Toxic algae could hit third of W. Lake Erie

NOAA says bloom to be heavy, but smaller than 2011’s dense growth

7/3/2013

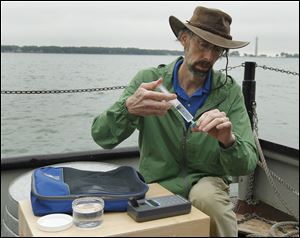

Dr. Rick Stumpf, of NOAA, demonstrates how to measure water samples with a fluorometer while on a boat in Lake Erie at Stone Laboratory on Put-in-Bay.

GIBRALTAR ISLAND, Ohio — Western Lake Erie is headed for another heavy bloom of toxic blue-green algae this summer that will damage the Great Lakes region’s recreation and tourism industries, threaten public health, and cost Toledo, Monroe, Port Clinton, and other area shoreline municipalities more to treat lake water for home and business use.

The western third of the lake can expect a “significant bloom” starting in early August. It likely will peak by mid-September, according to a new type of forecasting being developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

But the mass likely will amount to only about 20 percent of what it was in 2011, when dense mats of algae covered more of Lake Erie than it had in decades.

The highly anticipated 2013 forecast was outlined Tuesday by Rick Stumpf, a NOAA oceanographer from suburban Washington, at an event at Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory on Gibraltar Island, near Put-in-Bay, in front of 75 scientists, public officials, and journalists. Another 115 journalists and other listeners participated in an afternoon Internet presentation, a sign of how Lake Erie algae woes — a major research focus of U.S. and Canadian scientists since they re-emerged 18 years ago — are gaining a bigger audience. News stories about it have been carried in National Geographic, the New York Times, and other national publications this year.

Mr. Stumpf said the 2013 projection merely underscores how significant the problem was in 2011, when the bloom covered nearly two-thirds of Lake Erie. Large algae mats are normally confined to the warm, shallow western third of the lake.

This summer’s outbreak will most closely resemble that of 2003, he said, when it stayed in the western basin.

“People should pay attention. You need to plan to work around it,” Mr. Stumpf said.

Mr. Stumpf urged Ohioans to sign up for and frequently check back with this online NOAA bulletin: www.glerl.noaa.gov/res/Centers/HABS/lake_erie_hab/lake_erie_hab.html.

The algae problem has gained notoriety, not only because it has bloomed annually for so long, but also because of what it has meant to Lake Erie’s much-heralded recovery efforts.

Melinda Huntley, executive director of the Ohio Travel Association, said algae has the potential to paralyze tourism and recreation in eight northern Ohio counties that together have an $11.5 billion impact on the state’s economy.

Lake-based tourism and recreation support 117,000 full-time jobs, or 9.8 percent of the employment in those eight counties, she said.

“What’s at risk is a huge economic engine,” Ms. Huntley said.

Those expressing concerns about algae over the years have ranged from mom-and-pop motel operators to Cedar Point, one of Ohio’s largest employers.

The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency estimated several years ago that Toledo spends $3,000 or more a day on extra carbon-activated filtration to neutralize algae toxins in water it draws into its Collins Park Water Treatment Plant in Oregon, prior to customer distribution.

Algae has existed naturally in Lake Erie and other bodies of water around the world for thousands of years but usually not in such abundance. In 1995, after years of being suppressed, a toxic form of algae known as microcystis bloomed in western Lake Erie and has re-emerged almost annually.

Microcystis has the same toxin that killed dozens of people in Brazil nearly 20 years ago when it slipped through water-treatment and got into a kidney dialysis center. That resulted in a massive research project headed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and raised awareness of Lake Erie’s problem.

Algae tends to proliferate when water fed by the excessive nutrients warms. Much of Lake Erie’s nutrients come from phosphorus in farm runoff, sewage overflows, lawn fertilizers, and manure spills.

The NOAA-led forecast was done in western Lake Erie for the first time in the world last year, when scientists accurately predicted that 2012 would be a mild summer for algae. Last summer’s lack of algae was largely related to the region being part of the worst drought in the continental United States in 50 years.

Researchers at other agencies and institutions collaborate with NOAA on the forecasting, including Heidelberg University’s National Center for Water Quality Research in Tiffin.

Pete Richards, director of the Heidelberg-based center, said this year’s sampling of the Maumee River showed phosphorus levels in the water running slightly higher than normal. The Maumee, which runs through a mix of agriculture, residential, and industrial land, is the largest contributor of phosphorus to Lake Erie’s Maumee Bay.

The problem has prompted elected officials to consider tougher rules on agriculture for years. Some farmers have voluntarily acted or taken advantage of programs with government incentives to curb runoff, from leaving wider buffer strips on their land to planting windbreaks. Scotts, the world’s largest fertilizer manufacturer, has taken one of the largest corporate steps.

The company, based in Marysville, Ohio, this year removed phosphorus from its products.

In recent years, scientists have gone beyond simply looking at how much phosphorus gets in the water. One key, they said, is studying in detail how nutrients attach themselves at various soil depths and what it takes to keep them on land.

“It’s not so much the amount of agricultural runoff, but how [fertilizers are] being applied,” said Gail Hesse, Ohio Lake Erie Commission executive director and head of Ohio’s multiagency Lake Erie phosphorus task force.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com or 419-724-6079.