Plan to raze 1884 village hall debated in Edgerton

2/18/2008

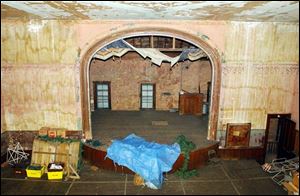

An opera hall on the second floor of the village building once hosted stage performances. It now stores Christmas decorations.

An opera hall on the second floor of the village building once hosted stage performances. It now stores Christmas decorations.

EDGERTON, Ohio - A cramped and outdated building that should be torn down?

Or a central part of the village landscape and heritage?

Edgerton officials have decided their 124-year-old village hall is the former.

This month, village council members voted 3-3, with the mayor casting the tie-breaking vote, to take bids to demolish the structure.

Village administrator Dale Mathys said the building is cramped.

"There's not enough space now - in the fire department, the police department, and the village hall," Mr. Mathys said.

The 1884 village hall was built in the heyday of Romanesque architecture. Town hall-opera house combos were common.

But some Edgerton residents say the structure - which has an opera hall on the second floor - impacts the landscape, heritage, and the very heart of their community and should be saved.

The village, about 70 miles west of Toledo in southwestern Williams County, has a population of about 2,000.

Hundreds signed a petition last year to save the edifice, preservation advocates point out. Located at U.S. 6 and State Rt. 49, the two main arteries through the village, the hall is the very heart of Edgerton, they say.

"We have something that is unique - that has not yet been destroyed," said Rita Sechlerone. "We need to keep it."

Others say the building has inherent worth because of the civic history it represents. Mary Juarez said her father and aunt told her stories about high school graduations, dances, plays, movies, and basketball games on the opera hall's wooden floor.

"There's such a beautiful history with it," Ms. Juarez said. "If we don't preserve it now, it will be lost forever."

The upstairs opera hall also was known as the Park Opera House, and in addition to community activities, it hosted stage performances.

An ornate column graces the opera hall. Estimates for restoration and for razing and building new are both $2.5 million.

On a wall inside the former ticket booth, names of dozens of performers, and the dates they were there, remain inscribed.

"Prof. Wise Chalk Talk, Sept. 19-02," reads one. "Chicago Dramatic Co., Nov. 12, 1903," reads another.

The opera house portion of the building hasn't been used in decades, however.

Its ceiling is stained from water damage and the paint is peeling. The unheated space houses the village's Christmas lights and decorations.

Still, the delicate painted stenciling that borders the room is mostly visible, as is the rural scene painted on the ceiling. The balcony is intact. High glass windows are covered with wood shutters.

"It doesn't look like much," said Darwin Krill, who with his wife, Shirley, has been leading the drive to save the building. "But if you can just image it restored "

The first floor of the building has been remodeled. Its interior bears no trace of the structure's history. Large oak staircases are hidden behind a new facade.

The building was built in 1884 in the Romanesque style, according to the Ohio Historic Inventory.

The 1880s were the heyday of this style of architecture, popularized by Boston architect H.H. Richardson, said Tom Wolf, public education manager with the Ohio Historical Society.

In that era, it was not uncommon for small communities to build combination town hall/opera houses, Mr. Wolf said. Several dozen remaining in Ohio are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Woodward Opera House in Knox County, Bell's Opera House in Highland County, and the Hayesville Opera House in Ashland County.

William Condee, professor of theater at Ohio University, said many of the buildings arose between 1870 and the end of the century because of a number of cultural and economic factors.

First, a rise in transportation made it easier for shows to travel by rail, said Mr. Condee, author of Coal and Culture: Opera Houses in Appalachia.

"Secondly, it was a golden age of popular entertainment - minstrel shows, vaudeville shows ... people were thronging to theaters to see those things," Mr. Condee said. The popularity of opera houses was fueled, too, by strong economic growth after the Civil War.

The Edgerton hall, with its village offices on the first floor and opera house on the second floor, was a common model, he said.

Though referred to as "opera houses," few of the buildings actually were used for much opera, Mr. Condee said.

They generally were called opera houses because at the time, theater was considered somewhat morally suspect. In contrast, "the opera house is something legitimate," he explained.

"If you call it an opera house, that means, its highfalutin, it's high culture," Mr. Condee said.

Like the Edgerton hall, in addition to theater performance, many opera houses hosted community events such as lectures, parties, Sunday school classes, and roller-skating, Mr. Condee said.

"It was like a modern-day community center or recreation center," he said. And they existed in many, many small towns, as key as the city hall, jail, school, or firehouse.

"Most towns in America would have had an opera house," he said. "It was a way of saying, 'This town values culture.'•"

For his part, Mr. Condee, said, his interest in the buildings is not in the architecture, but in what they symbolize.

"Many of these are buildings that are not outstanding architecturally - though many are beautiful," he said. "But the importance lies in the fact that in a small town, this is the one place where everybody can gather - men, women, rich, poor, blacks, and whites would be coming. And you can see that in the fact that it's in a town hall."

Mr. Condee added, "The importance of preserving this heritage is it can provide the same kind of opportunities in the 21st century as it did in the 19th - it can provide a place for the community to come together."

Today, many of the buildings have been torn down or turned into office space or apartments, Mr. Condee said. Surviving town/opera halls tend to be in economically depressed areas - where there was no incentive for demolition. Many are in southern Ohio, West Virginia, western Pennsylvania, and eastern Kentucky.

Mr. Condee said he knows of one in southern Ohio used as a furniture store, and another used to store auto parts.

Historic or not, Edgerton's council has voted to replace the structure and it must go, said Mr. Mathys, who has been the village administrator, on and off, for more than two decades.

"It's unusable for us," he said.

The replacement building will house the police, emergency medical service, and fire departments, along with the utilities department, all of which are cramped now.

Lack of space leads to inefficiencies, he said, explaining, "It takes longer to do your job."

The police department has no room for interrogations, he added.

"Officers don't have enough space to do their jobs," Mr. Mathys said. "They have to use each others' desks."

Council chambers can't accommodate many people either, he said.

Additionally, the proposed new building would include a large basement that could be used for storage and as a tornado shelter, he said.

He predicted the village will take demolition bids later this year.

In the meantime, officials are trying to obtain state and federal funds to help pay for the $2.5 million project.

According to a 2007 presentation by Bowling Green-based Poggemeyer Design Group, demolishing the structure to build a new hall and preserving and adding on to the existing hall would cost about the same.

Part of the cost of restoration comes from years of neglect, Mr. Mathys said.

"It sat up there for 50 years and nobody wanted to use it," he said.

There was talk of restoring the upstairs in the 1980s and 1990s, he said, but the money just wasn't there.

"Sentiment is expensive," he said.

Mayor Lance Bowsher, who broke this winter's tie in favor of demolition, could not be reached for comment.

Council President Greg Jennings, who voted in favor of the demolition, said he thought with the information he had, it was the best choice. He declined to comment further.

Mr. Mathys said now that council has voted after months of debate, he wants people to come together and get behind the project.

"The longer we draw this out, the more it costs our citizens," he said.

Opinion in the village seems to be fairly split.

"Keep it," said Vickie Apt, a lifelong Edgerton resident employed at the local supermarket. "It's the only thing we have left."

Karl Mavis, who owns Windmill Antiques just a stone's throw from the village hall, said a restored building might help bring people into the village.

But down the street at Frager's Barber Shop, owner Phil Frager said tearing the building down is "a no-brainer."

"You can build bigger and for less money and it would be cheaper to maintain," Mr. Frager said.

He said he believes a "silent majority" of residents agree with his position.

Despite the demolition vote, the Krills and others have vowed to fight on.

"It's not over until the fat lady sings," said Patricia Strouse, a supporter of saving the hall.

"And I hope she's singing in the opera house."

Contact Kate Giammarise at:

kgiammarise@theblade.com

or 419-724-6133.