Sinkholes a risk, but Fla. shocker unlikely in Ohio

In Toledo, leaky water lines, not nature, are often at fault

8/17/2013

Workers assess the area of the sinkhole July 5, 2013 at the intersection West Bancroft Street and North Detroit Avenue in Toledo

THE BLADE/JEFFREY SMITH

Buy This Image

Workers assess the area of the sinkhole July 5, 2013 at the intersection West Bancroft Street and North Detroit Avenue in Toledo

This month’s dramatic collapse of a villa at the Summer Bay Resort in central Florida raises the question: Could a hole that big in the ground open up under a residential area here?

Anything’s possible, as Toledoans saw July 3 when a 19-foot-deep sinkhole opened up at busy Detroit Avenue and Bancroft Street, swallowing the sedan of Pamela Knox, 60, of Toledo as she was driving. She was not seriously hurt.

A week later, an East Toledo resident, Karen Cox, received a minor foot injury after slipping into a smaller, yet still troublesome 5-foot-deep hole that opened up on her property on Nevada Street.

If it’s any consolation, most Toledo-area sinkholes aren’t natural.

They’re usually the result of leaky water and sewer lines.

“That’s a really important distinction to make,” said Ann Tihansky, a U.S. Geological Survey geologist and hydrologist in Washington who has spent years studying sinkholes.

“We have infrastructure that needs maintenance and repair.”

Larger and more frequent sinkholes that occur naturally are most often a result of dissolved limestone or dolostone. Other types of dissolvable bedrock include gypsum and salt.

Florida is the prime location for them, although that scenario also gets played out in other states with conducive geologic features — even scattered parts of Ohio, especially the Bellevue area. In eastern Ohio, sinkholes also can form when abandoned mines collapse.

Excessive water usage can cause sinkholes too.

In 2010, more than 100 sinkholes were formed in central Florida when farmers pumped water to stave off damage from a crop freeze, Ms. Tihansky said.

“It caused the water-management district to re-examine how it issues permits,” she said. “We pushed the boundaries.”

Distinctions between various causes of sinkholes may not mean much, though, given that people can get just as injured falling into a deep hole created by a busted water main as one created by the natural cave-in of surface land.

But knowing the basic geological differences between Ohio and Florida could help allay some fears about the kind of massive, 100-foot sinkhole that formed without warning early this week beneath the Summer Bay Resort near Clermont, Fla.

Nearly a third of a villa collapsed into the hole, which began forming Sunday night and continued opening up into the following day.

Miraculously, no one was injured. But the case was the latest reminder of how unpredictable sinkholes are — and how they can induce shots of adrenaline and jolts of panic, even if nobody gets hurt.

Florida is not the only state where naturally occurring sinkholes occur.

But it gets a lot of attention because nearly all of Florida has several thousand feet of limestone right below its surface. The state’s rapid growth, which has led to excessive water withdrawals, has made land there more unstable.

What lies beneath

Limestone is a type of bedrock that gradually dissolves over many years, as rain penetrates the surface soil and ground water becomes slightly acidic.

As the limestone dissolves, the surface land loses it support. The land’s stability is further compromised as Florida’s demand for water increases, and its aquifers become more depleted.

About 97 percent of Ohio has a natural buffer to protect against the same type of sinkholes forming, although there are no guarantees, said Douglas Aden, an Ohio Department of Natural Resources geologist.

Glacial activity thousands of years ago deposited 30 or more feet of sand, gravel, and clay over Ohio’s more vulnerable layers of bedrock.

“If there’s more than 25 feet of it, that tends to shield the bedrock because it’s really just buried then,” Mr. Aden said.

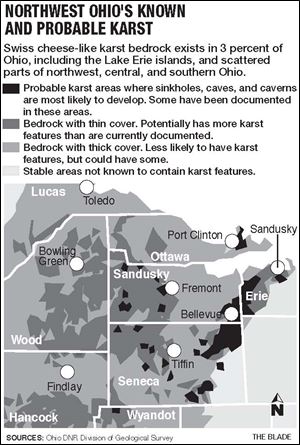

In Toledo, there are 150 to 200 feet of glacial deposits buffering vulnerable bedrock, said Richard Pavey, an Ohio Department of Natural Resources geologist. About 3 percent of the state has Karst geology near its surface, characterized by porous, Swiss cheeselike formations.

“Florida has almost 100 percent Karst bedrock,” Mr. Aden said.

About 20 percent of America is underlain by Karst geology, according to Randall Orndorff, a U.S. Geological Survey geologist.

Karst, which includes limestone and other types of bedrock that can dissolve, is in portions of northeastern Seneca County, northwestern Huron County, southeastern Sandusky County, western Erie County, and portions of Ottawa County, including the Marblehead Peninsula and the Lake Erie islands. Karst bedrock also can be found in parts of central Ohio, especially Delaware County, and parts of southern Ohio, Mr. Aden said.

“Risk is related to where you are in the state,” he said.

Frequency

There are myths and misnomers about sinkholes, one of which is the general belief they are on the rise. The oil and gas industry’s plans for more hydraulic fracturing of shale bedrock, a process known as “fracking,” has drawn more attention to the general issue of sinkholes nationally.

But in Florida, it’s unclear if there have actually been more sinkholes or just more insurance claims.

Since 1981, the year Florida had its largest cave-in in terms of property loss, sinkhole-related claims have risen because of changes in that state’s insurance laws and its population growth, according to a paper published by Clint Kromhout, a Florida Geological Survey geologist.

“From a public perspective, sinkholes seem to be occurring more frequently in Florida,” the paper states. But it said sinkholes “are likely forming at the same rate they always have in Florida.”

The potential danger should not be underestimated, however.

On Feb. 28, a sinkhole that opened up at about 11 p.m. under a house in Seffner, Fla., swallowed the entire bedroom where Jeffrey Bush had been sleeping. His body was never recovered.

Trouble elsewhere

Florida leads the nation in sinkhole activity but hardly has a monopoly on the most dramatic.

A year ago this month, 350 residents of Bayou Corne, La., were evacuated following the collapse of a salt dome cavern operated by a petrochemical company, Texas Brine LLC — an example of a major sinkhole potentially caused by mankind’s activity.

In a recent Associated Press article, Houston-based Texas Brine was said to have been drilling on the edge of a salt dome in order to create a cavern so it could extract brine for refining processes.

The article quoted scientists as saying the underground storage cavern was being mined too close to the edge of the salt dome and caused the sinkhole.

Louisiana this month filed a lawsuit against the company and its principal owner, Occidental Chemical Corp., for damages from that event, which resulted in a massive, 24-acre sinkhole in a swampy area 40 miles south of Baton Rouge.

Geologists who focus on natural sinkholes struggle with identifying where the next ones will be.

The Florida Geological Survey, part of that state’s Department of Environmental Protection, is trying to develop a better tool for diagnosing the most vulnerable areas but does not make any claims that it is predicting where sinkholes will happen next.

“It’s definitely not predictable,” Ms. Tihansky said. “I think there’s going to be a certain number of sinkholes no matter what we do.”

A common denominator seems to be stress on the land, whether it’s growth and development patterns, failing water and sewer lines, or industrial activity such as mining and drilling.

Climate change could exacerbate the problem, regardless of whether a region endures a severe drought like the one in 2012 or gets deluged by rain, Ms. Tihansky said.

“Any time you introduce an environmental extreme, you are likely to see a change in the landscape,” she said.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com or 419-724-6079.