Michigan law sparks moral debate

3/30/2014

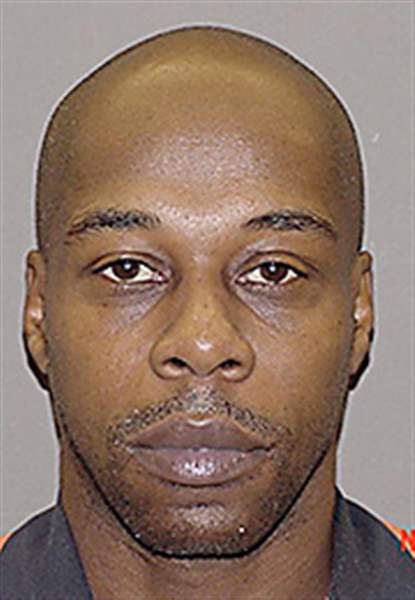

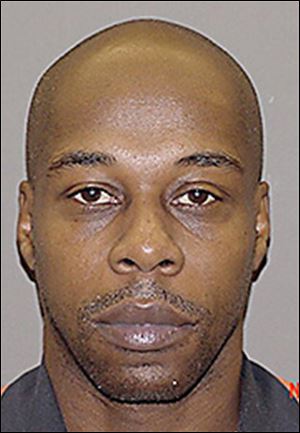

Hill

Gerritt

Michigan's barbaric juvenile lifer law — and the lawsuit involving Michigan prisoner Henry Hill — has shamed and disgraced our northern neighbor. Last week, Human Rights Watch declared that the practice of sentencing children to life in prison without parole “violates international norms and treaties.”

At the center of this struggle is my friend Henry Hill, Jr., one of the hundreds of inmates I came to know while writing about prison issues for the Detroit Free Press. Now 50, Hill was given a mandatory life sentence when he was 16 for his part in a shootout that ended with a death. Hill didn’t pull the trigger, but he was there, in the mix, and thus swept up in a conspiracy charge that gave him the same sentence as the shooter.

Crime hasn’t created the prison nation. Insidious policies such as juvenile lifer laws — Ohio doesn’t have one — have done that. Starting in the 1980s, we sent more and more people to prison for longer and longer periods. We thought we could arrest our way out of a drug problem, and we practically gave up on the notion that people, including kids, could change.

Hill

Today, with more than 2 million people locked up, the United States holds one in four of the planet’s prisoners. One in 100 Americans are in prison, but that figure doesn’t start to show the impact of mass incarceration on the nation’s poorest central cities, where prison has become almost an expectation for many young men.

Prisons now cost states more than $80 billion a year. Ohio alone spends $1.5 billion a year on prisons. Michigan spends $2 billion — more than it spends on higher education.

But the prison problem isn’t only economic — it’s moral. We’ve thrown away the keys on a significant share of our population, disproportionately poor and African-American. People are afraid, angry, or just don’t care. It’s easy to write off an entire group of people when you don’t know any of them, and many of the people who write our laws, own our businesses, and create our policies don’t know anyone who has done time.

I’d like you to know Henry Hill, Michigan prisoner No. 169371. His short criminal record has defined his life, but it tells you little about who he is.

Hill grew up in a poor family in Saginaw. Before he went to prison, a court-ordered psychological evaluation called him mentally deficient, insecure, and unable to tell right from wrong. He had the education of a typical third-grader, and the mental maturity of a 9-year-old. He was, he told me a few years ago, “as dumb as a box of rocks.”

Yet in Michigan, Hill was judged by adult standards and, when convicted, given the maximum adult penalty, even though an off-duty sheriff’s deputy testified that Hill was running from the scene when his cousin, Larnell Johnson, shot and killed Anthony Thomas during a fight at a Saginaw park in the summer of 1980.

Hill had a gun, but none of his bullets matched those in the victim’s body. Still, he received the same sentence as the shooter’s: mandatory life.

Hill is a far different person today. Articulate and well-read, he earned a GED in prison and continues to read and study. He mentors other prisoners, especially young guys. In a stark prison ceremony, he recently married a beautiful woman named Valerie.

An evaluation by the Michigan Department of Corrections called Hill cooperative, polite, articulate, and straightforward, with logical, flexible, and goal-oriented thinking.

Last year, the U.S Supreme Court struck down mandatory life sentences for juveniles. But Michigan’s ambitious and bloodless attorney general, Bill Schuette, continues to argue that the ruling should not apply to past cases, such as Hill’s.

This year, the Michigan Parole Board rejected Hill without even an interview.

In a phone conversation from prison last week, Hill told me that he wasn’t bitter. God, he said, would eventually free him to work with young people.

Hill knows he has to be held accountable, but he has already spent more than 30 years in prison. If Mr. Schuette gets his way, he will die there.

Repealing Michigan’s juvenile lifer law would not, in itself, release Hill or any other prisoner. The State Parole Board could still reject their bid for freedom if it believed any of them still posed a threat.

Henry Hill, and the more than 300 other juvenile lifers in Michigan, deserve that chance.

I’ve visited all of Michigan’s more than 30 prisons, except for one, as a journalist, speaker and volunteer, and as a family member visiting my brother-in-law. Those experiences have shaped my views of prisons and the people in them, just as having gay children has helped shaped the views of Republican U.S. Sen. Rob Portman and former Vice President Dick Cheney on gay marriage.

Arguably the leading advocate in the Michigan legislature for prison reform is Joseph Haveman. No one in the state House is more conservative than this Republican from Holland, Mich. But Mr. Haveman, a devout Christian, has done volunteer work in prisons. He has come to know at least a few of the men and women inside them. He knows that Michigan and the rest of the country locks up, and gives up on, too many Americans.

Maybe that won’t change much until everyone has a family member or friend inside the walls. At the rate we’re going, that won’t be long.

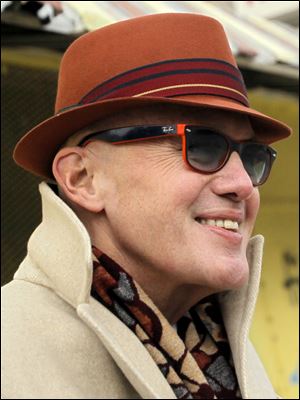

Jeff Gerritt is deputy editorial page editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com, 419-724-6467, or follow him on Twitter @jeffgerritt.