Deportation breaks apart families in Ohio, across nation

Immigration reform may come too late for 200,000 separated in 2-year period

4/15/2013

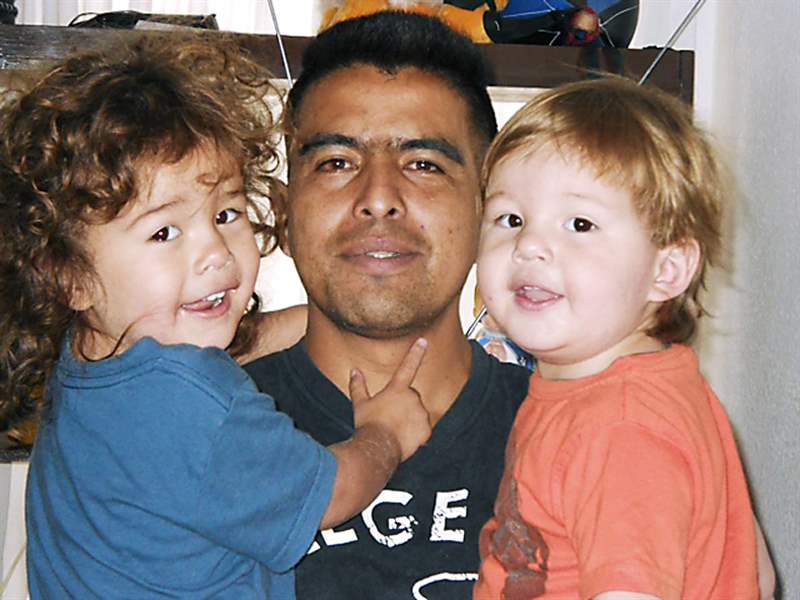

Moments like this one in which Marcos Perez enjoys time with sons Ignacio Pele Perez, left, and Marcos Antonio Perez are now rare. Mr. Perez was deported to Mexico three years ago.

NOT BLADE PHOTO

Moments like this one in which Marcos Perez enjoys time with sons Ignacio Pele Perez, left, and Marcos Antonio Perez are now rare. Mr. Perez was deported to Mexico three years ago.

It was three years ago, early morning, when Elizabeth Perez returned to her Cleveland home from the doctor’s office with good news to tell her husband, Marcos: She was pregnant with their second child.

For several moments, they celebrated with kisses, hugs, and tears of joy. Mr. Perez headed to work. A few minutes later, he was pulled over for a traffic-stop violation. Less than a month later, he was deported to Mexico City.

“Noooooo!” Mrs. Perez wailed into the phone receiver when immigration authorities called to inform her that her husband had been apprehended.

Mr. Perez would not be at his wife’s side when she gave birth to Marcos Antonio Perez. He would not be there to watch his eldest son, Ignacio Pele Perez, celebrate his second and third birthdays.

“I never feel such pain,” Mr. Perez said to The Blade in a telephone interview from his home in Mexico.

His words were interrupted by the sound of him sobbing uncontrollably.

“Oh, Jesus, it’s terrible. I want to be with my children. I want to be with my wife.”

The Perezes are not alone in their pain. More than 200,000 immigrant families have been torn apart during the past two years in the United States, according to a recent congressional report.

Even as a bipartisan group of senators wraps up work on a comprehensive reform bill that is expected to include a pathway to citizenship for millions of illegal immigrants living in the United States, it may be too late for many families who’ve already lost loved ones to deportation.

Pro-immigration advocates such as Baldemar Velasquez, president of Toledo-based Farm Labor Organizing Committee, have been calling on lawmakers to temporarily halt deportations of illegal immigrants who have not commited crimes in the United States, pending the outcome of the immigration reform efforts. The request largely has been ignored.

“Does it make sense to continue to deport nonlaw-breaking immigrants while we work on immigration reform?” Mr. Velasquez asked. “Why do you want to continue to break up families?”

Reform efforts

That question is at the heart of the anguishing immigration reform debate, with conservatives typically advocating that people who entered the country illegally continue to be subject to deportation, and others advocating for a “path to citizenship.”

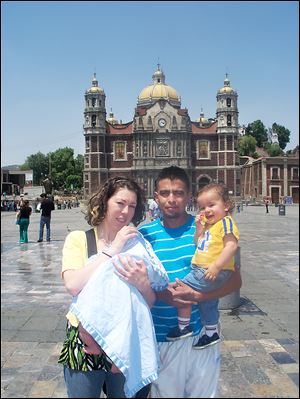

The Perez family visits the Basilica in Mexico City. The only way Elizabeth Perez and the children can now visit Marcos Perez, center, is by traveling to Mexico.

Senators working on an immigration bill reportedly have agreed that foreigners who crossed the border illegally would be deported only if they entered the United States after Dec. 31, 2011.

The legislation by a bipartisan group of senators would give the estimated 11 million immigrants living in the United States illegally a way to obtain legal status and eventually become U.S. citizens, provided certain measures are met.

Mrs. Perez loves her country. It’s the reason she served in the military for 10 years, including five in the Marine Corps, where she quickly attained the rank of staff sergeant.

“I got out because I wanted a family,” Mrs. Perez, 34, said. “I didn't want to be in the military, always separated from my family.

“Ironically, that’s what happened with my husband.”

Sharing her story is painful.

It’s been three long years. The couple is separated by thousands of miles.

Mrs. Perez attends Cleveland State University and is scheduled to graduate in May, 2014, with a bachelor’s degree in social work. Mr. Perez, who is qualified to teach secondary education in Mexico, works instead as a community soccer referee — a Friday-through-Sunday job that pays him $90 or more per week — double what he would make as a teacher.

“I’ll never forget that day,” Mr. Perez told The Blade during the Thursday telephone interview. “It was such a beautiful day. I was so happy. We were going to have another baby.”

Mr. Perez, 40, was born in Mexico City. His mother, who was single and trying to raise three other children, gave Mr. Perez away because she could not afford another child.

The family that raised him abused him physically and verbally, treating him like a slave, he said.

He never met his father. He was a grown man before he met his biological mother.

Mr. Perez always vowed to himself that he would do better by his own family. He would always be there for his children.

That’s not likely to happen soon, if ever.

The road ahead

Mr. Perez has been deported twice. As punishment, he isn’t allowed to even apply for a visa until 2020.

The couple has discussed ways to be reunited. Mrs. Perez said she is willing to move to Mexico to be with her husband. He has suggested they find another homeland, perhaps Canada. Mr. Perez has talked about trying to sneak back into the United States a third time, but he said that is very dangerous and expensive.

For now, the family communicates daily by phone. Mr. Perez spends several minutes talking to his sons, “but really, they are too young to understand,” he said. There are so many things that Mr. and Mrs. Perez talk about. There are also many things they don’t share.

“It’s very lonely here, I’m always sad,” Mr. Perez admited. But he doesn’t tell his wife, because he doesn’t want her to worry.

Their boys aren’t old enough to completely understand what’s going on, but they’re aware that something’s wrong, said Mrs. Perez, who tells her children that “daddy is at work.”

“Sometimes I catch Marcos pretending to talk to his dad on his toy phone,” Mrs. Perez said. “On Christmas Day, the boys were playing with their new toys. Ignacio was just sitting there and suddenly started screaming, ‘Where’s my daddy, where’s my daddy?’ ”

Elizabeth Perez encourages the audience to Save Our Families during a town-hall meeting on immigration at the Driscoll Alumni Center at the University of Toledo.

She doesn’t tell her husband about these incidents because it would only add to her frustration, Mrs. Perez said.

The Perezes are both excited for Mrs. Perez’s spring semester to end in May. She and the boys will head to Mexico City so the family can reunite for a couple of months.

A sense of betrayal

The separation is still a bitter pill to swallow.

“I feel like I dedicated 10 years of my life serving my country," Mrs. Perez said. “I served in Afghanistan. I was willing to die for my country. I was always very patriotic.

“But now I feel like this isn't fair — I have to wait at least 10 years before I can be with my husband again. It does frustrate me.

“I feel betrayed,” she said. “I don’t like my country very much right now."

Family trauma

Such scenarios of heartache have played out in the Toledo area as well.

Christopher Ramirez was 14 when he watched helplessly as federal immigration agents entered his family’s Toledo home, placed handcuffs on his father, and dragged him away to be deported to Mexico.

Several frightening thoughts crossed the teenager’s mind.

“I’m never going to see my father again,” the now 15-year-old Christopher recalls thinking, the memory causing him to choke back tears. “And then I realized, ‘I’m the man of the house now. I have to protect my two little sisters and our mom.’

“But it’s scary. I don’t know what to do. I’ve never felt this scared before,” he remembered.

A mother’s fear

In Painesville, Ohio, Cecilia Mendez has laid awake every night of the past week, worrying if the day might come when she will never see her children again.

The 41-year-old single mother of five children is an illegal immigrant. She was picked up by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents on Monday. After being jailed for three days in Chardon, Ohio, she was released, pending a court hearing which will determine whether she will be deported. The date of the hearing has not yet been set.

If she is deported, immigration officials have told her that her children, who are all American-born, will be placed in the foster-care system. Ms. Mendez has no other family in the United States.

“I’m very worried about what will happen to my children,” Ms. Mendez said. She has two boys, 16 and 9, and three girls, 7, 4 and 1. Their father, who is also an illegal immigrant, left the family more than one year ago. He hasn’t been heard from since.

One factor in Ms. Mendez’s favor is that she first came to the United States on a three-year work visa. When the visa expired, Ms. Mendez — who already had one child and another on the way — decided not to reapply, because she would have been required to return to Mexico first. There’s no guarantee that her visa would have been renewed, she said.

Ms. Mendez takes full responsibility for what led to her being arrested by immigration agents.

To support her children, Ms. Mendez works at a factory that makes parts for military airplanes. Because immigrants who aren’t living legally in the United States can’t obtain driver’s licenses, she was driving back and forth to work without one.

She was caught after being stopped for a minor traffic violation. When she couldn’t produce a license or other documentation, immigration officials were called.

Ms. Mendez admits that driving without a license was wrong, but says she had no choice. “I need to feed and take care of my children.”

“I’m the only provider,” Ms. Mendez said. “I have to work, even if it means driving without a license.”

Trying to help

Veronica Dahlberg, executive director of HOLA, which is in Ashtabula, Ohio, is trying to help keep Ms. Mendez in the country.

Ms. Dahlberg, who does not get paid for her work, has helped dozens of Ohio families avoid being deported.

“It is a long, difficult process,” Ms. Dahlberg admits. She works with immigration officials to find the most humane solution possible that takes into account the families’ welfare.

She also works closely with the affected families, introducing them to lawmakers and encouraging them to speak out about their plights to raise public awareness about the issue. “The main thing that we try to do is empower the families,” she said. “A lot of these people live their whole lives in fear.

“When immigration agents pick up people for deportation it’s done very aggressively. These incidents are very traumatic for families. We encourage them to become engaged in the democratic process so that they can try to improve their lives — which hopefully, will eventually help them on their path to citizenship.”

Contact Federico Martinez: at fmartinez@theblade.com or 419-724-6154.