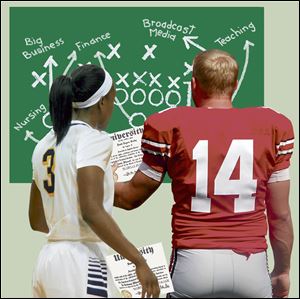

After the game: Athletes wise to prepare for life away from sports

4/20/2014

Only 0.5 percent of NCAA Division I athletes continue playing in professionals sports.

When DeMark Jenkins’ sophomore season with the Bowling Green State University football team ended prematurely because of an injury, he finally asked himself something that he had never asked himself before:

What would you do if football ended tomorrow?

Nearly five years later, Jenkins admitted that nobody had ever asked it of him before, either.

He broke his arm during the fourth quarter of a loss at Marshall in September, 2009, and the injury forced him to do some reflection.

“It hit me: I’m no longer here just to play football,” recalled Jenkins, a 2012 Bowling Green graduate. “I realized that this all could be over at any time, and that football was temporary.”

Jenkins needed to evolve, not just as an athlete but also as an individual. It meant preparing himself to be a professional. He knew he had a passion for helping people who were like him, and he pursued opportunities in volunteering and interned at the United Way of Wood County before earning his first job after graduation as a development officer and volunteer coordinator with the United Way of Greater Toledo.

Jenkins is now a donor relations associate with the United Way of Central Indiana but after he was injured, Jenkins thought back to something that was written each year on Bowling Green’s football playbooks: “Everyone has a plan until something happens.”

NCAA Division I colleges invest in their athletes to prepare them competitively and academically — to make the grade both on the playing field and in the classroom.

But there’s another facet that comes into play: completing degree requirements to move into the work force. For those who don’t become professional athletes or coaches, they must find a job outside of sports.

They may face a disadvantage in not having enough or any pre-professional experience. They may have devoted too much time to major college athletics and merely completing their degree, and not enough time to academic and career development.. Their resume may be short or, even worse, blank. Or they may not be able to navigate the work force and the interview process. They may not be able to shed their identity as an athlete — one that has defined them for years.

“In terms of a career, there’s a lot of athletes who, when they get to college, their first goal is to go to the next level, to the NFL,” said Peter Winovich, a former BG football player who is a financial adviser with Wilcox Financial in Toledo. “I didn’t have the opportunity to do that and I knew that, early, that I wasn’t going to be able to do that with my athletic ability.

"I had to prepare myself for other opportunities. One thing with athletes is the need to find your identity and transition it into your next career.”

The onus is also on an academic institution to help those athletes develop a career path — in something other than professional sports. The NCAA in 2011 pegged the number of student-athletes who move on to professional sports at 0.5 percent of its 400,000 student-athletes. In 1991, the NCAA Foundation developed the Student-Athlete Affairs program, which emphasizes athletics, academics, personal development, community service, and career development. That philosophy is implemented at colleges and universities in the form of career planning and development programs. Yet career service and development programs for college student-athletes typically do not keep data on job placement.

“You have to ask, what are you doing on a programmatic level to build the professional development of a student or a student-athlete?” said Dan Lebowitz, executive director of the Northeastern Center for Sport in Society, a Boston-based think tank that examines sociological issues in the realm of athletics. “How is your institution taking data and testimonials to build upon this?”

Programs to help

Lebowitz offered Northeastern’s cooperative education program as an example — students spend at least two semesters of college in full-time jobs that are relevant to their major or the career they plan to pursue. Even that comes with a quandary: being a Division I athlete these days is akin to holding a full-time job, complete with certain academic expectations.

“That arena still needs help,” Lebowitz said.

Shari Acho is the director of career education and advancement for Michigan’s Professional and Career Transition (M-PACT) program, which helps Michigan’s student-athletes with career planning or post-graduate endeavors.

“The NCAA and universities have spent millions of dollars to make sure student-athletes would graduate,” said Acho, a former UM academic counselor who established M-PACT four years ago. “The problem now is that we’re graduating students, but it’s not enough. What I’ve seen or have seen in the past is that kids just take jobs. They just find something, and they weren’t intentional about anything.”

HBO’s Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel aired a segment in March on academic reform in college athletics and interviewed Bryon Bishop, a former North Carolina football player. Bishop acknowledged that he was told to take courses in one major — “to stay on course for graduation” and also acknowledged the lack of career preparation he received while at UNC. He told HBO that he works in a low-skill job at a drug treatment facility.

HBO also interviewed Erik Mensik, an offensive tackle at Oklahoma, who graduated in 2010 with a degree in multidisciplinary studies and said that when a prospective employer asked what his major was, he merely explained that “it was a lot of classes.” HBO reported that Mensik worked as a handyman and now has an office job.

“You can’t see the things that are going on in the system until it’s too late,” Bishop told HBO. “I’m pretty much facing that now, the reality. I ask myself, what did I really get from the school?”

Acho sees her program — which runs the gamut from writing a resume to preparing to apply to medical school — as a vessel to connect student-athletes with their passions, and with what many term as “the real world.”

“It’s our responsibility to help these students,” Acho said. “You have to look at every student-athlete and uncover what it is they want to do.”

Bowling Green’s student-athlete services office requires freshmen student-athletes to register for a first-year seminar in which career exploration is part of the curriculum.

“For some of them, it might confirm that, yes, I want to be a nurse, or I want to be in sports management,” said Kerry Jones, BG’s director of student-athlete services. “It’s really helpful in giving them the options that they may want, or that they may not want.”

One of the first things Jones and her staff ask incoming student-athletes to do? Write a resume.

“That resume, when they come in the door, is mostly made up of what they’ve done in sports,” Jones said. “Most of them have never had a job, or a lot of them have had part-time jobs. We talk to them about tailoring their resume and we ask them, ‘Do you have leadership opportunities? Did you work in a clinic? What kind of work do you have with children or young adults?’ ”

At the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Success Training and Exit Planning for Seniors program is the culmination of a leadership program that the school offers for its student athletes. The program partners with the school’s career services program and works with student-athletes, from those who know what their major and career plan will be to those who come to Colorado with no idea what to do.

“There’s a lot of research that shows that a college athlete, whether they’re at Division I, II, or III, identify themselves as athletes and have their whole lives,” said Dave Callan, director of student-athlete leadership at Colorado. “When they leave their sport at the college level and most don’t turn pro, that identity becomes an identity problem for some. What do they do with that?

“Programs like this have been designed to help that. The [United States Olympic Committee] has one for life after being an Olympian. You have to ask, how do you help a person find their identity?”

Managing time

In the last 20 years in college athletics, Lebowitz said the biggest improvement he’s seen is in the emphasis of academic support — given the importance of eligibility and the monitoring of graduation rates among college athletes.

“It’s a very good concept because you just can’t look at athletes as part of a model of indentured servitude,” Lebowitz said. “You have to look at the full person. When you look at an athlete, wouldn’t it be best to look at the logic of their development? How do you make an athlete academically sound, ready for the work world and developed socially?”

As he recovered from his injury, Jenkins began volunteering in the Bowling Green area and became involved with his fraternity, Phi Beta Sigma. He learned to polish himself and attended job fairs, where he spoke with representatives from health and human services organizations in Lucas and Wood counties. He eventually began an internship with the United Way of Wood County, which became a full-time job after graduation.

Yet as Jenkins tried to balance being a football player at Bowling Green and preparing for a career, he found himself in a quandary.

“For every minute I used to take to try to develop myself as a professional, I felt like I almost didn’t want to do it because I was taking a minute away from being a better football player,” said Jenkins, who received his degree in human development and family studies. “I’d think, ‘I could be watching film, or I could be in the weight room.’ Why was that my motive?”

Callan said the biggest problem he has confronted is helping student-athletes at Colorado obtain work experience, especially in the engineering field. Most internships, he explained, are 40-hour work weeks and fall in the summer — at the same time athletes are training full-time.

That means opting for a 20-hour-a-week internship rather than 40 hours, or calling upon a Colorado graduate or a former letterwinner who may be able to facilitate work experience that helps meet a student-athlete’s needs or requirements.

Time, Acho said, is the biggest limitation for a student-athlete. With training, travel, and classroom requirements, major college athletics has become a year-round endeavor.

“The dynamics have changed so much over the last few years,” Acho said. “But that’s why they need help. And you can’t use it as an excuse, either. There’s summer, spring, and there’s a few more hours in the offseason. We want to work with them and offer to help them.”

School responsibility

Jenkins believes there’s room for growth when it comes to developing student-athletes on a holistic level, not just on an athletic or systematic plane.

“It would help if we had more in place to focus on young men and women as students and not just as athletes,” Jenkins said. “Being productive as an athlete is a priority and you are held to a standard. If you’re held to a standard in the classroom, you can create professionals. But you have to ask, are we taking time to teach student-athletes? Find out what their passion is instead of just creating a journey for them.

“If things are implemented that can help us find this out earlier rather than later, it can help the athletes realize this sooner. Find a way to develop ourselves as people.”

For the investment that a university makes in its student-athletes — and for the full investment that students make in earning a college education — Lebowitz asks a rhetorical question of the process.

“Isn’t it the responsibility of a place such as a university to make you successful?” he asked. “And isn’t it inherent to provide for your students and student-athletes in order to ensure that success?”

Callan, the Colorado administrator, answers in the affirmative.

“As a university, we give them scholarships and put them on teams based on who they are,” he said. “It is our responsibility to prepare them for life when they are not a part of that anymore. That happens when they leave us.

“Do we have an obligation to do this? Yes.”

Contact Rachel Lenzi at: rlenzi@theblade.com, 419-724-6510, or on Twitter @RLenziBlade.