SOUTHERN REVIVAL

Rights fight goes on in new location

Rev. Floyd Rose can’t stop helping

2/6/2017

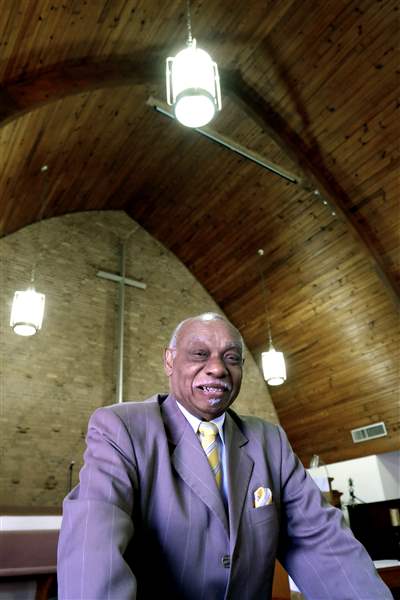

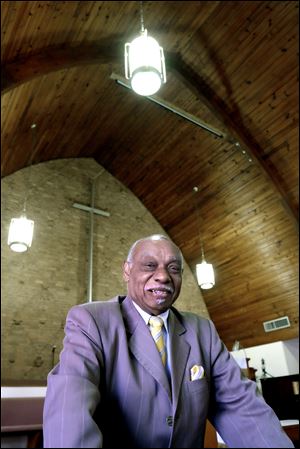

The Rev. Floyd Rose is shown in the sanctuary of Serenity Christian Church. A member of the previous congregation said the ceiling was like the hull of a ship used by slavers.

THE BLADE/JETTA FRASER

Buy This Image

The second in a series

The Rev. Floyd Rose is shown in the sanctuary of Serenity Christian Church. A member of the previous congregation said the ceiling was like the hull of a ship used by slavers.

VALDOSTA, Ga. — The Rev. Floyd Rose preaches from the pulpit of a southern Georgia church whose sloped wood-paneled ceiling resembles the upside-down hull of a slave ship.

Beneath that beautiful but cruel reminder, his 50-member congregation sang “The Black National Anthem” to begin a recent service.

Serenity Christian Church, which Mr. Rose founded seven years ago in his hometown of Valdosta, Ga., doesn’t rival the size of Family Baptist Church, the Toledo church he grew from a handful of parishioners to packed pews of 400.

But in Valdosta, his phone still rings with requests for help, and the reputation he earned during his nearly 40 years in Toledo as a firebrand pastor and civil rights leader continues to bring accolades and condemnation.

He rose to prominence in 1980s Toledo.

He rallied marchers, organized boycotts, fought for minority hiring and contracts, and served a two-year term as the local NAACP chapter president.

He retired in February, 1995, after 25 years as the ombudsman for Toledo Public Schools.

He returned to the South, just miles from where he was born, the second of 12 children, and where his father toiled as a sharecropper.

He reassured his family that activism, like Ohio, was in the past.

“This ain’t Toledo. These people will kill you,” he remembered his wife crying.

Then the calls kept coming. He couldn’t say no.

“A man has to do what a man is,” he said.

VIDEO: The Rev. Floyd Rose speaks at the Serenity Christian Church

IN PICTURES: Rev. Floyd Rose

The Floyd Rose now in Valdosta is 78 years old and surrounded by the Deep South’s troubled history. Age and address haven’t changed him. He is still a fighter.

He started Serenity, his second church since moving back to Georgia, after a week of fasting and prayer. He bought the building before he had members.

A couple of years later, two coincidences inspired him to open a history museum. The church street number, 1619, matches the year the first ship brought slaves to Jamestown, Va. The church telephone number ends in 1863, the year President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

ABOUT THE SERIES

African-Americans are returning to the South in record numbers, reshaping a region millions of blacks abandoned during the Great Migration. Reporter Vanessa McCray and photographer Jetta Fraser spent a week driving through Georgia and Mississippi and visiting former Toledoans.

During Black History Month, The Blade tells their stories.

Sunday: Gail Rayford-Ambeau

Coming Tuesday: Anne Brodie

Wednesday: George Armstrong

Thursday: Birdel Jackson

Sunday, Feb. 12: Young, educated blacks are leading the exit south. What can Toledo do to retain these bright minds?

Portraits of important African-Americans now fill Serenity’s classrooms and hallways. The displays showcase black inventions and timelines stretch from Africa to former President Barack Obama.

The Rev. Rose also leads the Valdosta chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Recently, he’s been haranguing school board members about the paucity of contracts awarded to black businesses for an $85 million school construction project.

This is what retirement looks like.

“I just love it here. I’m happier than I’ve ever been in life,” The Rev. Rose said. “I believe that God has reserved in me, as in everybody, a space only for himself. If you try to fill it with anything else, you’re going to be miserable, and you may never know why.”

Valdosta work

His advocacy in Valdosta has won him unexpected allies, including the city’s white police chief.

The Sunday before Martin Luther King, Jr., Day, Brian Childress presented the Rev. Rose with an honorary police chaplain badge.

The chief placed it around the pastor’s neck. The gold shield remained tucked next to the Rev. Rose’s striped yellow tie for the rest of the church service.

“Reverend, you’ve been fighting a long fight for a long time,” Chief Childress said. “You’ve been working hard to — let’s be honest about it — make sure law enforcement treats everybody the same.”

The Rev. Floyd Rose receives a Valdosta Police Department chaplain's badge from Valdosta Chief of Police Brian Childress. Mr. Rose is the founder and senior servant at Serenity Christian, ‘The perfect church for imperfect people.’

Since becoming chief almost four years ago, Chief Childress has tried to restore trust between the police and the 54,518-population community that is 51 percent African-American.

In the 1990s, a previous chief was convicted of stealing government property, and Chief Childress said the police department hasn’t historically reached out to black leaders.

The chief has shown the pastor videos of officer-involved shootings. Mr. Rose credits the cooperation for the lack of complaints he has received since the chief took office.

Their duties sometimes put them on different sides of a dispute.

In 2005, the Rev. Rose wanted Valdosta to rename a park that bore the name of a white segregationist. He led 14 other protesters to council chambers, where they refused to budge and were arrested. Mr. Rose’s charges were eventually dismissed, and the park is now called John W. Saunders Memorial Park after the county’s first black agricultural extension agent.

Chief Childress, then a captain, told the local newspaper that the police department had warned the group ahead of time that they would be placed into custody if they disrupted the meeting or broke the law.

As chief, he said his goal is to avoid arrests, but he understands Mr. Rose “has to continue his civil rights work.”

“He’s the MLK down here,” said Chief Childress, as he left the church and headed into the warm January sunshine.

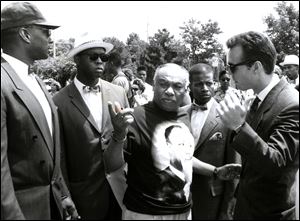

The Rev. Floyd Rose, accompanied by members of the Nation of Islam, speaks with Kevin Lent, right, of Franklin Park Mall, about the lack of black mall employees in June, 1992.

History in Toledo

Standing up for his convictions led to plenty of confrontations when Mr. Rose lived in Toledo.

One of the earliest came in 1981, when he faulted Toledo Mayor Doug DeGood for not interviewing black city manager candidates.

The next year, Mr. Rose filed a federal discrimination lawsuit against Lion Store. The publicity-savvy leader with a flair for the dramatic recalled taking a couple of buses to the store and asking protesters to cut up their credit cards.

“After that, they ended up hiring some black folks,” he said.

He put the heat on Macy’s, getting the department store in 1985 to remove women’s blazers made in South Africa.

His apartheid protest continued in 1986 during a national Coca-Cola boycott. Mr. Rose pressured dozens of local stores into removing Coke products from their shelves. He traveled to Coke’s headquarters and held news conferences until he received assurances that the soft-drink giant would exit South Africa.

In 1988, in a city hall scene reminiscent of his Valdosta protest, Mr. Rose and his supporters were arrested after they refused to vacate Toledo councilmen’s chairs. The group objected to the suspensions of three black city employees.

During those and other battles — notably ones in which he questioned police — Mr. Rose drew ire from both black and white critics.

“He was telling them what was right,” said Bishop M.C. McGhee, who marched alongside Mr. Rose and now pastors a Toledo church that shares the name Serenity. “When you stand up for the right, there’s always going to be consequences.”

Controversy followed him to Georgia.

“Many people just can hardly stand him, and other people love him. It depends on which side of the question you are on. He gets a lot of phone calls from people looking for help because they know he will stand up and speak out,” said Bob Elder, a retired businessman who lives in Valdosta.

He and the reverend have met weekly for years to swap white and black perspectives on various topics.

“I love him as a brother,” Mr. Elder said. “If everyone in this country would be like him there wouldn’t be a problem.”

Southern roots

Valdosta has family ties to thank or blame for Mr. Rose’s decision to move there.

His gravelly voice quivered when he talked about his father’s hard life as a rural Valdosta sharecropper, born in 1915.

“He worked all year and when he finished … the man says, ‘You almost made enough money to get out of debt. You almost got out of debt,’ ” Mr. Rose said.

Fed up after two years, Alonzo Rose moved the family into town and started preaching. They lived in the parsonage and bathed in the baptistery.

Four of the five boys grew up to be preachers like their dad.

The family moved to Atlanta when Mr. Rose was about 5. He earned a reputation as a troublemaker, slapped a teacher, and was sent to a Christian boarding school in Tennessee.

His preaching talents earned him a spot on the revival circuit. The youth toured the country and caught the attention of Billie Sol Estes. The rich, white Texan asked to pay for Mr. Rose’s education.

Later convicted of fraud, Estes became synonymous with swindling scams. Mr. Rose remained loyal to his benefactor. When he died in 2013, Mr. Rose said Estes’ family asked him to deliver the eulogy.

Mr. Rose came to Toledo to lead a church in 1959 at the suggestion of his father, by then a minister in Detroit.

His dad always considered Valdosta home.

Once, while preaching at his son’s church, illness overcame the elder Mr. Rose. His son tried to pry his father’s hands off the podium, but the older preacher was adamant. He would not go to a Toledo hospital. He wanted to take his last breath back in Georgia.

His father recovered and, in 1964, fulfilled his wish to return home. He died in Valdosta nearly 30 years later.

“I never thought I’d move back down here,”Mr. Rose said. “I came down for his funeral, and I don’t know — after that I just kind of wanted to come home. I never did understand why he always wanted to come back.”

Ancestry, not geography, beckoned Mr. Rose.

“If you’re the son of a former slave, you can’t feel like you’re the son … of a slave owner,” he said. “That’s just different.”

Differences

Now that he’s spent decades in the North and South, Mr. Rose can compare the two.

There’s prosaic observations: “If you notice, the streets and everything are nice down here, unlike Toledo.”

John W. Saunders Memorial Park in Valdosta, Ga., had previously been named for a white segregationist. The Rev. Floyd Rose and his followers convinced officials to change it.

And cultural perceptions: “Down here, if one white man loves you, and he’s got some money and prestige and he speaks for you, or speaks on your behalf, you can just get about anything you want.”

In Toledo, he said, he “never did figure that out.”

His son, Gerald Rose, was born in Toledo and moved to the Atlanta area.

He admitted to worrying about his outspoken father’s physical safety.

“I pray for my dad every day because he’s even more Deep South than me,” said the 50-year-old.

The younger Mr. Rose said he learned from his father to not let fear keep him from pushing for justice.

The reverend’s parishioners feel fortunate he left Toledo for Valdosta.

Delores Dennison tried to explain how much he means to the community, church, and to her.

“He’s just a people’s person, and he can relate to anybody,” she said.

Like Valdosta’s police chief, Twanna Monlyn described her pastor as “today’s Martin Luther King.” She’s lived in Valdosta for 15 years and attended Serenity for about five.

He made a big impression one day when she came to clean the church. The reverend was on his way to help get a woman out of jail.

“She was guilty, but still he was going down there to speak on her behalf, to ask the judge to please give her another chance,” Ms. Monlyn said. “He told me that one morning about 8 o’clock, and I didn’t stop crying until 12 o’clock. It touched my heart.”

She called him a civil rights leader, father figure, mentor, and counselor.

“He’s just whoever, whenever, whatever. He’s there for you,” she said.

As for the wherever: It’s now Valdosta.

Contact Vanessa McCray at: vmccray@theblade.com or 419-724-6065, or on Twitter @vanmccray.