As empire unraveled, a sad exit

3/11/2001

Haphazardly filed business papers await examination in a downtown law office.

The mystery of Shale Dolin's demise may never be solved. But some clues as to why the popular owner of three pharmacies and several other businesses in the Toledo area killed himself last summer lie in bags and boxes of financial records in a law office in One SeaGate.

Others are in hundreds of pages of court documents that form a foot-high stack of paper headed for trials, beginning next month, in six cases in four courts.

What is clear, however, is that Mr. Dolin's death at the age of 61 apparently stemmed from his despair over financial problems that he kept largely to himself. Evident, too, is that he had persistent business management problems, which also were not widely known.

He had dozens of court judgments and liens going back 15 years, bills that couldn't all be paid, and millions of dollars' worth of checks, floating from bank to bank, that began bouncing in the days before his death.

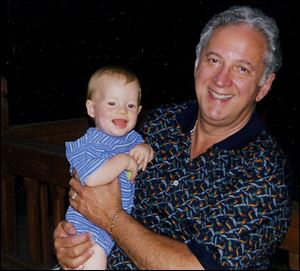

Shale Dolin presented a smiling outlook in a 1999 family photo.

Friends and associates offer some reasons why three Shale's pharmacies in the Toledo area closed suddenly after Mr. Dolin's death. Perhaps, even with 38 years of experience in the drugstore business, he couldn't compete with the big chains. Perhaps he was too kind to some of his customers, allowing many senior citizens to run up large drug bills only partially covered by prescription plans. Some say he bit off more than he could chew: He opened too many new businesses in recent years. Others say he was not a good businessman, as evidenced by messy record-keeping.

Six months after Mr. Dolin's death, nearly everyone who knew him agrees it was a strange, sad, troubling end to what was once one of the largest local pharmacy operations.

“The thing that bothers me is that with all the friends he had, why didn't he talk to anybody?” asked Robert Morason, a friend of Mr. Dolin since both were students at the University of Toledo. “He [apparently] had overwhelming problems, but when he talked to me, he was the same old Shale.”

“Men do not talk,” said his widow, Sue Anne Dolin, trying to explain why her husband killed himself. “They can't tell anyone their problems. They hold them inside.”

Haphazardly filed business papers await examination in a downtown law office.

Mrs. Dolin, now a defendant in several of the lawsuits - as executrix of the estate and as co-signer on contracts for the pharmacies - added that she has joined a support group for survivors of suicide.

She found her husband's body in their garage on Corey Cove in Sylvania Sunday morning, Sept. 17, last year.

Even though Mr. Dolin was Jewish, he often went to his wife's church, Epworth United Methodist, to hear her sing in the choir. But that morning, he was staying home with a chest cold. Shortly after his wife left for church, Mr. Dolin made the bed, raised the windows in their condomonium, left three messages on the telephone recorder, and went to the garage. He sealed off the garage door and lay under his car's exhaust pipe. He raised the windows, his family and friends imagine, to protect the couple's two cats.

Shortly after his death, it became clear that something was radically wrong with the business, and his finances.

A pharmacy employee recalled that Mr. Dolin bought $200 worth of lottery tickets - far more than the $10 he usually spent on the lottery - on Saturday, the day before his death, which was ruled a suicide. His wife remembered that he had received a call on Sept. 15, two days before his death. She thinks it may have been from a bank, and she said her husband told the caller he was aware of the “problem” and would take care of it.

Whatever the problem was - possibly it was his notification that checks would soon bounce - it didn't keep him from socializing with friends that weekend. He went to a Toledo Symphony pops concert at the Stranahan Theater.

In the following days and weeks, the news about Mr. Dolin's businesses got worse. On Sept. 28, all three of his remaining stores closed abruptly - Shale's Downtown Pharmacy & Ice Cream Parlor, in the former Lasalle's department store (restored as LaSalle Apartments), Shale's Campus Pharmacy & Coffee Shop on Bancroft Street next to the University of Toledo, and Shale's Perrysburg Pharmacy, on Louisiana Street in downtown Perrysburg.

Employees had only a few hours' notice to shut the doors, and many of the 30-some workers never got paid for their last week or two of work. Some paychecks they did get bounced. All together, checks written on Shale's accounts at Mid Am Bank (now known as Sky Bank) and KeyBank totaled nearly $3 million, almost all of which bounced.

Within weeks the lawsuits started flying. Nearly every level of court in Toledo has some filing. Among them are Lucas County Common Pleas Court, which will handle three suits totaling $2 million in claimed damages against Mr. Dolin's estate and his wife, as executrix and co-signer of various bank loans and contracts; Lucas County Probate Court; and U.S. District Court, where two of the largest banks in the region and two big law firms representing them are battling over $1.1 million in Shale's Pharmacy checks.

On Nov. 9, the pharmacy chain, under the umbrella of Shale's Talmadge Pharmacy, Inc., landed in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Toledo - with assets of less than $1.4 million and liabilities of $3.2 million.

The mound of court documents reveals a collection of businesses, some growing while others were struggling, and 40-plus court judgments and liens against Mr. Dolin and his businesses, dating back 15 years in some cases.

Some court actions are unlikely to be resolved until the Common Pleas and federal cases are settled. For example, as of last week, probate court didn't even have a complete inventory of Mr. Dolin's assets.

Over the years, Mr. Dolin had an amazing entrepreneurial zeal, starting a dozen or more businesses ranging from pharmacies to restaurants, self-storage buildings, and a shopping center.

At one time, he owned seven drugstores, but he sold stores on Talmadge Road, Secor Road, West Central Avenue, and in Perrysburg on Dixie Highway. Of the remaining three, he seemed especially proud of the one downtown, which opened in July, 1998, amid significant publicity about it as a sign of downtown revitalization.

“This is my baby,” Mr. Dolin said at the opening of his 5,600-square-foot store that included a 52-seat 1950s-style diner. He spent $100,000 refurbishing the building and was optimistic that with more Toledoans living downtown the business would thrive.

Mr. Dolin had a fascination with restaurants, and over the years he opened several, including two on Monroe Street - Cagni's and Benny's Deli - in the early 1980s. Benny's Deli was named for his father, Ben, and one of the sandwich specialties, Millie's 3 Sons, was named for his mother.

His friends and employees spoke of him as kind, charming, and friendly with customers and workers alike. He apparently never told even his closest friends that his financial world was collapsing and that he was facing severe consequences for what banks now say was a huge check-kiting scheme that may have been going on for months before his death.

One aftermath of Mr. Dolin's demise is a federal lawsuit pitting two of the city's biggest banks and their lawyers against each other to determine which will get stuck with more than $1 million worth of bounced checks that Mr. Dolin apparently wrote on Sept. 12, five days before he died.

One exhibit shows 11 checks, numbered sequentially, for amounts between $90,407 and $93,701. Mid Am Bank (now Sky Bank), represented by Eastman & Smith, sued KeyBank, represented by Connelly, Jackson & Collier, for $1 million in damages, contending that Key failed to return the bad checks in a timely manner as required by the Federal Reserve, so the bank ended up honoring them and now is out the money. The case is not likely to be heard before summer.

In Common Pleas Court, Mid Am, KeyBank, and Exchange Bank sued Mr. Dolin's estate and widow for a total of $2 million involving the checks, overdraft agreements, and commercial loans - $1.2 million by Mid Am, $915,000 by Key. Exchange Bank is seeking $74,000 it says is owed on a commercial overdraft line of credit. In the pending probate case, Mrs. Dolin has a claim against the estate for $100,000 she says her husband borrowed from her and hadn't repaid.

Among the Dolin family assets that will be contested in the suits are life insurance policies totaling $440,000, brokerage investments of $390,000, and two businesses unrelated to the pharmacies - Village Square shopping center in Perrysburg and Storage Corral, a collection of buildings housing 13 self-storage sheds and several office/warehouse units off South Avenue in Springfield Township.

Gary Hahn, the local contractor who built the shopping center and the first two buildings of Storage Corral - out of 13 planned on the 12-acre site - said he is considering suing for up to $35,000 he says he wasn't paid on the initial $538,000 project. “It ended up costing more money [than planned],” he said, because of Mr. Dolin's changes.

“In the end, it was too difficult to work with him,” Mr. Hahn said. “He was a nice guy, but he always tried to get too many fingers in the pie. I would never have done anything else with him.”

A former adviser to Mr. Dolin, who spoke only if not identified, described Mr. Dolin as “a horrible businessman, always robbing Peter to pay Paul. He would do things beyond belief. He was always living on the financial edge, one step away from bankruptcy.”

Mr. Dolin's Monroe Street restaurants were doomed from the start because of extravagant lease charges, the former adviser said. “He was told by me and others, `This is crazy; you can't do it.'”

Even Mr. Dolin's accountants apparently were left in the dark at times. One financial statement for Shale's Talmadge Pharmacy showed after-tax profit of just $1,407 in fiscal 1999, after earnings of $222,000 in fiscal 1998, and salaries for Mr. Dolin of zero in 1999 and $50,000 in 1998.

However, the accounting firm of Lublin Sussman Rosenberg & Damrauer added a disclaimer: “Management has elected to omit substantially all of the disclosures required by generally accepted accounting principles. If the omitted disclosures were involved in the financial statements, they might influence the user's conclusions about the company's financial position.”

The former Shale's Pharmacies are history. Bankruptcy trustee John Graham said the inventory and sale of hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of drugs was a particularly difficult process, requiring pharmacists to be on hand, notification of drug-enforcement agencies, enhanced police surveillance, and the use of a local firm, Prescription Supply, Inc.

Among the Shale's employees owed money is Anita Tuckerman, whose last two payroll checks bounced. A pharmacist in the downtown store who now works for St. Charles hospital pharmacy, she filed a bankruptcy-court claim for $4,536.

Still, she said she holds no grudge. “He would do anything for his customers,” said Ms. Tuckerman. “He would take stuff to them after work, make deliveries to people who couldn't get out.” She said the downtown location “was doing fairly well, as far as I know.”

A number of Mr. Dolin's friends and associates said he told them it was getting increasingly difficult for small, independent druggists to compete with big national chains. “He said there's just no money in [local] pharmacies anymore, the dollars just aren't what they used to be” said Dr. Morason, a dentist and one of his close friends.

“He had really overwhelming problems,” said Dr. Morason. “He just got to the point where he was overextended. But he never mentioned anything about any sort of financial problem.”

Another friend, Sarna Dorf, a Realtor, said, “It seems like things sort of snowballed.”

She said many judgment liens were filed against him that he didn't tell people about. Just days before his death, she said, Mr. Dolin was talking about getting some new tenants in his properties and about a vacation he and his wife had taken.

Like others, Ms. Dorf wondered, “If he had come to us, maybe we could have helped him.”

Mrs. Dolin said the three messages her late husband left on the recorder were very personal, along the lines of, “I love you. Be strong.” In one of the messages, he said, “I've worked hard all my life,” and alluded to his business problems.

“Shale was so positive, so upbeat, he's the last person you would expect to take his life,” Mrs. Dolin remarked. “No one was more stunned than I.”

When the Dolins were married in 1992, his sons (one a lawyer, the other a psychologist) were grown, but Mrs. Dolin's son and daughter were teenagers.

“He was the most understanding stepfather any child could have,” she said. “He encouraged my daughter to be a doctor, and by next year we'll have a doctor in the family.”

Mrs. Dolin said she believes “he took his life so mine could continue.” But, she added, “he didn't keep his promise that we would grow old together.”