COMMENTARY

On both sides of the gun, violence takes a tragic toll

The young people shooting up our streets didn’t invent violence

7/14/2013

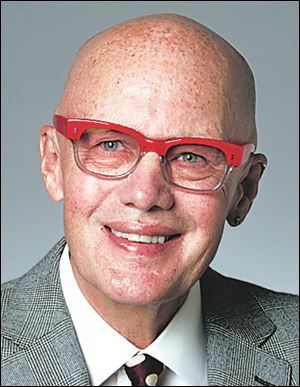

Jeff Gerritt.

A jury of seven women and five men this month convicted Keshawn Jennings, 21, and Antwaine Jones, 19, of aggravated murder and other charges. They face up to life in prison without parole. These two young men — who, undoubtedly, during some moments in their brief lives had shown at least a shred of promise and potential — have now thrown it all away.

Violence doesn’t get much more senseless than this: Someone looking for a rival gang member shoots up the wrong house, killing a 1-year-old and seriously wounding her 2-year-old sister.

No human beings were more innocent — more undeserving of their fate — than Keondra and Leondra Hooks. Last Aug. 9, they were asleep on a comforter when bullets sprayed through the glass doors of a Moody Manor apartment.

Jennings and Jones, members of the Manor Boyz gang, had gone out to “take care of business” after they learned a member of a rival Crips gang was on their turf. On the street, handling your business all too often means retaliating with extreme force, sometimes for a perceived slight, a gesture of disrespect, or an incidental intrusion on a block another gang has claimed for itself.

“Grimmin,” just looking at someone the wrong way, can get you killed.

Last year, I asked former Detroit police chief Ralph Godbee what surprised him most about his job. “The petty stuff people get killed for,” he said without pause. His officers had recently arrested a man who shot to death a driver who accidentally bumped his car while trying to maneuver out of a parking space.

But there’s a flip side to these tragedies, on the other side of the gun, that most people don’t talk about.

I don’t know Jones or Jennings, but I’ve known many men who have committed similar crimes, or played a part in them. Two decades of writing about prisons, the criminal justice system, urban issues, and the streets — mostly in Detroit — have taught me that talented, smart, basically decent, and certainly salvageable young men with no direction and a lot of negative influences can do some bad things.

Many have told me a positive male role model, or even a decent job or something positive to do, would have made a difference. By then, however, it was too late. We live in an unforgiving society that has, over the past four decades, quadrupled its prison population and become the world’s leading incarcerator by locking people up for a long time.

Many never get a second chance. That’s why I’m gratified that James Moore, 21, who drove the getaway vehicle for Jones and Jennings, will have an opportunity to turn his life around. He apologized to the family for his part in the crime, pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter, and was sentenced to three years in prison.

Too many of these young men have been African-American. People in this country have become inured and indifferent to the parade of young black men going to prison, just as they’ve ignored the racial and class biases in the criminal justice system.

Perhaps one in three young black men is under the supervision of the criminal justice system — either in prison or jail or on parole or probation. In areas of concentrated poverty, the statistics are even more grim.

My brother-in-law once told me that every one of his peers growing up on Detroit’s east side went to jail or prison. Ohio’s prison system reflects an appalling national norm: More than 45 percent of its 50,000 prisoners are African American.

None of us is blameless.

Violence, as H. Rap Brown once said, is as American as apple pie. The young people shooting up our streets didn’t invent it. We’ve celebrated guns and, through popular culture, OGs such as Lucky Luciano and Al Capone and, more recently, modern gangsters such as TV’s Tony Soprano and real life mob boss John Gotti. Killers all.

Through our indifference and neglect, our central cities have become places of little hope and less opportunity, with schools that resemble prisons and sidewalks lurking with danger. Violence is a public health problem — it’s a disease; and like most other health problems, it correlates closely with poverty.

Whenever I’ve spoken at a public school in Detroit, the nation’s poorest big city, I’ve asked students how many of them know someone who has been murdered. How many have a close relative who has been shot? How many have had a parent in prison? Inevitably, almost every hand goes up.

Given what these kids face daily, it’s a miracle most of them do as well as they do. Millions of young people in this country are surrounded by violence, not only in the media but also in their homes and on their streets. It shouldn’t shock us that a few of them become killers.

Jones and Jennings could get life in prison, but that won’t stop other young men who feel invincible from committing acts that are just as senseless. Maybe nothing would have stopped Jones and Jennings, but most troubled young people can change direction.

Violence is a community problem. Young people — who are the most affected — and ex-offenders who have changed their lives but still understand the streets need to take a lead role in Toledo’s efforts to reduce violence.

The most effective programs I’ve seen, in Detroit and elsewhere, are those that involve young people working with other young people, and with adults who understand them, their culture, and their problems. Many adults not only don’t understand these kids — they are afraid of them.

It’s encouraging that Toledo’s Community Initiative to Reduce Violence is, right now, trying to figure out ways to reach and engage young people, including those who are causing trouble.

“We can arrest people, but until we change the dynamics of the street, we’re going to continue to have this problem,’’ Sgt. Anita Madison, the community initiative’s program manager, told me. “We need to establish a two-way conversation with this population.”

All of us need to get our hands dirty and teach by example.

Nearly 10 years ago, I was waiting for a friend outside a store in a parking lot on Detroit’s east side. A young man, slumped in his car a few yards away, started grimmin, or staring me down. I glanced away a couple of times and then got tired of it. I glared back, and it was on. Our eyes locked for maybe two minutes, but it seemed like two hours.

Finally, he looked away, and I wondered why I had played this stupid game. He was young, but what was my excuse? A mindless macho duel like that could have turned deadly.

Instead of contributing to this stupidity, I should have walked over and asked him why he was wasting his time, and risking a potentially violent confrontation, staring down someone he doesn’t even know.

Maybe our leaders should declare a holiday from violence — a day when nobody would hit a child or throw up an obscene gesture at another driver, a day when we reach out to a young man who’s staring us down. People need to think about how they can intervene and influence those around them.

The culture of violence is killing more of us than any foreign enemy. There’s a war going on right here, and every senseless casualty — on both sides of the gun — reminds us that we’re losing.

Jeff Gerritt is deputy editorial page editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com or 419-724-6467. Follow him on twitter@jeffgerritt