School funding disparity remains 20 years after landmark DeRolph decision

8/15/2018

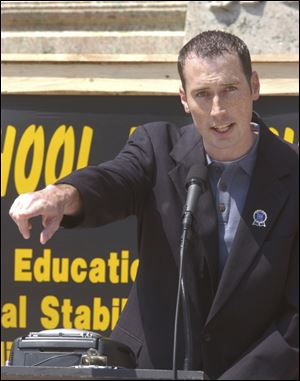

Nathan DeRolph, who in 1991 started the original lawsuit that led to an Ohio Supreme Court ruling that the state's school funding system was unconstitutional, gestures during a school funding rally at the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus.

COLUMBUS — Two decades since the Ohio Supreme Court first struck down the state’s method of funding education, the state’s poorest districts receive just 3.8 percentage points more in operating funds than their wealthiest counterparts, a study released Wednesday revealed.

That translates into an inflation-adjusted difference of just $107 more per pupil.

In 1997, the state Supreme Court issued its first 4-3 decision — now known as the first DeRolph decision — in a landmark case brought on behalf of a public school student in Perry County. It found that the state’s method of funding education at the time fell short of meeting the constitutional mandate of providing a “thorough and efficient” system of education for 600-plus districts.

It found the system placed students in property-poor districts at a competitive disadvantage compared to their counterparts in wealthier districts. The court later reaffirmed that decision twice and then surrendered jurisdiction in 2003.

In the first 10 years after that decision, some improvement was made in leveling the playing field between the state’s poorest and wealthiest districts, said Howard Fleeter, whose Columbus research firm conducted the study for the Ohio School Boards Association, Buckeye Association of School Administrators, and Ohio Association of School Business Officials. But since then, the improvement has been stagnant.

“In fact, overall, state funding for education from 2009 to 2019 hasn’t even kept pace with inflation,” he said.

VIDEO: The Blade’s Jeff Schmucker on school funding study

In the immediate wake of the DeRolph decision, the state did increase funding for K-12 schools and tried to steer more of those increases toward poorer districts through a frequently changing formula. It also poured billions into building new schools across the state, a move that Mr. Fleeter said showed the “literally concrete difference that ruling made.”

But the study focuses on operational aid from the state funding formula, local property and income taxes, and casino revenue.

“You can’t just build buildings and say, OK, everything’s fine,” Mr. Fleeter said. “You need to make sure that these districts have the money to staff these buildings [and] offer the same programs in low-wealth places that the high-wealth places have. That’s why we’re focusing on the operating money.”

The study does not offer specific funding recommendations.

“For those that only quantify educational success by how much is being spent, they should be happy state education funding is at an all-time high — up over $1.5 billion since the governor came into office,” said Jon Keeling, spokesman for Gov. John Kasich.

“But we prefer to focus on the real policy reforms led by this administration that have been designed to improve student success over the past eight years,” he said.

After early funding increases, the 2008 recession hit. Then the state slashed income taxes and completed the phase-out of an unpopular business tax from which schools benefited.

Ryan Stechschulte, treasurer for Toledo Public Schools, said the current funding formula isn't fair, as property values and a community’s ability to pay for schools varies heavily across the state.

He hasn't seen a state funding system that totally fixes the problem, but said the reliance on property taxes in Ohio forces districts to repeatedly come back to voters to ask for funds.

"It's very difficult to convince the voters to fund school properly, as it's a complex formula and variables can change that the school district has no control over, which will then force us to try to generate the revenue in another fashion," he said.

While TPS may receive more per pupil from the state than others, that's due to poverty levels, he said.

"There's enough studies out there that would show that students who are in poverty or who grew up in poverty need additional services to become successful," he said, "and that suburban schools don't necessary need to provide all those compared to Toledo."

Although Ottawa Hills is among the state’s wealthier districts, Ohio's reliance on property taxes to fund schools causes difficulties, Superintendent Kevin Miller said.

State funding has gone up for the district since DeRolph, but not enough to keep up with inflation, he said. And as a wealthier district, Ottawa Hills has to rely more on local property taxes than others.

Mr. Miller said his community is one of the highest taxed areas in the state, and while residents have been willing to continue providing operating funds for the district, it makes finding funds for capital improvements difficult.

"It's kind of a Catch-22 for us a little bit," he said. "Our folks do everything they can on the operating side, that when you get to the capital improvement side, they are kind of tapped out."

State funds for building improvements are tied to local property values, which puts Ottawa Hills both at the back of the line and also means state funding levels would be proportionally low compared to other districts.

What to do about that is difficult, he said. In general, he believes the state should have a flat rate that funds the "minimum educational experience," and, if a district wants to ask residents to pay for a level higher than that, it can.

"It's depressing to me that truly so many years after the DeRolph case was decided we really have seen minimal change," he said.

Tom Hosler, Perrysburg's superintendent, is part of a school funding workgroup put together by Reps Bob Cupp (R., Lima) and John Patterson (D., Jefferson), that is examining structural changes to Ohio’s education funding. A report is expected later this year.

Right now, he said, Ohio's model is complicated and ever-shifting, leaving residents confused and school officials uncertain about what their budgets will look like a few years down the line. Because of Ohio's tradition of local control, districts constantly go to voters to approve or renew levies. He said thousands have been put on the ballot since DeRolph.

"That is really, really challenging," he said. "We have to overly rely on local property taxes, and that hurts."

Perrysburg has been a fast-growing district, but state funds haven't kept up with that growth, putting a strain on the district's budget despite enrollment increases. And while legislators have increased overall funding for schools, most people don't realize that there's been funding leaks out of the districts from charter schools and vouchers, among others issues.

"What oftentimes is lost in the budget is that there are more holes being poked at the bottom of the bucket," he said.

Mr. Hosler said he's looking for a system that doesn't create winners and losers, but how the state balances local control traditions with equitable funding is a conundrum that's hard to fix.

"I think the thing that is really troubling in terms of the equity piece is the recognition that students who live in poverty, students who have additional needs for extra support, are going to require additional funding," he said.

Wednesday’s study found that the average property tax millage rate for operational purposes for the 120 poorest districts was just 1 mill less than the average levied by the wealthiest 120. A mill in a wealthy district generates much more revenue than a mill in a poor district.

From fiscal year 2009 through the current fiscal year 2019, the lowest wealth districts received 29.4 percent in state and local revenues after adjusting for inflation compared to 25.6 percent for the high-wealth districts.

Since fiscal year 1998, total state and local resources for schools have climbed from nearly $9.7 billion to an estimated $18.8 billion for the current fiscal year. The state’s share of that funding has climbed during that period from 38.5 percent to 43.3 percent.

While state and local K-12 funding climbed a total of 83.4 percent during these two decades, the net increase after adjusting for inflation was 21.7 percent — an annual average of 1.1 percent.

Contact Jim Provance at jprovance@theblade.com or 614-221-0496.