Amid civil rights turmoil, Scott High chose its first black football queen 51 years ago

9/28/2008

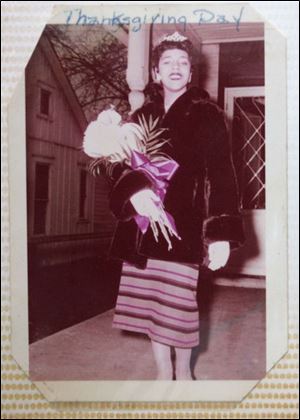

Janet Quinn-Wyatt sports a replacement crown. The original from 1957 is lost.

The Blade/Lori King

Buy This Image

Janet Quinn, Scott High s fi rst black queen, is surrounded by her court, from left, Doris Simmerell, LaGora Bey, Cherry Wright, Carol Kledis, Roberta Parkman, and Joan Brown.

Seventeen-year-old Janet Quinn wasn't about to be scared away from her coronation as queen of the Scott High School Thanksgiving Day football game.

Not even when a man called her and warned, 'If you get on that stage, you'll be sorry.'

It was November, 1957 two months after President Dwight D. Eisenhower had ordered the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock to ensure the safety of nine African-American students as they entered segregated Central High School.

That same year, Congress passed the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction.

It was against that backdrop of racial tension that Janet 'Jenny' Quinn made local and national news by becoming Scott's first black football queen.

She's also been called the first in Ohio, and the first at a large, integrated high school in the United States.

Now a 68-year-old widow living in Toledo's central city, Ms. Quinn-Wyatt will wear a tiara again when she participates in homecoming festivities Friday and Saturday at Scott, where her great-niece, Mariah Harris, is a senior.

The word 'spunky' comes to mind when one meets her. The pretty teenager has grown into an attractive grandmother who speaks in a strong voice and laughs infectiously. This is a woman who went to college at the age of 45 and stood on her head as a birthday tradition until she was 52.

Janet Quinn-Wyatt sports a replacement crown. The original from 1957 is lost.

And spunky she must have been as a high school senior.

When the caller threatened her, she remembers, 'I said, I guess I'll have to be sorry because I'm going to get on that stage.'?'

Richard Langstaff, then Scott's principal, took the matter more seriously.

'He said there would be plainclothes detectives all around,' Ms. Quinn-Wyatt said.

Shock and worry

The coronation was at the State Theater on Nov. 27, 1957. The trouble had started the week before.

As was Scott's tradition, seniors voted for a queen for the Scott-Waite High School football game and dance that were held on Thanksgiving Day, major school events that today would be called homecoming. Janet was chosen over two white girls, Cherry Wright and Carol Kledis, who would be her attendants.

African-American girls had been attendants on several occasions, but Janet was the first to be voted queen in the history of the school, which opened in September, 1913.

'The black students were very shrewd. They put all their votes on Janet Quinn, and the white students split their vote,' recalled Bob Carson of Sylvania, who was at the time a social studies teacher at Scott. He remembers Janet as 'a beautiful girl, a real nice girl.'

Ms. Quinn-Wyatt said she was shocked by the results. 'I wasn't expecting to be queen. I expected to be an attendant.'

She also was worried not because she expected anyone to protest her election but because being queen meant she would have to give a speech.

Other students initially gave her no reason to think it might be controversial. 'They were hugging me and kissing me and saying, We never had a black queen before,' and they were just thrilled,' she said.

That was on Monday.

On Tuesday, rumors began to bubble, some of them from inside the school and some in the community: Another election would be held for homecoming queen, the football players would refuse to play if the first vote was thrown out, the majorettes would refuse to march, the Scott band was going on strike, the coronation would be boycotted, there would be a fight between black and white students.

A photo from Janet Quinn- Wyatt s scrapbook shows her in November, 1957, as the first black football queen at Scott High School, after a tumultuous week at the Toledo school.

I was just numb'

Scott's student population at the time was more racially and ethnically diverse than it is today, reflecting the makeup of the surrounding neighborhood, said Tom Williams of Sylvania, a member of the Scott class of 1959. 'There was a large Jewish community, Catholics and Protestants, blacks and whites and a sprinkling of Muslims, and a couple kids from Japan,' he explained.

Both black and Jewish students had served as student body presidents, he recalled. 'You just didn't think too much about it.'

Still, 'In the '40s and '50s there were a lot of southern families, both black and white, who came north to work in the factories,' Mr. Williams noted. 'There were a number of students at that high school who were white, whose parents had lived in the South, so you still had that undertone of racism in those families.'

Ms. Quinn-Wyatt remembers kids from other high schools driving around Scott, sniffing for trouble. School doors were locked as a precaution.

According to an article in The Blade on Nov. 16, 1957, Mr. Langstaff thought the tension was starting to ease by the end of classes on Tuesday.

But on Wednesday morning, 'we came back and right on the front lawn was a huge tree, and hanging on it was an effigy,' Ms. Quinn-Wyatt said. 'It had a white sheet over it and a brown football head with a crown on it, and it was just swaying back and forth.

'I didn't cry. I don't know why. I think I was just numb.'

Five white senior boys had hung the effigy overnight. Two of them reportedly realized when they arrived at school that 'their act had touched off a crisis of sorts, so they fled in fear and were truant for the day,' The Blade reported.

Students milled around, some gathered in groups, some refused to go to class that morning. The principal described an angry 'buzz-buzz' in their voices. 'It was explosive, no question about that,' he was quoted as saying.

In his morning announcements over the PA system, he told them he had faith that the students would do what was right. A junior who gave the daily student message told them that 'the spirit of God lives in all our hearts, whatever may be our creed or color.'

Teachers led classroom discussions about the situation. Students went to the principal and asked him to do something to defuse the tension.

Mr. Langstaff decided to call an afternoon assembly of juniors and seniors where anyone could step forward and make a statement.

The emotional meeting lasted about an hour and included tearful apologies and pleas for peace from both black and white students. The two girls who were runners-up in the voting 'said they would be proud to be my attendants, and they wanted me to go ahead and be queen. Everybody was crying. It was really touching,' Ms. Quinn-Wyatt said.

Working out the issues'

Mr. Carson, the social studies teacher, described Principal Langstaff as a 'brilliant guy, a very quiet, soft-spoken man. ... He brought the group together and let them interact in the auditorium. The kids were really working out the issues themselves.'

Mr. Carson who said he thinks there is only one other surviving Scott faculty member from the 1957-58 school year wasn't at the assembly but was impressed by its results. 'I admire the daylights out of the kids. They were so mature. They did a great job themselves in handling the thing,' which he said was started by a small group and aggravated by outside forces.

'Teenagers and faculty were living an experience that the whole nation was trying to deal with at the time,' Mr. Carson said. He later became Scott's dean of boys before moving to the Toledo Public Schools' administration building. He retired in 1986 as executive director of pupil personnel and services.

'I think all of us who went through that experience are better people for it, but it was a terrible, tension-producing situation,' he said.

A legacy'

Ms. Quinn-Wyatt went to business school after she graduated from Scott, married

Harry D. Wyatt when she was 20, and raised two daughters, Bridget Hanson of Toledo (a 2008 Jefferson Award finalist for her work as executive director of the nonprofit neighborhood organization House of Adonis) and Kelly Dee Wyatt of Kissimmee, Fla.

She retired in 2004 as a Head Start teacher.

Over the years, she didn't talk much about the incident. 'I'm just now starting to mention it,' she said, explaining, 'It just seems like a legacy, and I should tell people.'

It came up a couple of times in the intervening years, once when a man she didn't recognize stopped her at the University of Toledo and asked, 'Weren't you the first black queen at Scott?'

And again at her 25th high school class reunion.

A male classmate approached and asked if she'd step out into the hall with him for a moment. He told her he was the one who had instigated the hanging of the effigy and that he had promised himself that if he ever saw her again, he would apologize.

'He thought it would be like a joke,' she said. 'He never realized he could have started a whole riot in the city. ... I told him it all turned out well, and that history was made at Scott and you were part of it.' ...

'I'm not going to tell you who it was.'

Contact Ann Weber at: aweber@theblade.com or 419-724-6126.