MEMORIAL DAY

Black troops remembered for service to military

Veterans not honored during segregation

5/27/2013

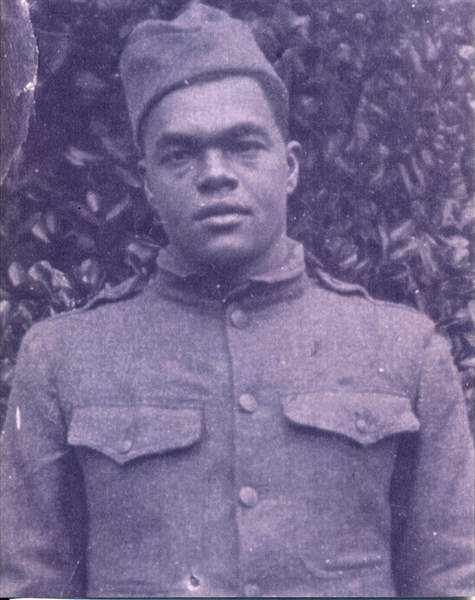

Homer Lee Quinn was a black soldier who served in a segregated black battalion during World War I. The battalion was one of four "experimental" black troops created to see if they were capable of serving in the military.

Homer Lee Quinn was a black soldier who served in a segregated black battalion during World War I. The battalion was one of four "experimental" black troops created to see if they were capable of serving in the military.

Most cooked and served meals to white soldiers. They dug ditches, cleared debris, cleaned latrines, and buried rotting corpses.

They served in segregated units, and were last to receive food, medicine, clothing, and other supplies needed to keep them alive. Those who weren’t killed during World War I faced the same discrimination and threat of lynching that existed before serving their country.

“A lot of people talk about how bad Vietnam veterans were treated when they returned,” David Eling, director of Military Affairs in west Michigan and a military history expert, said. “That was nothing compared to what black soldiers faced before desegregation. ... Even after desegregation, racism was still alive and well — it still is.”

The discrimination and humiliations they faced in the military weren’t the opportunities Homer Lee Quinn and the 340,000 other black soldiers were expecting or hoping for when they were drafted into the U.S. Army during World War I.

RELATED: Pulso Latino Blog: The Price of Freedom

Like Mr. Quinn, whose family and relatives settled in Toledo after the war, many black soldiers were hoping they would be treated with more dignity and offered better opportunities in the military.

That’s not what happened.

The accomplishments of black soldiers during World War I were downplayed, Mr. Eling said. They were hurriedly discharged from the military when the war was over and quickly forgotten.

“The thing is they have gone so long without being recognized,” Mr. Eling said. “The black soldier has always come to the forefront despite segregation.

“The Buffalo Soldiers, the Tuskegee Airmen, blacks have always distinguished themselves, but were rarely promoted to a branch outside of a black unit until the late 1940s.”

Most people know that the purpose of Memorial Day is to honor the memory of all the men and women who died while serving in the Armed Forces, Mr. Eling said. Hopefully, more people will start including those unheralded black soldiers who served just as honorably in World War I and World War II, he said.

Mr. Quinn officially began serving in the U.S. Army on July 29, 1918, during what was to become the closing months of the war, according to military records discovered by his family members.

He was assigned to the 340th “Lab” Battalion, Company B of the 34th, an all-black unit stationed in France.

There was a great deal of reluctance to allow blacks to serve in the military at that time, he said. Many southerners feared that blacks, so long abused and mistreated, would turn on white troops. Others questioned whether black people had the intelligence and courage to serve in the military.

There also were concerns that if black soldiers were successful, all blacks would begin demanding more rights and opportunities inside and outside of the military, Mr. Eling said.

To allay fears, black soldiers like Mr. Quinn were placed in segregated “labs” or units that were a social experiment to test whether blacks were capable of serving, Mr. Eling said. Black soldiers answered to white commanders.

The deck was stacked against the black soldiers from the beginning, Mr. Eling and other historians admit.

Black soldiers during WWI were forced to sleep outside in pitched tents during the cold, harsh winter months, according to an article written by Jami Bryan, managing editor for On Point, an Army Historical Foundation publication.

Those black soldiers who did see combat intentionally received poor training, Mr. Bryan said. Their successes were often publicly downplayed or credited to white soldiers. Their failures were trumpeted as proof of their incompetence and used as an excuse to boot blacks out of the military after the war.

Military records show between 5,000 and 7,000 black soldiers were killed during the war, although military officials acknowledge records for black soldiers weren’t well-maintained.

Many black soldiers died of diseases like meningitis. Mr. Quinn died of pneumonia on Feb. 4, 1919, during cleanup operations in France, according to the death certificate the military issued to his family. He was 32.

To this day, Mr. Quinn’s family believes his death could have been averted. Mr. Eling agrees.

“I guarantee you that if Mr. Quinn had been a white soldier he would have been treated or sent home and he would have lived,” Mr. Eling said. “I know people don’t like to hear that, but it’s true.”

Searching for truth

Like many black soldiers of that era, Mr. Quinn’s military service may have been forgotten forever if not for the efforts of his great-nephew, Anthony Quinn, 40, of Toledo.

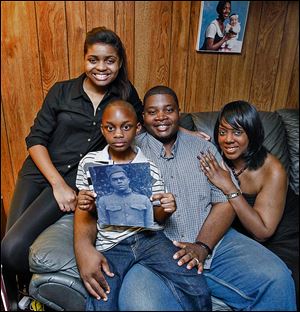

The Quinn family, from left Braniya, 15; Braylin, 7, and parents Anthony and Brandi, show a portrait of Homer Lee Quinn, Anthony's great uncle who died serving in the Army.

Anthony Quinn, who received a master’s degree in American history from Ohio State University in 1999, wrote his dissertation on “The Great Black Migration” of southerners to the north. During his research he met his great uncle’s ancestors, including many still living in Toledo, who shared with him photos and family stories.

Homer Quinn's parents were born into slavery, Anthony Quinn said. His uncle, the first of nine children, was born a free man in July, 1886, in Pinola, Miss., in Simpson County.

But Mr. Quinn, like the rest of his family, continued picking cotton on Mississippi plantations.

Anthony’s aunt, Velma Shoecraft, a lifelong Toledo resident, continues the story. Her father, Robert Quinn was Homer’s younger brother.

Back in those days there was a lot of tension between blacks and whites, especially in the South, Ms. Shoecraft, 88, said.

Frustrated black men were tired of the lynchings, they were tired of being denied the most basic of human rights, and they were starting to speak out. Outraged white men, just as determined to maintain their power and social status, used force and guns to try and maintain order.

It was a blistering hot summer day in Pinola when the Quinn brothers and a small group of other black plantation workers decided they’d had enough, Ms. Shoecraft says, recalling her father’s story. They hadn’t been receiving their promised wages; they had been verbally and physically abused. They confronted their employer.

There were accusations, threats, and shouts. Then the sounds of gunfire. Homer and Robert Quinn fled on horses.

“It was terrifying; we was all shooting,” Ms. Shoecraft recalls her father telling her when she was a child. “Bullets were flying over our heads. I thought we were going to die.”

A bounty was offered to anyone who could kill the Quinn brothers.

Unlikely allies

Their white grandfather, John William Quinn, a former slaveholder and former Confederate army sergeant helped sneak the brothers out of town late at night and hid them at his home in Boley, Okla., for a couple of years, Ms. Shoecraft said.

The Quinn brothers later rejoined their families in Sumner and Vance, Miss. In January, 1918, Homer married Sylvia Flemings of Louisiana and welcomed their only child, Vessie Lee Quinn, into the world in April.

“But Homer still dreamed of a better world,” a world that offered black people better opportunities and treated them with dignity and respect, his brother Robert Quinn would often tell his children. Homer believed serving in the military was a way to accomplish that goal.

After Homer Quinn died, it took the military more than one year to ship his body to the family.

“My daddy always told us, ‘that body wasn’t Homer’s,’” Ms. Shoecraft says.

Several years later, a French soldier who served with Homer, contacted Robert Quinn to tell him that his brother was buried in a French cemetery, Ms. Shoecraft said. Several family members eventually traveled to France to pay their respects. But the name and location of the cemetery has been lost with the deaths of the few family members who knew that information.

Two years after Homer's death, his wife, Sylvia, also died. Their 2-year-old daughter Vessie was raised by her grandparents, who moved to Toledo. When she was 22, Vessie Campbell died of tuberculosis while pregnant with her third child. Mother and unborn child died on the same date, Feb. 4, as Homer Lee Quinn had.

Vessie's surviving sons, Kenneth and Gordon Campell, were 4 and 2-years-old when their mother died. Kenneth Campbell, 76, who lives in Cleveland, says he barely remembers his mother. His brother, who lives in Chicago, has no recollection of her.

The Quinn family has a long tradition of passing along their history to younger generations. That tradition has been endangered in recent years as many of the older family members have died, Ms. Shoecraft said.

In past years, the large family would gather on Memorial Day to honor Homer Quinn and the other Quinns who followed in his footsteps and served in the military. But the family's ranks have thinned. Some relatives have moved away and others have died, Ms. Shoecraft said.

Anthony Quinn admits he didn’t know what to expect when he started exploring his family’s roots. It gave him his first opportunity to meet his father’s relatives, who embraced him with more love than he could have imagined.

A connoisseur of history, the research introduced him to a part of black history that he had never realized was so personal, he says. His goal now is simple.

“I want my children and other children to know about the sacrifices people like Homer Quinn made for us,” Anthony Quinn said. “It’s important to recognize the accomplishments of black soldiers in this country.”

Anthony Quinn was recently showing his 7-year-old son, Braylin, a photo of his great, great uncle. Young Braylin, noting that the picture was nearly 100-years-old, asked his father why anyone would be interested in doing a story about something that happened so long ago.

Father smiled at son.

“Because sometimes it takes that long to recognize the importance of what someone did,” Anthony Quinn said.

Contact Federico Martinez at: fmartinez@theblade.com or 419-724-6154.