DEADLY ALLIANCE: WEAPONS OVER WORKERS

Death frees beryllium victim

Stint as secretary exposed Marilyn Miller to what would eventually kill her

2/7/2013

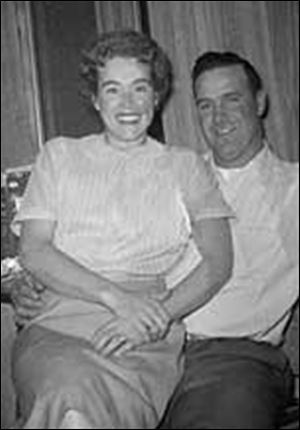

Marilyn and Jack Miller in a snapshot before she was stricken with beryllium disease.

Marilyn and Jack Miller in a snapshot before she was stricken with beryllium disease.

BRADNER, Ohio -- "Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust."

The minister bows her head, recites the Lord's Prayer, and offers the mourners huddled under the dark green canopy a final thought: "Let us go from this place in peace."

So ends the funeral of Marilyn Miller.

Family members hug each other and slowly begin heading back to their cars. Marilyn's eldest son, Mick, stops a few feet from the grave site and lights a cigarette.

What bothers him the most, he says, is that his mother never deserved this.

"It just wasn't her fault. She did nothing but work her butt off."

Only in the last couple of weeks, he says, did she complain.

"Only then did she say, 'This isn't fair.' "

Marilyn Miller died on April 13, 1998, after an exhausting, 30-year battle with beryllium disease.

She was 68 and had spent her last 10 years tethered to an oxygen tank, unable to breathe on her own.

The wife of a dairy farmer, she used to climb up in the silo and help toss out the silage.

In her last few months, she didn't have the strength to wash herself.

She contracted beryllium disease at a local Brush Wellman plant in the 1950s, when it was producing tons of beryllium metal for nuclear bombs for the Cold War. She worked there only four years, all as a secretary.

DEADLY ALLIANCE: How government and industry chose weapons over workers

She had no idea, she said in an interview shortly before her death, that beryllium dust in the plant air could lodge in her lungs and cause a fatal disease.

As difficult as her illness has been on her family, the Millers' struggle with the disease is far from over.

Marilyn's youngest son, Dave, has it, too.

She begged him not to work at the Brush Wellman plant, but the money was too good, and he didn't listen.

Mick nods toward his youngest brother, who is dabbing his eyes and crossing the cemetery.

"That's one of the things that bothered her in the last few weeks -- that he will have to go through this, too."

The Millers' story illustrates how much damage beryllium disease can do -- not only to an individual but to an entire family and community.

Day by day, the disease ate away at Marilyn's lungs. First she couldn't square dance, then she couldn't work, then she couldn't walk across a room.

And day by day, family and friends in this tiny farming town 25 miles south of Toledo watched helplessly. For there is no cure for beryllium disease.

Nationwide, hundreds have suffered like Marilyn. Locally, more than 50 people either have the disease or have already died of it.

The irony is that beryllium -- through its use in nuclear weapons -- was supposed to help protect families like the Millers.

The Millers work hard, attend church, and show cows at the state fair. One year, they were named "Ohio Farm Family of the Year" by an agricultural firm. All five children still live near the farm, and had Marilyn survived, she and her husband would have celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary this year.

Their pastor, Lisa Thogmartin-Cleaver, says the family has shown tremendous courage "to live with this disease as long as they did and live as well as they did."

Marilyn, she says, was particularly strong.

"I can't imagine having a disease that you know at some point is going to end your life. But she never seemed to let that affect her too much. She had a wonderful sense of humor and a wonderful spirit."

•

This story begins on an icy morning in January, 1998. The Miller farm, 160 acres with a big white barn, is quiet and still. Several cows stand near the road like statues.

When a visitor pulls in the driveway, Marilyn can be seen peering out the kitchen window. She opens the door with a smile and extends her hand.

She is a petite woman with a pointed nose, short hair, and gold-rimmed glasses. She is wearing jeans, a pullover shirt, and her oxygen hose -- a tiny tube that slips around her ears and into her nose.

She sits at the kitchen table and says she wants to tell her story. She wants people to know how she got this disease and what it has done to her.

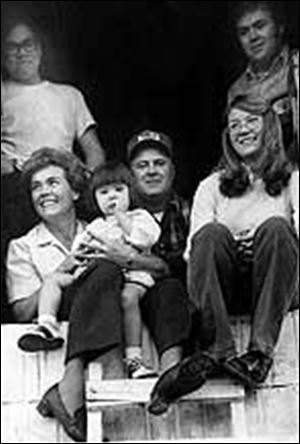

Mr. and Mrs. Miller surrounded by their children: Dave (clockwise from top left), Mick, Sandy, and Lori in her mother's lap.

Her husband, Jack, a 72-year-old who still gets up at 5 a.m. to milk the cows, sits across from her and says she looks good today.

"I can tell if she's having a good day if the bed is made," he says. "If I have to make the bed, I know she's having a bad day."

"The last few days I've been pretty good," she says, smiling.

"Bed's made," he says.

She laughs, then tells a story about a doctor who thought green beans played a role in how she felt.

"Either I should eat them, or I shouldn't. I can't remember," she says, waving it off with a hand.

She laughs, she jokes.

It's hard to believe she's really that sick.

•

Marilyn grew up not far from here, on a farm in Wayne, Ohio She worked as hard as the men, pitching hay, hauling manure, shucking corn. She grew so strong that when she was a freshman at Montgomery Local High School she could throw the shot put farther than the boys.

And she was a pretty girl, a cheerleader with thick hair, penetrating eyes, and a mischievous smile.

She met Jack when she was 18 and her then-boyfriend asked Jack to pitch for his baseball team. He did, stealing Marilyn away in the process. They were married the next year, in 1949, in a small ceremony in Jerry City, Ohio.

•

Six months later, she took a job at a factory in nearby Luckey.

It was a beryllium plant, owned by the U.S. government but operated by the Cleveland firm Brush Beryllium, predecessor to Brush Wellman.

The factory had a critical role at a critical time: The Cold War was in full swing, and beryllium was needed for America's nuclear weapons.

Marilyn didn't give it much thought. She was just 19, and to her, this was just a job -- her first real job.

She earned about $50 a week working as a secretary -- typing, filing, answering the phones. Never, she says, did she think she was in danger. She says no one told her beryllium dust could harm her, that workers in other plants had died, or that her plant was exceeding safety limits.

"If I had known that I wouldn't have worked there."

Still, she was only near the big, dust-generating machines once a day -- to collect slips of paper with numbers on them. She can't remember what the numbers stood for, but she had to carefully log them into a book, sometimes rubbing her tired eyes when she was through.

One year, her face broke out in a rash so severe that her eyes swelled up and she could barely see. Again, she had no idea that it was a sign that she might be susceptible to a fatal disease.

Four years later, in 1953, she was laid off and never went back. With two children to raise, she had other things to do.

•

In 1965, when Marilyn was 35, she noticed she kept running out of breath.

"People could go out square dancing and dance up a storm, and I couldn't finish one set," she recalls.

She thought she was just getting old. But when the problem worsened, she went to her family doctor.

He couldn't figure it out, so he sent her to a specialist, who suspected beryllium disease. He sent her to Brush's physician, who sent her to the Cleveland Clinic. There, in 1969, beryllium disease was confirmed.

Her first reaction: relief.

She was deathly afraid she had emphysema -- a disease she knew could tie her to an oxygen tank.

Whatever this beryllium disease was, she thought, it couldn't be as bad as that.

•

For the next 10 years, strong medication, such as steroids, kept Marilyn's disease in check.

She kept her job as a rural mail carrier as it didn't require much exertion. Most of the time was spent driving from mailbox to mailbox.

But in 1982 she got pneumonia and had to take three months off. She tried coming back to work, but she was just too weak, and she never worked again.

"As long as I didn't do anything I was fine, like now, sitting here," she says, spreading her arms across the kitchen table. "But with the least exertion, I was huffing and puffing."

A few years later, she had to start using oxygen.

•

Two oxygen tanks the size of old milk cans were brought out to the Miller farm. One was placed in the living room, one in the bedroom. The tanks pumped pure oxygen through a long, skinny hose, worn on the face.

For people like Marilyn, an oxygen hose is a lifeline. Without it, they can't go outside, walk across a room, or summon the strength to wash themselves. But it is also a leash, limiting where they go and for how long.

Marilyn wore the hose 24 hours a day, though at first she was embarrassed to carry her portable tank in public.

"Now I don't care," she says. "Let them stare if they want."

For several years, the oxygen allowed her to live a fairly normal life. But as her disease progressed she found she was breathless even with the oxygen.

And simple infections became major problems. Just in the last year, she says, she had to be hospitalized three times for pneumonia.

"Every time it takes longer to recover," she says.

Jack takes off his hat and runs his hand through his speckled hair.

"I think Brush Wellman owes her something," he says. "She can't clean. She can't cook. We can't go no place. We should be retired."

He wants to sue the company, but Marilyn is against it.

"That would make me nervous more than anything. What if workers' compensation stopped paying for this?" she says, holding up her oxygen cord.

Besides, she says, "You're never going to win. They have too many lawyers. They have too much money behind them."

The conversation ends like it began: politely, pleasantly.

Call, they say, if you need to know more.

•

Two weeks later, Marilyn is in Wood County Hospital, Room 203. She is sitting up in bed, her face drawn, her hair sticking straight up.

"I was coughing all weekend, coughing and coughing, and I woke up Tuesday with a fever; so I thought I'd better get in here."

Unlike two weeks ago, she now labors for every breath. When she tries to joke about her hair, her chuckles turn to coughs and she stops. "It just seems like there's something in there I can't get out."

Dr. David Atwell comes in and asks how she's doing.

"Not too good," she says.

He listens to her back and says she might have a fungus in her lungs. They hope to find out what kind so they can treat it. Otherwise, they'll keep her on general antibiotics.

"She has a fair amount of scarring of lung tissue, so she has trouble fighting off the infections," he says, putting his stethoscope away. "But she has a good attitude. So does her husband. That's important. It's important to have a good support system."

•

The following night Marilyn is still coughing but in better spirits. Jack and their son Dave are there, talking about how a Brush Wellman official, Dennis Habrat, had briefly visited Marilyn.

She is impressed that he would drive two hours from Brush headquarters in Cleveland to see her.

Her husband scoffs at this, saying he's a big city executive trying to charm the country folk so they don't sue.

"You know what he came in here wearing?" he says. "A flannel shirt."

"It was not a flannel shirt," she says.

"Oh, yes it was. He's really, really smooth."

"Well, I thought he was nice."

"You're a bit naive."

"I guess I am," she smiles. "I married you."

Respiratory therapist Erma Hillard announces it's time for a breathing treatment. She has Marilyn breathe through a T-shaped inhaler, then she rubs a vibrator on her back to loosen the mucus stuck in her lungs.

"She has a lot of secretions in her airways," the therapist says. "That's what you hear rattling around in there."

When the treatment is over, the therapist listens to Marilyn's lungs.

"Does that lobe sound better than the other one?" Marilyn asks hopefully.

"They all sound pretty full right now," she replies.

Watching it all is Dave. The 39-year-old in jeans and work boots leans against the wall and doesn't say a word.

He knows that someday that may be him in a hospital bed.

•

Dave went to work at Brush Wellman in 1980, a dozen years after his mother was diagnosed.

He did so over her objections, he says, because the pay was good -- $8.26 an hour -- and Brush assured him that its new plant in nearby Elmore, O., was safer than the one his mother had worked at in Luckey.

He worked in a variety of jobs -- some having high beryllium exposure levels. In fact, Brush records show Dave worked in areas that repeatedly exceeded the federal safety limit for beryllium dust.

Dave says he was more than careful: "I was paranoid. I was a butt of a lot of jokes for wearing respirators more than I was supposed to."

But three years after he started work he came down with flu-like symptoms and was diagnosed with beryllium disease.

"Mom was more upset than I was," he recalls. "She knew what was coming."

Like his mother, Dave was put on powerful medication. He still looks healthy, even athletic, but his lung capacity is down to 75 per cent.

He remains employed at Brush but under a company program that removes beryllium victims from the plant and puts them into community service jobs. Dave cuts grass and picks up trash near Toledo's Old West End neighborhood, where he has bought and fixed up several old homes.

Because beryllium disease affects people differently, there's no way to know how sick Dave will become. A third die of the disease, a third become disabled, and a third remain relatively healthy, doctors say.

Dave's physician, Dr. Vijay Mahajan, is optimistic, saying Dave has responded well to steroids.

Dave is not so hopeful: "I'm on the downhill slope."

•

After a few more days in the hospital, Marilyn comes home, but she doesn't feel much better. She spends most of her time lying on the couch.

One day, after a big spring storm, her eldest son, Mick, comes over to pick up the sticks in the yard -- something his mother is particular about.

Usually when he comes over she looks out the kitchen window and waves.

This time she doesn't.

And when he comes in and tells her there are still some sticks to be collected, he expects her to say, "Well, get at it!"

But she says nothing.

•

The first week in April she is back in the hospital, this time Medical College of Ohio Hospital in Toledo.

"I didn't think she would make it through the night," her husband says over the phone. "They called us all up there last night. I'm not exactly sure why. A couple, three priests were up there."

Doctors can't do much, he says.

"She has no lung capacity. There's no way for her to get air in. She can't eat. She's too weak to talk, maybe a whisper, if she's awake."

•

Marilyn Miller was 19 years old when she took a job as a secretary at the local Brush beryllium plant. She worked there for only four years but that was long enough for her to contract the disease that would take her life. She died the day after this photograph was taken.

The next 48 hours seem like weeks. Relatives come and go. Nurses give her more breathing treatments. Dave tries to keep her cool by wetting her face and arms with a washcloth.

She now has a feeding tube in her nose and a mask blowing oxygen in front of her mouth. Her heart rate bounces between 105 and 125.

When nurses shove a tube down Marilyn's nose to suck out phlegm, family members avert their heads or go into the hall. Marilyn coughs, gags, and moans, and greenish mucus is extracted.

On Easter Sunday, she can barely whisper, but she manages, "Jack, Jack." Lori, at age 28 her youngest child, phones her father and says he'd better come back in. He does, but she is highly medicated and sleeping when he arrives.

A few hours later, at 4:30 a.m. Monday, her vital signs are out of control. A doctor tells Lori she'd better call her family again.

She does, but by the time they arrive, Marilyn is dead.

•

When the family returns to the Miller farm, one of the grandsons is cutting the grass.

Mick asked him to do it, because that's what Marilyn would have wanted. Have the yard look nice for everyone who will be stopping by.

Doug, her 44-year-old son, walks into the house via the garage, slapping the side of a spare oxygen tank. "Well, we're not going to need this any more," he says.

They all flop down in chairs. Marilyn had pulled through so many times. They can't believe she didn't again.

When Jack comes inside, he pulls out his address book and starts dialing Brush Wellman.

He asks for Dennis Habrat and is put through to his voice mail. He leaves the following message:

"This is Jack Miller. Marilyn isn't with us anymore. Better tell your lawyer fast."

Charlie Barndt, the local funeral director, arrives at the Miller home at 1 p.m.

He is a large, friendly man in a gray suit and a white, pencil-thin mustache. Jack has known him for years, ever since their old baseball days.

Charlie gathers the family in the living room, and, clipboard on his knee, goes over the funeral arrangements.

"Do you want Bradner Cemetery?"

"Do you want to order the flowers yourself?"

"Who does her hair?"

Dave looks the worst, sprawled in a corner chair, head back, staring at the ceiling.

The group then squeezes into two cars and drives into Bradner to pick out a casket.

They pull up to a white, windowless building on Main Street, and Charlie unlocks the front door. Inside is a wood-paneled room lined with 24 caskets.

Charlie takes the family counter-clockwise around the room, describing each casket in hushed tones. When he's shown them all, Jack nods politely, and Dave leans his hand on a copper casket and stares through it.

The family eventually decides on a stainless steel one with a pink interior.

When they return home, Sandy, the older daughter, looks at all of the cars parked out front.

"Looks like we're having a party," she says softly.

•

The viewing is in the Barndt Funeral Home, a converted, two-story house in Wayne. Dozens of people show up, and more than 80 bouquets are brought in.

Two are from Brush Wellman.

Old friends and neighbors pat Jack on the back and say they are sorry. "She just couldn't breathe anymore," he tells one friend.

Even more people attend the evening showing.

In one corner, three men sit quietly. At their sides are their portable oxygen tanks.

All three men -- Butch Lemke, Bob Szilagyi, and Gary Renwand -- worked at Brush Wellman in Elmore and all three have beryllium disease.

Butch says this is his third funeral of someone who has died of the disease.

"This is my fourth," says Bob.

"This is my fourth, too," Gary says.

Then they list them and realize they forgot one. So this is their fifth.

•

The funeral is the following morning at St. James Lutheran Church in Bradner.

It is so packed that the funeral director has to set up extra chairs in the back.

The Millers sit up front, red-faced and in tears. In the back, in a dark suit, is Mr. Habrat from Brush Wellman.

Pastor Thogmartin-Cleaver addresses the group:

"When we lose someone we love, we want to know why. We want to blame someone. . . . There are no human words or gestures that can take away the grief you are feeling now. There are, however, promises of eternal comfort which were fulfilled for Marilyn on Monday morning when she passed over into the next life and found herself with God."

At Bradner Cemetery, after all of the mourners have departed, Lester Sterling, a third-generation gravedigger, buries Marilyn.

"Yeah, I knew the family," he says. "I knew Mick, and my dad went to school with Jack. That's the thing about this job: Half the people you bury you know; the other half are your cousins."

He fills in the grave with a shovel. When he is done, he carefully replaces the squares of grass, then piles several bouquets of flowers on top.

The sun is out now, and the gravedigger wipes his brow.

"Well, at least she made it through Easter."

Brush Wellman's Mr. Habrat says the company did everything it could to help Marilyn. It helped arrange the best medical care and gave the family more than $25,000 in the last five years.

He would come out to the farm and hand-deliver the checks. Once, Jack was in the fields so he left the check inside the door.

The money wasn't to fend off a lawsuit, says Mr. Habrat, Brush's director of occupational health affairs. "We wanted to ensure that whatever Marilyn needed it would be available to her."

Brush does this for other victims, he says. He often visits their homes, asks how the company can help, passes along some money.

He knows the families are skeptical and angry.

"These are difficult situations," he says. "I wish they were different. I wish I could do something to cure the person or make the disease go away."

•

Two weeks after the funeral, Jack is sitting on a bench outside the barn, petting his brown shepherd, Tammy. Mick is nearby, sitting on a plastic bucket flipped upside down.

It is a gray, drizzly morning, and the two have just finished milking the cows. A few minutes later, Dave pulls up in his pickup truck.

The three talk about the good times, Marilyn's final days, and whether they could have done more to help.

Mick tells a story about how a few years after Marilyn was diagnosed she was driving down the road and saw an old woman planting flowers.

"It was a big beautiful display, and this woman was 80 years old, and Ma said to me, 'I'm just never going to be an old lady planting flowers.' "

They talk about whether they should sue Brush Wellman, how Jack will handle living alone, and what can be done to help Dave.

Jack says he doesn't know much about beryllium disease, or who's responsible, but it needs to stop.

"How many Marilyns you want out there?"

With that, Dave climbs back into his truck, Mick goes back into the barn, and Jack heads into the house. For now, they say, there are chores to do.