At 120, Toledo's Libbey looks to its future

5/18/2008

Libbey factory" rel="storyimage1" title="At-120-Toledo-s-Libbey-looks-to-its-future.jpg"/>

Libbey factory" rel="storyimage1" title="At-120-Toledo-s-Libbey-looks-to-its-future.jpg"/>

Constantly burning natural-gas-fed flames keep the glassware at the proper temperature as it moves through the historic factory on Ash Street. <br> <img src=http://www.toledoblade.com/graphics/icons/photo.gif> <b><font color=red>VIEW</b></font color=red>: <a href=" /apps/pbcs.dll/gallery?Avis=TO&Dato=20080518&Kategori=BUSINESS03&Lopenr=754667712&Ref=PH" target="_blank "><b>Libbey factory</b></a>

BEFORE SOLAR panels, before axles or spark plugs, before Jeeps or scales, before insulation or glass bottles, a company came to Toledo on a train, bestowed a nickname on its new city, and never left.

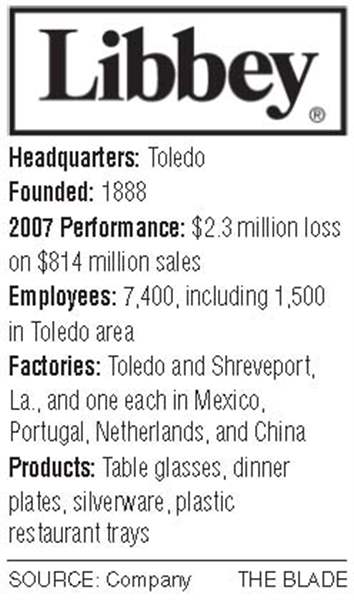

That company, Libbey Inc., celebrates this year the 120th year of its arrival in Toledo and of the Ash Street plant that has employed tens of thousands of local residents and artisans over the decades.

But more important, the firm finds itself at a crossroads financially.

The company whose glassware is a part of many restaurants and home dinner tables has spent the last three years undergoing a stunning transformation into a global manufacturing powerhouse - although one heavily in debt.

New factories in China and Mexico have allowed Libbey to increase its revenues from under $434 million in 2002 to an expected $870 million this year and $1 billion by 2010.

Its Chinese factory, which began operations in early 2007, now exports to 30 countries.

Its Mexican factory makes 63 percent of the glassware for the Mexican market.

At the end of 2007, Libbey had more than $500 million in outstanding debt - some of it at annual interest rates as high as 16 percent - that it is actively seeking to refinance when market conditions allow.

"We are mindful of the fact that our transformation is not yet complete, but significant progress has been made," said Chief Executive John Meier. "We are in the 10th period of our 10-period game, and we are driven to achieve our goals."

Although he assured shareholders this month that Libbey is committed to the U.S. retail and food-service markets, he noted its large and growing international footprint. In 2002, just 11 percent of Libbey's sales were outside the United States, but now that figure is more than 45 percent.

And during that period, the proportion of employees in plants outside the country went from 13 percent of a work force of 3,800 to 61 percent of a total of 7,400.

Libbey is to open the doors of its downtown showroom to invited guests on May 28 for a celebration of its 120 years in operation.

The company's story began when, enticed by the promise of cheap and plentiful natural gas and the proximity of nearby raw materials, Edward Drummond Libbey signed a contract on Feb. 6 , 1888, to move his New England Glass Works from Boston to Toledo.

The plant was built on what was then farmland northeast of downtown, and opened on Aug. 17, 1888, after more than 50 train carloads of equipment and workers were delivered from the East Coast to Toledo. They were greeted with a parade.

Mr. Libbey later hired a superintendent for his factory, a mechanical genius by the name of Michael J. Owens, who along with his benefactor gave Toledo its nickname of "The Glass City."

The two not only transformed the way glassware was manufactured - from handmade to automated - but started other local glass-related ventures that grew into some of Toledo's largest companies, Libbey-Owens- Ford Inc., Owens-Illinois Inc., and Owens-Corning Inc.

The Libbey factory on Ash Street.

Along with a machine to automate the making of bottles and later glassware, Mr. Owens developed a machine in 1904 to mass-produce light bulbs, which had been hand-blown. That technology was transferred to Westinghouse Inc., or Toledo might have been the light-bulb capital of the world.

During World War II, the Libbey plant made glass bulbs for radar tubes, serum ampules, and lenses for airplane wing-tip lights.

O-I bought Libbey Glass in 1935 and kept it as a subsidiary and later a division, for almost 60 years. It spun it off in 1993, and Libbey started selling shares of stock to the public.

Its Toledo facilities remained the heart of the company, even as the home factory became its most expensive plant to operate, Mr. Meier said. Its researchers and designers create products from a small group of offices not far from its loading docks.

And when Libbey opened its sparkling new factory in China in 2006, the proprietary machines that make it so efficient were built in Toledo and exported.

The largest and oldest continually operating glass factory in the United States, Libbey's huge plant on Ash Street makes as many as 120 million pieces of glassware a year, from tumblers to vases to stemware to shot glasses.

The plant ships 3,000 different items, and over 10,000 different packaging derivatives of those items, plant manager Bill Herb said. The packaging includes Libbey products with the trademark cursive "L" and private-label boxes for retailers as diverse as Crate & Barrel and Wal-Mart.

Mr. Meier, who also is company chairman, said this month that Target Corp. had dropped its private-label glassware in favor of Libbey brands.

The glass-making process is an elaborate choreography of fire and automation, transforming seemingly inert materials into an endless line of common household products.

"It's an old plant, but the equipment is state of the art," said Ken Boerger, Libbey's vice president and treasurer.

The glass factory owes at least part of its long history to its location. Mr. Libbey chose Toledo because it had a wealth of natural resources, including abundant and cheap natural gas, on site or nearby. The high-quality sand that the factory still uses comes from a quarry in Rockwood, Mich., about 30 miles north of the plant; the limestone comes from 20 miles south in Woodville. Only the soda ash comes from far away: Wyoming.

Huge furnaces blast hellish jets of flame across the 2,700-degree molten glass as sand and other materials are fed in from above with augers that keep the glowing mixture just right.

Heat from the furnaces rises up the multistory factory and escapes into the atmosphere through giant louvers on the roof.

Small chunks of the molten glass are cut and fed into spinning machines that can press it, stretch it, or blow it into shape, depending on the form attached.

For pieces with stems, such as wine glasses, a second piece of molten glass is pressed onto the first and is spun rapidly to form the base. An extra piece used for handling, called the moil, is separated from the glass and recycled.

The glassware, still handled only by machines, is placed on a conveyor and slides into a giant box, called an annealing oven, which raises its temperature and then lets the glass slowly cool, hardening it.

The glasses pass through a visual inspection, are boxed up by hand, and speed off on a conveyor system to the huge warehouse a few hundred feet away.

"Glass is all about time and temperature," Mr. Herb explained.

The level of automation within such an old facility is striking: From the time trucks dump raw materials outside the plant to the point where the glassware is inspected for flaws, Libbey's products aren't touched by human hands.

Even the pallets are automatically assembled and wrapped under computer control, and not until a forklift driver scans them for storage or delivery do they intersect with a human being again.

"Before automation, it took 35 people to [run this line]," Mr. Herb said, pointing to streams of stemware being inspected and boxed. "Now it takes four."

Of course, all the automation meant job losses for the four unions that represent workers at the Toledo factory.

It once employed as many as 1,800 people, but now has about 1,125. It has 375 others at its downtown headquarters, 300 Madison Ave.

Today, the company is in the enviable position of being a true leader within its industry.

It controls about 34 percent of the North American retail glassware market, enough to make it No. 1 on the continent, and is the No. 2 player worldwide in its industry (France's Arc International is No. 1). Its retail sales, like those from its popular factory outlet in the Erie Street Marketplace, rose 19 percent last year.

The company controls 56 percent of the food service market, meaning restaurants across the nation - from Tavern on the Green in New York City to Outback Steakhouse locations across North America - serve their food in and on Libbey products.

Those products include plates and cups manufactured in New York under the brand name Syracuse China. A third company, Traex, manufactures in Dane, Wis., the plastic trays that hold glasses and dinnerware as they are cleaned in restaurant dishwashers.

Libbey also sells utensils under the brand name World Tableware that are made by another company.

The firm received a number of "vendor of the year" awards in 2007 from restaurant chains and supply houses.

If you go out to eat today in the United States, "there's a 50-50 chance there will be a Libbey product on the table," said John Vozzo, chief operating officer of Singer Equipment Co., a restaurant supplier in eastern Pennsylvania that has bought from Libbey for 35 years.

"On the everyday stuff, they are still the dominant glass maker out in the marketplace."

But the company has some problems on the horizon, not the least of which is the ballooning price of the natural gas used extensively in the glass-making process.

Its $503 million debt - taken on in part to buy out its former partner in its Crisa operation in Mexico as well as to build and open its plant in China - has left the firm with more debt than is considered desirable and is in need of refinancing, company executives said.

And that's not easy to do in today's tight credit market, no matter what a company's performance has been.

The company last week registered its intent to sell bonds or stock for up to $500 million, proceeds from which will be used to pay off some debts.

Jim Barrett, an analyst with CL King & Associates, of New York, said Libbey's management knows the issues facing the company and is just waiting for the best time to fix them. He is a Libbey stockholder, and his firm has advised its clients to accumulate Libbey's stock.

The company also has been affected by the downturn in the U.S. economy, he said.

"They depend on you and me going out and eating at the fast-casual dining chains which have real glasses that can break," Mr. Barrett said. "When people stop going out to eat so much, that makes [ Libbey's] end markets weaker in certain respects."

The firm's stock has sometimes struggled. It sold for nearly $30 a share in 2004 and as low as $6 a share in 2006. It closed Friday at $11.91.

Greg Geswein, Libbey's vice president and chief financial officer, told analysts this month the company has the opportunity to refinance some of its highest-interest debt next month and again in June, 2009. But investors and lenders will have to show some faith in the company - via lower interest rates - for the refinancing to work.

"For us to punch that [refinancing] ticket, we have to get a much-better [rate] than what we have today," he said. "We could probably improve on what we have, but it probably doesn't make sense unless we could get a really good deal."

Contact Larry P. Vellequette at: lvellequette@theblade.com or 419-724-6091.