philippines.

His only son, Kenji Tokumoto, had been raised believing his grandfather was his real father. So when the Dresslars returned the flag, they were told that it became the only tangible link he had to his real father.

Through a translator, Yoshio Tokumoto's sister, Machiko Ohkawa, sent her thanks to Ms. Dresslar.

"The time of 62 years has past since our family had got nothing which could be called as his relic or proof of Yoshio's death. Kenji could also have such wonderful an opportunity this time to know about his own father and to feel his warmth," she wrote.

Now, Ms. Dresslar has almost weekly contact with Yoshio Tokumoto's family. "I think there is still a lot of healing to be done between the two countries," she said.

Dr. Kaji said that while the Japanese government tried to return soldiers' belongings to their families early in the war, in the chaos that ensued often all that was sent to the families of fallen soldiers was a piece of paper in a box saying where the soldier died, and occasionally a small stone from the area.

Dr. Kaji lost his own father in the tense atmosphere before the war. The father became ill while stationed in China.

"They tell me I visited him, but I don't remember," he said.

His grandmother raised him until she died when he was 12. Then he moved in with his mother, who had remarried.

He was too young to serve in the military but remembers the atmosphere during World War II.

"When you're a child, you don't have much fear," he said. "Nobody cried. It was all routine. If a bomb hit you, you'd be dead."

Although Dr. Kaji has returned about 5 swords, 30 flags, and 20 notebooks, he still has 20-25 flags and more than 100 swords and other artifacts.

Ms. Dresslar hopes that modern correspondence will, at the very least, make it more possible for artifacts to be returned. "It's too bad that 62 years had to pass, but this wouldn't have been possible without the Internet," she said.

While Dr. Kaji diligently sends pictures to the ministry and to Mr. Nishiha's Web site, www.rose.sannet.ne.jp/nishiha/iryuhin/english.htm, he knows that many of the belongings will remain unclaimed.

Dr. Kaji keeps the collection in the hopes that one day, he will be able to give the artifacts to an institution that will cherish and respect them.

"I don't want them to be used for politics, one way or the other."

While individuals in Japan desperately want the belongings of soldiers from their families, the country and its institutions have a harder time accepting any artifacts that recall war and violence. But, Dr. Kaji remains hopeful.

"I am still hoping that some door will open up for them," he said.

Contact Ali Seitz at:

aseitz@theblade.com

or 419-724-6050.