U.S. gave Chesapeake Bay billions for impaired waters: Is Lake Erie next?

11/17/2016

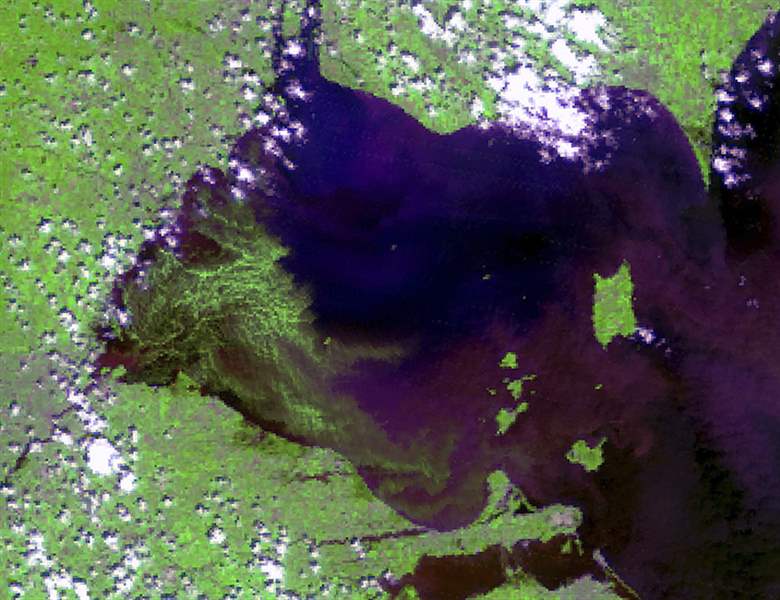

Lake Erie algae dense scum as shown in August, 2015.

NOAA

Pressure by federal officials six years ago to save the ailing Chesapeake Bay has prompted 11 federal agencies to invest $2.84 billion into that ecosystem, including $515 million last year and $487 million this year.

That effort has generated some mind-bending dollar signs.

But many people remain confused over what parallels exist between the Chesapeake Bay and the western Lake Erie watersheds — and if this region is being foolhardy by not following suit over designating the western Lake Erie watershed as impaired.

Designating a watershed as impaired is a first step toward getting a federal program established that greatly restricts how algae-forming soil nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus can be used on area farms.

Known as a TMDL, an abbreviation for Total Maximum Daily Load of pollutants, such a program is far more precise and site-specific than the hodgepodge of traditional state-by-state rules.

The Chesapeake Bay is the nation’s largest.

The program, which went into effect on Dec. 29, 2010, involves a 64,000-square-mile watershed that spans New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia.

It wasn’t mentioned by name as a TMDL when President Obama issued an executive order in May, 2009, that called for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to step in.

At that time, with the help of several other federal agencies, the federal EPA formed a federal leadership committee that would be at the helm of “a renewed commitment” to controlling pollution from all sources.

The state of Ohio has multiple TMDLs for small bodies of water.

But even with Michigan’s impairment designation for its small part of western Lake Erie last week, Ohio officials remain steadfastly opposed to doing the same.

According to U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo), Vice President-elect Mike Pence has told her office he has no interest in using his position as Indiana governor to get the Hoosier State on board.

He has gone so far as to deny there’s enough scientific evidence to prove northeast Indiana farms have an impact on western Lake Erie’s water quality — resistance that Miss Kaptur said she views as stunning.

To many people, one of the selling points of a big, regional TMDL — such as one that would include Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana — is its potential to provide more leverage for federal funding.

They work off the theory the government is more apt to invest in regions that are unified for a common goal that ones with fragmented policies.

But even some public officials as liberal as U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D., Ohio) warn that embracing the TMDL process offers no guarantees for additional federal funding.

According to a statement on Page 17 of a Sept. 21, 2012, Congressional Research Service report, the federal Clean Water Act “provides no dedicated funding for TMDL development or for implementation.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Brown’s office said the senator would continue to seek money for Lake Erie restoration efforts through the federal Farm Bill, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund.

The latter two are programs used to fund much of the nation’s water infrastructure, such as upgrades to sewage systems and water-treatment plants.

Miss Kaptur, who supports calls for the impairment status, began a lengthy interview about the TMDL program by saying it’s important for people to realize the process of how government customarily works.

The U.S. EPA spends an inordinate amount of its budget defending itself in court, both from critics who accuse it of going too far with regulations and from activist groups that believe it has fallen short when enforcing portions of the Clean Water Act.

The state of Ohio could save taxpayers some money and help the U.S. EPA have more money for Lake Erie by designating the lake as impaired, she said.

“The state of Ohio has to do its job. It hasn’t done enough to address challenges,” Miss Kaptur said.

She said Ohio is “like an absentee father” on Lake Erie issues.

“There’s a state responsibility here that is very haphazard, very hit-or-miss,” Miss Kaptur said. “They’re risking our future. This won’t happen by magic.”

Karl Gebhardt, an Ohio EPA supervisor who represents Ohio Gov. John Kasich’s administration on Lake Erie issues, said he takes exception to Miss Kaptur’s remarks.

He believes the administration has Lake Erie on a path toward recovery without embracing the TMDL program.

“In practice, we’re already doing some of the things they’re doing over in the Chesapeake Bay,” Mr. Gebhardt said.

In addition to passing through millions of federal dollars for sewage and water-treatment programs, the Kasich administration — at the request of Ohio Sen. Randy Gardner (R., Bowling Green) — committed much of a $10 million allocation toward a North Toledo research project that aims to help phase out open-lake disposal of dredged material.

That occurred in July, 2014, a month before Toledo’s high-profile water crisis.

Last March, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service announced it was making another $41 million available over three years to help farmers reduce algae-forming runoff into western Lake Erie.

That funding brought the total commitment for the program to more than $77 million, more than twice what was previously budgeted.

That program, Mr. Gebhardt said, is just one example of innumerable dollars coming into the Buckeye State since nearly 500,000 metro Toledo residents were forced to go without their own tap water the first weekend of August, 2014, instead relying on bottled water and emergency distributions from the Ohio National Guard.

“We need a better system to track what money’s coming into Ohio, who’s getting it, and what the results are,” Mr. Gebhardt said. “Until we get a better system in place, I’m not sure we need more money.”

He called Ohio a leader in a collaborative effort to reduce runoff by 40 percent, an effort that has included Ontario.

“I think it takes a lot more than just throwing money at this issue,” Mr. Gebhardt said.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com, 419-724-6079, or via Twitter @ecowriterohio.