Homeowners, renters strain to get guidance

12/18/2017

Zarlando Holloway, 60, leans on the railing in front of his Cincinnati home in August, 2017. The home, which he bought in 2015, has orders to vacate due to untreated lead hazards. Mr. Holloway said the orders were not disclosed when he bought it but is nevertheless working to rehab the entire house.

The Blade/Sarah Elms

Buy This Image

Second in a two-part series.

CINCINNATI — While lead paint proves hazardous for children and a vexing concern for public health agencies, remedying it presents other problems for some property owners, who in many cases are simply trying to make ends meet.

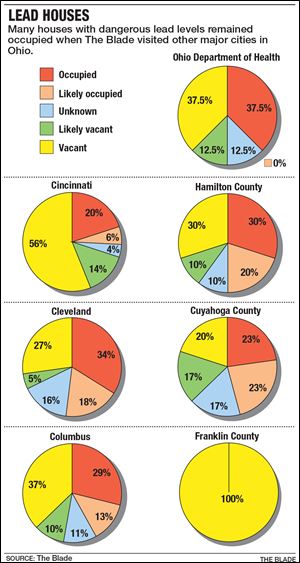

Zarlando Holloway, 60, is slowly renovating the 1925 home in northwest Cincinnati home he bought in 2015, which currently has orders to vacate due to untreated lead hazards. It is one of more than 200 homes with such designation across Franklin, Cuyahoga, and Hamilton Counties that Blade journalists visited this year after the Ohio Department of Health in May published a list of addresses with such orders.

RELATED: Renters often left in the dark about home lead levels, health risks

At each residence at least one child had been poisoned and property owners have not done required improvements. The Blade visited homes in the three counties with the most properties in the state to compare the situations with Lucas County’s.

“It’s not a cheap thing to rehab this,” Mr. Holloway said, gesturing to his house. “There is never any money.”

It’s not just the homes with orders to vacate that are desperate for repairs, he said. Many homes in low-income neighborhoods need work. Homes built before 1978 when the federal government banned lead paint for residential use are assumed to have lead in them.

“Who is going to help us?” he said. “If you gave everybody at least a $10,000 loan, that would go a long way…to get the lead paint out of the house, put new windows in the house.”

Many of the homes have been lingering on the list for months, if not years.

The lowest value houses are some of the most difficult to bring into compliance, said John Sobolewski, deputy director of environmental health at Cuyahoga County Board of Health.

“That is the difficult part, especially in places like East Cleveland because the house are so expensive to fix and there is no equity in them,” he said. “If you go to [the more affluent suburb of] Lakewood, it is much easier to get the additional dollars. There is equity in the property, so if you fix it, you know you can sell it and get some money back.”

Residents want better communication through the slow churn of government bureaucracy, said Falisa Turner, who described being in limbo with her Cleveland home, which appears on the state list.

When she and her husband found out their grandson had elevated blood lead levels, it came back to their 1910 house. Her grandson, Javen Scruggs, was living there in 2014 when his lead levels were found to be elevated, Mrs. Turner said.

Mrs. Turner, who often watches Javen, now 4, while his mother works, said they have to find other places to babysit him. Since then, it’s meant the child can’t visit their house, a major inconvenience since Mrs. Turner often provided childcare for her daughter. Now, Mrs. has to travel to her daughter’s house to watch the boy or find another location.

“They told us to clean, to paint, to do all these things. They claim they sent paperwork that we were supposed to follow up with, we have yet to receive any paperwork,” she said. “The next time I spoke to somebody was May when they put this up on the house,” gesturing to the sign. They were told they had to wait until they were approved or rejected for a grant before they could start any work on their own, she said.

“We were calling them every other week,” she said. “We haven’t called them in the last couple of weeks because we get a voicemail, we get no answer, or they tell us the same thing: ‘We’re still working on it.’”

Health department officials told them they are prioritizing houses where children are currently living, she said.

“With this up here, my grandson can’t even visit,” she said. “Without any children in the house, they aren’t going to get to me. It’s a Catch-22. For them to fix it, I have to have children in the house. But because I have this order for vacancy, I can’t have children in the house.

“They told us when they put [the sign] up, ‘Well, we’re going to say you have two weeks to move but it’s a process.’ I’ve been living here 17 years, it’s not possible, There is no place to move,” Mrs. Turner said. “I understand that probably the government was on their back about all these things they should have done so when the list came in they ran around trying to cover their own [behind].”

Cleveland health officials acknowledge that when the state’s list was published in May, they did not have a good idea of how many were occupied or had been placarded.

“There was a period of time where we did not have the capacity to follow up on those cases,” said Brian Kimball, commissioner of environment for the Cleveland Department of Public Health. Since then they have determined a little less than half are occupied, he said, and have increased the number of staffers working on these cases from two to 10.

Managing a program with a wide variety of home situations can be difficult for health officials.

“With lead [enforcement], there are various shades of gray,” said Rashmi Aparajit, program director in the childhood lead poisoning prevention program for the City of Cincinnati Health Department. “I don’t think it’s a one size fits all situation, especially dealing with a transient population.”

A diverse set of situations means a diverse set of needs and responses to health department intervention, she said. Owners they work with range from “small businesses, poorer property owners, or slumlord with millions who only wants to make money.”

“How far do you want to go, do you want to [clear the house of lead], do you want to cause a whole new problem of homeless families?” she said.

For other tenants, out-of-state landlords can lead to breakdowns in communication.

Kaytasha Phells, 23, had been renting one side of double unit on the northeast side of Columbus when the ominous placards started going up. At first, the property manager told her it was a scam and not to worry about it.

But the signs kept going up, ones that said it wasn’t safe to live there, particularly for kids under 6. And so, in early August the house was empty except the family’s mattresses as she waited for a call about a potential shelter placement.

“This is the first time I’ve ever had to deal with anything like this,” she said. “He just kept saying it was a scam.”

While her three children, who at the time were 5, 2, and 9 months, played nearby, she said she worried about what would happen to them next. Ms. Phells said in follow-up interviews she had sent her kids to stay with relatives and she spent two months sleeping in her car or paying to stay at other people’s homes before moving into a new place at the endt of September.

The owners of her former unit, Trek Chan and Connie Chin of Montreal, Quebec said they only found out about the lead issue a couple weeks earlier and were scrambling to comply with the orders. Records provided to them by the Columbus Health Department show that the risk assessment conducted after a child living there came back with high blood lead levels was done in March, 2013, the year before they became the owners.

They bought the property as part of a portfolio of several in Columbus, they said, but were unaware the house had lead hazards. They expressed frustration at being left in the dark both at the time of sale and by the property manager who did not alert them of communications with the health department.

“We're in Canada, we don't know what is going down there if a property manager doesn't tell us anything,” Ms. Chin said in a phone interview. The couple declined to provide the name of the property manager or contact information, saying they still employ him to manage their other properties.

The owners said they have applied for a lead grant from the city of Columbus, and were told it could take four to six months to fill. In the meantime, the house will be empty, they said.

Some changes have been made to the program to speed up compliance. In September, the Ohio Department of Health revised its guidelines instructing local health departments to return to properties with vacate orders every six months to ensure they are vacant and have proper signage.

And some local departments are taking on their own extra steps to make improvements.

In Cuyahoga County, Mr. Sobolewski said, officials put affidavits in the property records, detailing the identified lead hazards and orders on the house. That doesn’t necessarily prompt owners to make improvements if they continue to hold the property, but is intended to serve as a warning to future owners at a time of potential sale.

They have also tried to engage landlords before the process reaches legal action with informal office hearings to try to move toward compliance.

“The idea is that we want to resolve these cases because we do have grant opportunities...,” he said. “Whatever is left, those 32 cases, those went through a lot of process to get to the point where they were placarded. There was long periods of time working with landlords, trying to fix properties, trying to get grants.”

Blade photographer Katie Rausch and staff writer Sarah Elms contributed to this report.

Contact Lauren Lindstrom at llindstrom@theblade.com, 419-724-6154, or on Twitter @lelindstrom.