THE UGLY TRUTH ABOUT TOLEDO

Baltimore’s fight against blight could offer guidance to Toledo

6/29/2014

People wait for the bus in front of an empty building at North Howard and West Lafayette streets in West Baltimore. The key to improving downtrodden areas of the city, many say, is community involvment and spending money wisely.

THE BLADE/AMY E. VOIGT

Buy This Image

A youth rides a bicycle past a blighted property that will be restored by Come Home Baltimore. The run-down unit is sandwiched between renovated properties on North Bond Street in Baltimore’s Oliver neighborhood.

BALTIMORE — Death threats did not deter Earl Johnson.

“Those threats just strengthened my resolve to make changes. I wasn’t scared of getting my head cut off or shot off, but I was scared of something happening to my wife. If something had happened to her because I didn’t get involved, I couldn’t have lived with myself,” Mr. Johnson said.

He stepped up and then got down and dirty. Hundreds of others in Baltimore did the same.

PHOTO GALLERY: Click here to view slideshow

RELATED: Blight afflicts many U.S. cities

RELATED: The Ugly Truth About Toledo series

RELATED CONTENT: East Baltimore crime data

Weary of worrisome dangers and destruction, the take-back-Baltimore movement has helped heal sections of the city wounded by caustic conditions.

Blight was kicked to the curb in the Oliver neighborhood in particular. Call it a modern-day Oliver twist.

In 2010, Oliver was a pitiful place. Plywood, not glass, covered windows of most homes. Vacant and abandoned, the blighted neighborhood was a filming location for the Baltimore-based HBO drama The Wire.

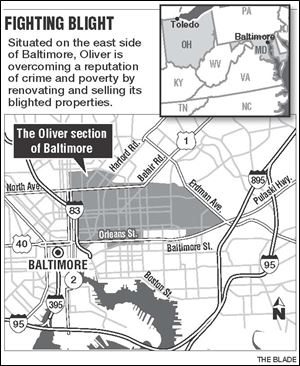

Situated on the east side of Baltimore, the neighborhood was a victim of lead-paint laws, racial riots, the introduction of crack and heroin, and white and black flight, said Mr. Johnson, 33, a leader in the Oliver community who is also a member of Baltimore’s Commission on Sustainability. “Whoever could leave left town. People who could not leave were house poor. They did not have money to repair their houses.”

Slum settled in.

Today, however, ruffled lettuce leaves crop up in the community where gun blasts once pelted the mean streets with homicidal horrors.

Row houses, renovated inside and out, have been purchased by people who want to live here. Residents walk their dogs at dusk. Neighbors sit on front porches. They mingle. They watch out for each other.

As in other communities across the country, including Toledo, the blight problem was years in the making. Fixing it? It’s not like making Minute Rice or cooking a pot of instant oatmeal or scratching with a coin at a lottery ticket.

Earl Johnson, the executive director of Come Home Baltimore, says death threats have ‘only strengthened my resolve to make changes’ to improve his hometown. Change, he says, starts with citizens.

Taking responsibility

Change, Mr. Johnson said, starts with the residents. It’s about citizenship, not about hope. It’s about setting dreams into motion and anchoring a new reality in place. “No sacrifice, no victory, that’s what I say. There is a price to pay for being an American.”

“Sometimes things get messed up. Sometimes the streets get overrun with problems. The government always can’t help. At the very least, people have to do their part. You have to take responsibility for your place. Interject yourself in your community. No change is going to happen until your citizens decide it’s going to change. And if you don’t change, neighborhoods are like prisons. Nobody comes out to sit on their front steps anymore,” Mr. Johnson said. “Community work is ugly and stressful. It is not about people holding hands and swaying side to side while singing ‘We Are The World.’”

His goal is to take the successes of Oliver to other portions of Baltimore and to other cities. With a smile, he said, “We can’t keep all the goodness to ourselves. Others are hurting too.”

He’s seen tough times himself and has had some run-ins with police. That seems to connect some people, in trouble and trying to turn things around, to him.

New, slick phone apps have been introduced to report blight problems and to keep track of progress in addressing those issues, Mr. Johnson said. Residents can track problem properties online on the city’s Web site that includes details on various creative programs to engage residents in community issues.

Mr. Johnson is executive director of Come Home Baltimore, a for-profit firm that works to renovate homes and encourage people to move to the Maryland city. The firm was created by David Borinsky, a former lawyer who is now an investor and developer. He too is rooting for the return of safe and populated neighborhoods where the bleakness of blight clouds the future.

Cleaning up

From the front seat of her taxi, Venus Ryan sees the city through a windshield and hears the stories from the backseat. “Been driving since 1999. I love it.” Baltimore has had its ups, its downs, she said.

A mural by Operation Oliver adds a splash of art to a neighborhood once known for vacant homes, poverty, and crime. From 2002 to 2008, the Oliver neighborhood of Baltimore was the filming location for the gritty HBO drama ‘The Wire.’

She rattled off lists of the “good guys” — firefighters, police officers, city officials who care — and she knows the good places that plate good eats — fried chicken, collard greens, fresh fruit, fresh meats.

She feels safe, even in a city with “lots of addicts.”

“I have never been robbed in my whole life. Never.” A native of Baltimore, she notices improvements. “But they gotta clean up more.” And by cleaning up, she means the drug trade.

It’s gotten so bad, she said, that some businesses are literally putting the heat on drug dealers — and putting them in the deep freeze too. Stores, she said, jack up the thermostat — it makes it feel like three ovens blasting — in restrooms in the summer to keep drug dealers from sleeping or conducting drug deals there. In the winter, icy cold restrooms chill out the drug deal, she said.

As she drives, she polishes, buffs, and manicures her nails. Polite and pretty, she keeps herself and her clients safe by following her own rules: She refuses to pick up, or drop off, clients in some areas of the city, such as places that have reputations for being “littered with bodies” of drug addicts who die of overdoses in abandoned buildings.

Several Baltimore residents said people are not looking for a handout, but rather a hand up, and when that happens, so does change. Real change. Not the happy feel nonprofits get when money is handed out for murals and green-space lots and community gardens, some said.

Oliver does feature a community farm, bursting with a sea of greens. A hoop house keeps the growing season going beyond a couple months. Rows of tomatoes, squash, peppers, kale, mustard greens, and other vegetables pop color in what had been, as residents described it, a war zone. “It was like Beirut,” one said.

High crime was a deadly problem, and most assuredly a summer salad from a community garden didn’t knife apart criminal elements.

It will take more, much more to turn neighborhoods completely around, Mr. Johnson said. Dollars spent wisely is key. Spend money to buy someone an air conditioner rather than buy yet another flat of flowers or a can of paint.

“Murals and gardens will never save Baltimore."

What are needed are stick-like-glue projects and programs, not feel-good one-day-in-one-day-out efforts such as college kids coming in for a day to pick up trash or a batch of one-holiday do-gooders serving turkey, taters, and gravy to the homeless on Thanksgiving.

A comeback

Colin Lyman, 24, who works at the Oliver Community Farm, volunteers his time for the neighborhood’s improvements. Why? “Because no one else was doing anything. Now they are. I’d like to think we are making changes and making a difference where people live now. It used to be all boarded up and now look at it.”

Niklas Rahkonen, who is in town for business from Los Angeles, takes a photograph of his wife, Dharma, and his 7-year-old son Eilan in front of the water in the highly visited Inner Harbor area of Baltimore.

Baltimore is making a comeback, and “I would never leave here. Baltimore is my home,” declared Quintin Harris, 53, who lives on the outskirts of the inner city. He loves to sample the fresh fruits and produce available from the local farm and the weekly farmers’ market. He has been in the home-restoration business for 37 years. Lately, business has been booming.

He recommends continuing to demolish houses that are in deplorable condition. “Donate the lots to the next-door neighbors. People need more space and that is happening and that is a good thing.”

He also would like to see more houses saved, places worthy of renovation. “A lot of homeless could use those houses for their living arrangements. We need more jobs. People want to work. Baltimore is a city of good people, beautiful loving people. They say they want to volunteer. Give them a chance to do that. Volunteers learn values, morals, discipline, respect. We need to teach that to kids, to 7-to-10-year-olds. Then they will support our city. The kids, they are our future, and that is so precious to Baltimore.”

City of contrasts

Baltimore is a city of contrasts. Towering buildings soar in the city’s skyline. On street level, empty buildings sour several areas.

Gone are many businesses, replaced by boarded up windows. Other windows are shattered or cracked.

On North Howard Street, a sad scene: Hundreds of pigeon feathers scatter behind cracked glass in one building. Pigeons flutter in, perhaps through a hole in the roof, and then, in desperation to return outdoors, beat themselves against the window in a feathery panic. One dead pigeon, belly up, is stripped bare, its bony carcass symbolic of the dreadful street scenes in blighted areas.

Nearby, nearly an entire block is shut down. Customers no longer bustle from the building with boxes under their arms, happily heading home with their purchases at the Hutzler Brothers department store in the 200 block of North Howard. Faces in stone stare down at passers-by. The building has been closed for years, residents said.

Some service businesses seem to prosper, places where you can get your nails polished, your hair done. You can walk in and buy phone cards or pawn a wedding ring. Lawyers, tax accountants, bail bondsmen. They work here.

Such businesses handle problems related to lawbreakers, said Sherry Bost who called Baltimore “depressing.”

“Drugs have taken over the streets. Drug dealers come down here to sell their little dope bags, sell their little crack, sell their little pills,” said Ms. Bost, 54, who has a biblical studies degree and is working on a bachelor’s of science degree. As she talked, she gobbled down crab sticks, licking fingers to savor the sauce. “It’s all I could afford,” she said about the small bag containing more of a snack than a meal.

People wait for the bus in front of an empty building at North Howard and West Lafayette streets in West Baltimore. The key to improving downtrodden areas of the city, many say, is community involvment and spending money wisely.

As she talked, numerous people stumbled around the streets, asking for 70 cents for bus fare, a buck for a cup of coffee. A job. Can you get me a job? some ask.

She ignores them or shoos them away. Hard to ignore the elderly man who wandered a parking lot, trying to figure out how to step a few inches over chains attached to yellow posts. “[Addicts] come down here to get their meth,” she said, referring to a nearby methadone clinic. “Then they come to the streets and get pills to enhance the meth. You weeble, you wobble, and try not to fall down.”

She can relate. “I lived it. I was hooked on drugs.” Now, Ms. Bost wants to provide an outreach program for homeless women addicted to drugs. “They have to be sincere about wanting help, about getting off drugs. I have a counseling license. I know I can help.”

High school drop-out rates in Baltimore are high. “Parents do not care if their kids go to school or not. I think we should be more strict on the parents,” Ms. Bost said. “When kids break curfew, fine the parents $500. That would be a wake-up call to them.”

She’s tired of people saying that residents should get a pass because they had a tough upbringing. “Stop making excuses for them. We can make a difference by being stern with them. Don’t let them run over you. You can’t be passive with some people. We need to teach them a better way. We need to teach them if you break laws, you lose your job. We need to teach them to be respectful of their peers. Teach them to give the same courtesy to others that they want to receive for themselves. People can rise above it.”

Lordy, she said, Baltimore needs help. “I’m glad that the mayor said she is going to enforce a 9 p.m. curfew starting in two months. That is an excellent idea.”

Others disagreed, saying a curfew will tick off teens rather than encourage a cooperative spirit in them and the community.

Venus Ryan, a Baltimore cab driver since 1999, often works the night shift in blighted and crime-ridden areas of the city. She refuses to pick up or drop off clients in some of the worst areas of the city. A native of Baltimore, Ms. Ryan acknowledges recent improvements. ‘But they gotta clean up more,’ she says.

Several Baltimore natives love the city in spite of issues, and they point out that the city flourishes in many areas, including the magnificent Inner Harbor as well as the many tourist sites tied to the city’s storied past. There are oodles of opportunities to take part in arts and culture. And the architecture on century-old buildings inspire awe at the craftsmanship.

And Toledo, even though blighted in some neighborhoods, of course also has its beauty and its gems, some world-renowned: the art museum, the zoo, the Mud Hens and the Walleye, and much else to boast about.

Tips for Toledo

Baltimore residents are quick to offer tips to Toledoans who want to rid the Lucas County city of blight, or if not rid it, at least reduce it: Pick up the phone. Just do it. Call police when you see a crime. Call authorities when the grass gets tall, when rats scurry from boarded up houses to your property. The city’s Web site is user friendly when it comes to nuisance abatement and blight reduction programs and project details.

Perhaps, Baltimore residents suggested, Toledo could review successful programs and consider adopting them for the Glass City’s blight that has been detailed in The Blade’s series, The Ugly Truth About Toledo.

However, note too: Success stories are being scratched out with sticks, scrawling letters in shifting sand.

Ongoing efforts

Concrete change isn’t yet a certainty, including in Oliver. Challenges continue: Get the community involved on a permanent basis, get jobs for those who truly want to work, encourage people to value their properties and care about their neighborhoods, Mr. Johnson said.

But at least revamped row houses in the Oliver area are creating a buzz, and home buyers are starting to put out brand new welcome mats as the rebirth catches hold.

A banner advertises the sale of a blighted home that will be renovated by the Come Home Baltimore program. The firm advertises luxurious, energy-efficient homes.

Programs to promote neighborhoods include stepUP! Baltimore, designed to connect individuals, groups, and communities to volunteer together to change these areas — multiplying and channeling their energy and ensuring that everyone can participate in making Baltimore better, safer, and stronger.

In her online message about stepUP!Baltimore, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, who was sworn in as Baltimore’s 49th mayor in February, 2010, said many Baltimore residents already have stepped up.

“I believe Baltimore is filled with agents for change. In each person and in every corner of our city, from the least to the most likely of places, we are the agents of change. We are the ones who give back, who help, who volunteer. Together, we can make our city better, safer and stronger. stepUP! Baltimore will do that through impact volunteering, creating a ripple in a few places that over time can become a real tide of change.”

April Nicole Gladney is pleased by the changes in the Oliver neighborhood. “My grandchildren can play outside now. I can be outside with them. It makes us feel like a family again.” She frets, though. She needs a job. “I make do, but I want to work,” she said.

Real change will happen when she hears the happy sound of music from an ice cream truck and she can wave at the driver to stop. These days, the truck passes on by. “I am tired of having no ice cream money to treat my grandkids. I want to earn some money. Baltimore is a big, bright, beautiful community.”

Opportunities are starting to happen, she said. “Someday, that truck will come by and I will have money for ice cream. I know it, I just know it.”

Contact Janet Romaker at: jromaker@theblade.com or 419-724-6006.