Funeral homes serve as beacons for Toledo's black community

3/3/2018

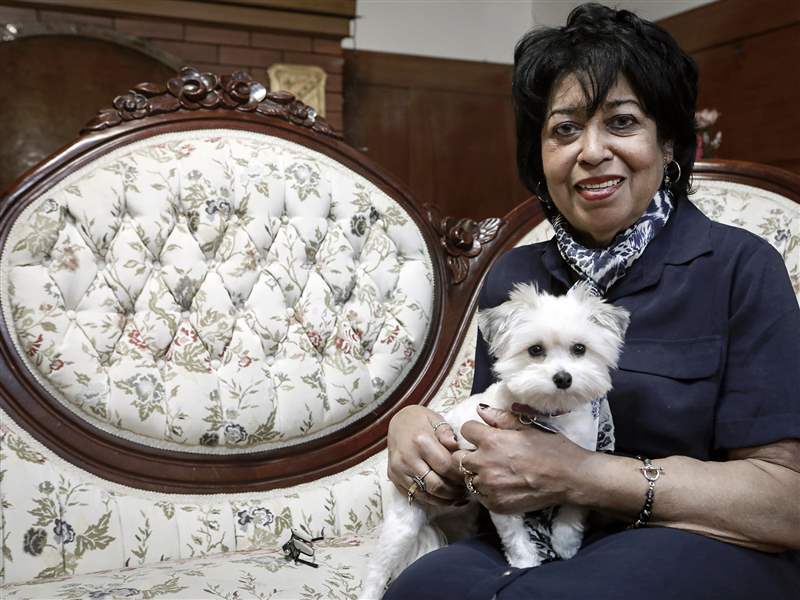

Sheryl Riggs and her maltipoo "Brie" at Dale-Riggs Funeral Home.

The Blade/Andy Morrison

Buy This Image

Generations return to the funeral homes serving Toledo’s African-American community for the measure of solace their forebears found, solace built on the distinct place funeral homes have occupied in the black community.

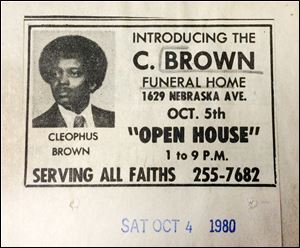

“The black funeral home was like a beacon in the night,” said C. Brown, who was born in Arkansas, grew up in Toledo, and opened C. Brown Funeral Home in 1980.

Sheryl Riggs at Dale-Riggs Funeral Home.

In decades past, new arrivals from the South realized they could ring the bell of a funeral home — even at 3 a.m. — and get a cup of coffee and a couple dollars to stay at a rooming house. Some homes have opened their doors to wedding ceremonies. Others offered a hiding place to civil rights activists seeking refuge from those intent on doing them harm.

“We cherish those who assist us in times of bereavement,” said Richard Brown, 44, founding pastor of Rock Church on Airport Highway. “We want to go someplace we have a relationship with. Funeral homes in our community have been that for us.”

Three Toledo funeral homes, in a line down Nebraska Avenue within 2 ½ miles, are operated by African-American directors and embrace that role. C. Brown Funeral home is the newest. In 1964, Dorothy and James Day opened what is now the House of Day Funeral Service. The oldest, Dale-Riggs Funeral Home, traces its lineage to Toledo’s first black-owned mortuary, opened by Elvin Wanzo in 1912.

VIDEO: Sheryl Riggs discusses the history of Dale-Riggs Funeral Home

“You have to look at funeral homes as institutions in the African American community,” said Robert Smith, 70, of the African American Legacy Project of Northwest Ohio. “You could be guaranteed certain families, entire families, would use a particular funeral service.”

But these institutions also are businesses exposed to societal and economic forces — would-be clients moving away from traditional neighborhoods, their children scattered several states away; changing demands for services; loyalty tested by funeral home chains with broadcast ads touting low-cost funerals.

“Funeral service in the African American community changed just like anything else when segregation ended,” said Carol Williams executive director of the National Funeral Directors & Morticians Association, a membership organization for African American funeral directors.

The Dale-Riggs Funeral Home on Nebraska Avenue traces its lineage to Toledo’s first black-owned mortuary, opened by Elvin Wanzo in 1912. Clarence ‘Jack’ Dale took over the business in 1946.

Across the country funeral homes that traditionally served African-Americans find themselves not competitive and eventually close, Ms. Williams said.

Toledo funeral homes raise triple shields of service, familiarity, and reputation against changes in attitude and market pressures.

Aaron Day, 35, social media specialist at House of Day — and a grandson of the founders — said the firm emphasizes to the community that it is family owned and local.

“They see us in the community and know us. They grew up with us, a lot of them,” Mr. Day said. “We change as the years go, but we stick with the traditional way of doing things.”

‘Warm and friendly and kindness’

Those who came before offered a template. Sheryl Riggs had 15 years’ experience in the funeral business in her native Detroit when she started anew in Toledo.

“I thought I was the best thing going,” Ms. Riggs, 71, said. Then she arrived to work with Clarence “Jack” Dale, who in 1946 took over Wanzo Funeral Home in a grand old house with a turret at Nebraska and City Park Avenue. Years later, Mr. Dale and his wife, E. Genevieve Dale, co-owners of the mortuary, needed someone to take over.

“He found a company that could afford to buy it,” Ms. Riggs said. That turned out to be Wilson Financial Group of Houston, which had begun acquiring black-owned funeral homes. Mr. Dale officially retired — and continued working with Ms. Riggs, who with the sale in 1992 was named managing director of what became Dale-Riggs Funeral Home.

Ms. Riggs knew how to run a funeral business. From Mr. Dale, “I learned how to really relate. It wasn’t anything solemn. It was warm and friendly and kindness.”

C. Brown, 70, knew he wanted to go into funeral service and, ultimately, own a funeral home, after working for Mr. Dale and another funeral director, Van T. Sherrill and, as a junior high student, pitching in at the funeral home owned by Clifford Brown — no relation — on Grand Avenue.

“I learned a lot from him, how to do things, and a lot from him how not to do things,” Mr. Brown said.

That evolved into “how to do those things, but do them better, if you’re going to work with the public. He was a gentleman. He knew how to handle the public,” Mr. Brown said.

C. Brown says he spends little on advertising, aiming instead to treat his clients as individuals.

Mr. Dale, who died in 2002, also was a leader in Toledo-area business, civic, and charitable groups.

Through the years, funeral directors often shared their religion or nationality with those being served or had some other connection, said Joe Coyle, of Coyle Funeral Home, family owned and operated since 1888.

“It’s such a difficult emotional time,” Mr. Coyle said. “The ties that bind somebody to you make you feel comfortable calling.”

Homegoing

The particulars of black history in America, with life so tenuous at times, served to strengthen those ties, some scholars argue.

Suzanne E. Smith, author of To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death, said the concept of “homegoing,” a term used for a traditional church funeral service to celebrate the deceased’s return to Jesus, dates to the Middle Passage and the belief that the spirits of those who died would indeed return to the home from which they enslaved.

Embalming as a consistent practice for preserving bodies only followed the Civil War. Mortuary businesses opened, but families typically held wakes at home. Funeral homes as physical buildings didn’t become a widespread phenomenon until the 1920s, said Ms. Smith, a professor of history at George Mason University.

Cecelia Adams, 67, accompanied her late maternal grandmother, a Pentecostal minister, to wakes and services.

“The funeral home was a place of care and comfort where you could go and celebrate the life of a person or a loved one who had been lost,” said Ms. Adams, a Toledo City Council member and retired educator.

And there was a style to be found, Ms. Adams said. After removing the flowers and closing a casket, Mr. Dale pulled a handkerchief from his suit coat and carefully wiped off the casket. He then folded the handkerchief and returned it to his suit pocket.

“It was one of those moments you waited for,” Ms. Adams said. “It was so classy. Even in a sad situation, it was so cool.”

Black funeral directors serving the black community was a “specifically twentieth-century narrative of color and class, mortuarial and ministerial alliances, and ceremony and performance,” wrote Karla FC Holloway, a professor emerita of English at Duke University, in her 2002 book, Passed On: African American Mourning Stories. “All indications are that the twenty-first century will form a different narrative.”

Color lines solidified for most of a century as black businesses prepared the community’s dead for burial, she wrote later in the book. And those lines were being transgressed, not by “the force of necessity, nor was it a reaction to threats of hostility or intimidation. It was a matter of choice,” she wrote.

That included the choice to use funeral homes outside the African-American community.

Tradition loosens

The shift has been reciprocal, Ms. Riggs said, at least in Toledo, Detroit, and Cleveland: “Everyone is willing to serve everyone. A white funeral home will be eager, because everyone’s learned that money is green and so the client is made to feel welcome.

“There were places you couldn’t go. You weren’t wanted years ago,” Ms. Riggs said. “Some providers in Toledo would call [Mr. Dale] and say, ‘Jack, I’ve got a black body here. I’ll send it over.’ They didn’t want to deal with it. Society is just more open.”

Families without life insurance and young adults who hadn’t prepared for a death “will look for the most economic package,” Pastor Brown said, “and if the most economic package is offered by a white-owned funeral home, they’ll take it. The older generation wouldn’t think about using a funeral home outside the community.”

Cremation, once written off by some for religious reasons, gains year by year. A July, 2017, report by the National Funeral Directors Association found that cremation was used in 50.2 percent of 2016 U.S. deaths, up from 48.5 percent in 2015. And most of those had a funeral-home involved service — whether a traditional viewing or a memorial service.

Mr. Brown, the funeral director, and the others lay out the options — what is available at what cost — when families make arrangements. He spends little on advertising, especially not to counter television ads of chains promising lower prices than local firms.

“Enough people have enough sense to know better,” Mr. Brown said. Instead, he aims to treat clients as individuals.

“You have a pipeline to where people know you’re a straight shooter, and in talking to them, they’ll listen, some people,” Mr. Brown said. “Some don’t know, and they feel they’ve been educated in listening to you. You gain some type of a following because they find out it’s the truth.”

As the pull of tradition loosens, Ms. Riggs has a ready answer for the family that asks for cremation with a memorial service months later when everyone can be there, or a funeral that is quick and simple, or even green friendly.

“Sure, I can do it,” Ms. Riggs said. “I’m interested in giving you all your choices, and then you tell me what you’d like to do.”

Contact Mark Zaborney at mzaborney@theblade.com or 419-724-6182.