Toledo family shattered by cycle of violence

Slain 16-year-old’s father was same age when he killed a Toledo teen

9/4/2017

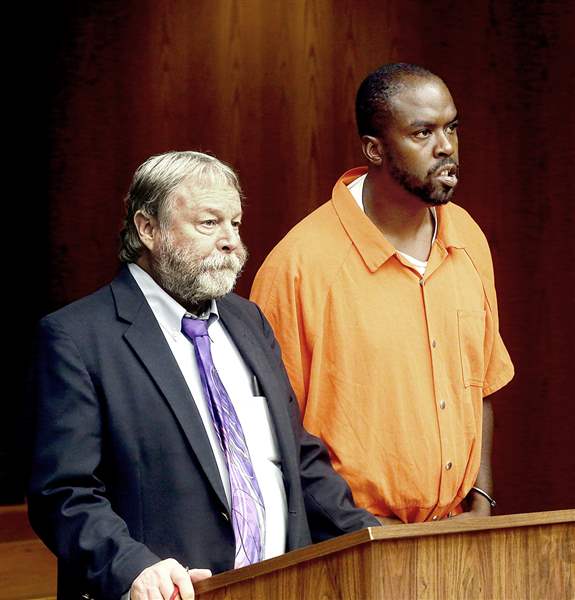

Shellton Hicks, right, whose son was killed in June, stands last month with public defender James MacHarg in Toledo Municipal Court on new charges. The elder Hicks previously shot and killed another teenager.

THE BLADE

Buy This Image

On the blisteringly hot afternoon of June 11, Shellton Hicks was sitting on a bright blue bench in the Sherman Elementary School playground when three men on bicycles approached him.

Not so many years before, Shellton had played with friends on the jungle gym outside the school, which was only a few blocks from his childhood home. But on this summer day, he seemed agitated, arguing with the bicyclists, then turning his back and walking out of the playground. A grainy security-camera video shows one of the bicyclists following him, through a narrow metal gate and onto the sidewalk.

Moments later, near the corner of Walnut and Peck streets, Shellton was shot once in the back of the head. He died later that afternoon at Mercy Health St. Vincent Medical Center, with his mother by his side. He was 16.

Shellton Hicks, right, whose son was killed in June, stands last month with public defender James MacHarg in Toledo Municipal Court on new charges. The elder Hicks previously shot and killed another teenager.

RELATED CONTENT: Indictment handed up in death of Toledo teen ■ Motive for slaying teen not known yet

“He did not deserve to get shot in the head like that,” Shellton’s mother, Fredlisha Hughes, said in a recent interview. “The video is what makes me sick. I know they didn’t care. Broad daylight? They don’t have no heart.”

The playground shooting was Toledo’s 20th homicide of 2017, putting the city on track for one of the bloodiest years in its recent history. But the tragic episode was significant for another reason, as well — it was not the first local shooting involving a young man named Shellton Hicks.

Sixteen years ago, during a May, 2001, gang clash in central Toledo, Shellton’s father, also named Shellton Hicks, shot and killed a 16-year-old boy. Ultimately, he pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to eight years in prison.

When his father pulled the trigger that day in 2001, the younger Shellton Hicks was just 10 months old. The older Shellton Hicks was 16 — the same age as the son he lost in June. Even as urban crime rates fall nationwide, the story of the two shootings — father and son, one a teenage killer, the other a teenage victim — illustrates the cycle of violence that ensnares so many young men in Toledo.

“You cannot separate this sort of gun violence in African-American communities from poverty, unemployment, drug use, drug sales, mass incarceration, and overpolicing,” said Hasan Jeffries, a history professor at Ohio State University. “If I don’t recognize your humanity, it’s in part because my humanity is being denied by the larger society.”

On July 3, shortly after releasing the security footage from the playground, police charged Darnell Bryant-Bey — an 18-year-old known on the streets as “Smiley Sosa” — with murder. A former high school classmate of Shellton’s, Mr. Bryant-Bey pleaded not guilty and is scheduled to stand trial on Sept. 11. If convicted, he could face life in prison.

‘One that hit the guy’

Before he fired his semiautomatic pistol in a moment of panic, the elder Hicks had never heard of Jerome Morgan, the high school basketball star he killed on the night of May 12, 2001.

It was nearly 11 p.m., and Hicks and a group of youths, some of them affiliated with the Crips street gang, were walking home through an alley near the intersection of Ambia Street and Lawrence Avenue.

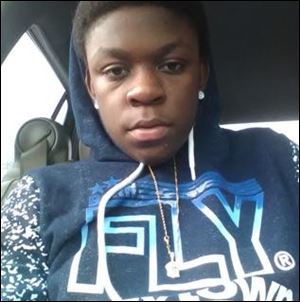

Shellton Hicks, who was shot and killed in June in North Toledo.

A second group that included Jerome and several men associated with the Crips’ rival gang, the Bloods, was walking along Lawrence on the way back from a party, screaming insults at the Crips and firing bullets into the air.

“Shots were being fired in my direction, and I shot back,” Hicks said at a hearing more than six months later. “I believe one of the bullets was the one that hit the guy.”

Although members of the Bloods and Crips were at the scene of the shooting, neither the elder Hicks nor Jerome actually belonged to a gang, police said at the time. Jerome played basketball for Central Catholic High School and planned to attend college. Hicks had only a few minor blemishes on his record. In court, his lawyer described him as “a kind young man” and “not a troublemaker.”

Hicks was charged with murder, but in a plea bargain was sentenced to five years in prison for voluntary manslaughter, plus an additional three years for using a gun. Reached by phone, he refused to discuss his son’s death, the 2001 shooting, or his life since.

But court records show he has struggled to get back on track since his release in 2009. In the past eight years, he has been arrested more than a dozen times for a range of offenses, from trespassing to drug dealing. In 2012, he underwent court-ordered psychiatric treatment before serving three years for owning a gun, which is illegal for a convicted felon. In April, police say he was caught with a gun and six packages of cocaine. He was arrested, had a pretrial hearing in August, and is now in custody at the Lucas County Jail.

While Hicks served his prison sentence in the early 2000s, Ms. Hughes — 21 years old at the time of the shooting — raised their son on her own, with help from her family.

“I loved him, and he got himself into that, but taking care of my kid wasn’t a problem,” she said. “It was just a part of us wasn’t there, because he was gone.”

Even as a young man, the elder Hicks seemed aware that his absence would have consequences for the people he was leaving behind. At his sentencing, after expressing remorse for the shooting, he delivered a more personal message: “I would like to apologize to my family for not being there right now.”

Still, Hicks managed to develop “a little bond” with his son, Ms. Hughes said. In the early 2000s, when Shellton was a toddler, she took him to visit his father in prison, and after Hicks was released, he and Shellton spent time together.

Hicks encouraged his son to play basketball and “tried to keep him focused,” said Shellton’s teenage girlfriend, Alexes, who asked that her last name and exact age be withheld for safety reasons.

“His dad helped him when he needed it,” Alexes said. “He never talked bad about his dad.”

‘Rambo’

Across the street from the hospital where Shellton died, and not far from the playground where he was shot, stands the federally subsidized apartment complex Moody Manor.

In 2013, Moody Manor became synonymous with violent crime, when two local men were sent to prison for killing one toddler and seriously injuring another in a shooting inside the complex. The shooters belonged to the Manor Boyz, a Toledo street gang based at Moody Manor and affiliated with the Bloods.

Until last year, Shellton lived in Moody Manor with his mother and two younger half-brothers. It was there he got his nickname, “Rambo,” an apparent homage to the gangster rapper Brice “Rambo” Rhodes. Friends describe Shellton as a fun-loving jokester who liked to shoot hoops and play videogames. But he also had another side.

“He wasn’t an angel,” Ms. Hughes said. “He made silly decisions as a teenager.”

Before the shooting, city police considered Shellton and Mr. Bryant-Bey to be “gang associates,” according to police gang unit director Ed Bombrys. On Facebook, the teenagers posted about the Manor Boyz, suggesting that they may both have belonged to the gang, which has about 50 members. In several photographs, Shellton, whose online moniker was “Rambo Mb,” can be seen pointing a gun at the camera.

Gang membership often appeals to young men who have few alternatives to a life on the streets, said Ray Wood, president of the local branch of the NAACP. In Toledo, nearly 44 percent of African-Americans live in poverty, according to Census Bureau data. Last year, Toledo Public Schools had the second lowest graduation rate in Ohio.

“If they had options, they wouldn’t be in those situations,” Mr. Wood said. “Nobody grows up thinking, ‘I can’t wait to get old enough to be shot by somebody.’ ”

Police spokesman Kevan Toney and Frank Spryszak, an assistant Lucas County prosecutor, declined to comment on the motive for the shooting. But Mr. Bryant-Bey’s older sister, Lakesha Brown, said her brother and Shellton had butted heads over a “trivial, child problem.”

Shellton overlapped with Mr. Bryant-Bey at Woodward High School, before transferring last spring to Phoenix Academy, a charter school designed to accommodate students who struggle academically. In the classroom, Mr. Bryant-Bey was a “crazy student” who cracked loud jokes, said Lavaughn Marshall, a friend of Shellton’s from Woodward.

But Lavaughn said he was shocked to hear police had charged Mr. Bryant-Bey with Shellton’s murder.

“I was like, ‘Dang, what happened?’ ” he said.

Cycle of violence

Toledo’s homicide rate hovered in the low 20s during the first decade of the 2000s. But over the past seven years, it has risen to an average of nearly 30 killings a year. In the two months since Shellton was shot in June, nine more people have been killed in Toledo. A total of 29 people have died this year, outpacing the 19 homicides recorded by this time in 2016. The city is on track to exceed last year’s total of 36 homicides, which was the city’s highest death toll since 2012.

Gun violence in Toledo and other U.S. cities dates back at least to the 1980s, when aggressive policing during the War on Drugs led to mass incarceration, creating a cycle of violence and poverty in the black community that continues to this day, Mr. Jeffries said.

“This isn’t just a function of there’s no dad in the home, and everyone needs a dad,” Mr. Jeffries said. “It’s about the breakdown of a community, and pulling valuable human resources out of the community. It’s not just a dad who disappears in many communities. It’s a dad and and an uncle and a person who would’ve filled in for both of them.”

During the final year of his life, a decade and a half after his father went to prison, Shellton understood that Toledo could be a dangerous place.

“He didn’t trust people,” his mother said. “Everybody from the same neighborhood started turning on each other.”

Last March, one of his friends, a 19-year-old named Trevon Bradley, was shot to death in East Toledo. News of his death left Shellton “broken,” said his girlfriend, Alexes.

“I told him, ‘Shellton, this is not what you want,’ ” she said. “I tried to keep him off the streets. Try to get him a job, to make him graduate. He was going down the right path. We didn’t really talk about no bad stuff. I always said: ‘Tell me something good. What did you do good today?’ ”

Shellton hoped to get a job by the end of the summer, possibly at a local restaurant. In the fall, he was set to begin 11th grade at Phoenix — a fresh start at a new school. And yet, throughout the spring and summer, even with his prospects apparently brightening, Shellton seemed afraid.

“He was scared to be shot in the head,” Alexes said. “That was his worst fear — to be shot in the head.”