Redistricting issues coming to the forefront in Ohio, nationwide

3/5/2018

Former state representative Chris Redfern believes national Democrats missed an opportunity to challenge Ohio's congressional map.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

COLUMBUS — It’s been described as “Goofy kicking Donald Duck,” two chunks of land connected by a thin kicking foot.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court described the sprawling 7th district in the Philadelphia suburbs as "Rorschachian" — as in inkblots — when it struck down as unconstitutional a Republican-drawn congressional map and ordered lawmakers back to the drawing board.

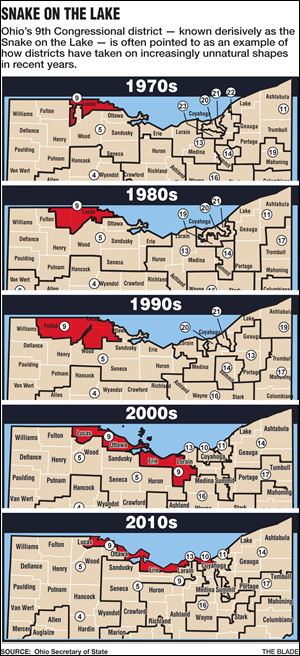

Ohio, meanwhile, has its “Snake on the Lake,” the 9th District that hugs the Lake Erie shoreline for more than 100 miles from Toledo to Cleveland, chomping at bits of Lucas, Ottawa, Erie, Lorain, and Cuyahoga counties without swallowing a single one whole.

At points, islands, marshland, and the Sandusky Bay Bridge serve as connective tissue.

U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo), represents Ohio's 9th District, also known as the "Snake on the Lake," which the National Journal called one of America's “10 Most Contorted Congressional Districts.”

Both the Ohio 9th and Pennsylvania 7th — along with districts in Maryland, Illinois, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas — were listed among National Journal’s “10 Most Contorted Congressional Districts.”

But unlike most of the other states on that list, Ohio’s map was never challenged in federal or state court or by voters. While many now point to the “Snake on the Lake” as exhibit A of what is wrong with Ohio’s current process, the map had bipartisan support when it finally passed in 2011 and the 9th will remain in place until 2022.

Justin Levitt, associate dean of research and a professor of constitutional law at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, said redistricting challenges these days are seemingly “stacked up like planes on the runway” as state courts and the U.S. Supreme Court take fresh looks at the role of partisan politics in the process.

The public is also taking interest.

“It’s still a fairly limited band of the public who connect this to issues that they care about,” Mr. Levitt said.

“I’m glad members of the press are paying attention, because redistricting is directly connected to everything. It’s how we decide who we are and how we build the country that we plan to live in together,” he added.

Under its current map, Ohio sends 12 Republicans and four Democrats to Congress, despite the fact that party registration is much tighter than that.

To this day, Chris Redfern — then a state representative from Ottawa County and chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party — believes national Democrats missed an opportunity to challenge an Ohio map he believes is every bit as unconstitutional and political as the one overturned by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

But national Democrats didn’t want to spend some $1 million to mount a voter referendum, he said.

“It’s so obscure and difficult for people to comprehend,” Mr. Redfern said. “Often times the whole process is overlooked. ... It’s a profoundly political process. Republicans passed the maps. Democrats had a chance to stop implementation.”

Republicans added an appropriation to the bill, a procedural move that blocked the referendum. However, Republicans ultimately came back to the table, making enough changes to please enough Democrats so the bill passed by referendum-proof margins in both chambers.

Matt Huffman

This cycle the National Democratic Redistricting Commission is making Ohio a priority with plans to promote bipartisan reforms of the map-drawing process that will appear on the May 8 primary election ballot as well as target elected offices — governor, secretary of state, auditor, and state lawmakers — that influence map-drawing.

“We’re the only organization that’s looking at the electoral map through a redistricting lens and lifting up the races that do have an impact on the process itself and making sure we’re doing our part to elect Democrats so that we don’t see what happened last time with the Republicans controlling the entire process and then using that power to rig the maps against Democrats,” NDRC Executive Director Kelly Ward said.

This is something Republicans figured out years ago.

“More people are seeing not only that state (district) lines did not reflect the composition of the electorate but the federal lines did not reflect the composition of the electorate,” Mr. Levitt said. “Redistricting is not the only cause of that, but it plays a substantial role.

“Republicans used it to boost Republican strength, locking in the particular gains of the tea party elections of 2010,” he said. “That was a wave election. But we expect waves to slow and ebb. They built a seawall to stop the wave from receding.”

Democrats have done the same when they’ve had the opportunity, he said.

Mr. Levitt said there’s no guarantee a legal challenge to Ohio’s map would have led to the same fate as Pennsylvania’s. The challenge would most likely be filed first before the Ohio Supreme Court, which would have looked at a state constitution that does not contain some of the same language as Pennsylvania’s.

For instance, he noted that the Ohio Constitution does not contain the “Free and Equal Election Clause” upon which the Pennsylvania Supreme Court focused its decision.

State Sen. Matt Huffman (R., Lima), instrumental in creating Ohio’s current map, has pointed to the 9th District “snake” as an example of what could not happen if voters approve the reforms on the May 8 primary ballot.

But he has never suggested the current map is unconstitutional. He said he doesn’t believe that the U.S. Supreme Court would have scuttled it if given the opportunity.

“But that doesn’t mean it’s a perfect map and that all the things that should be a part of it are there,” he said. “With the rules in this (reform plan), whether it’s a 10-year map or a four-year majority-only map, the rules would not allow this district.”

He’s also noted that the Ohio Constitution says nothing about congressional redistricting, something that would change with passage of the proposed constitutional amendment. Proposed rules that make priorities of keeping districts compact with contiguous territory, keeping counties and communities whole, and prohibiting elongated districts would make another “snake” impossible.

“A lot of these bad districts are the result of intraparty fighting with one congressman saying he wants this community or because of efforts to protect this person,” Mr. Huffman said. ”Ask Steve Austria how good he felt the map was.”

He was referring to then U.S. Rep. Austria (R., Beavercreek), who was left out in the cold when Ohio lost two congressional districts after the 2010 U.S. Census. The resulting 2011 map had Mr. Austria living in the same Dayton-area district as fellow Republican U.S. Rep. Mike Turner. Mr. Austria bowed out.

In 2015, voters overwhelmingly approved changes in how Ohio redraws state House and Senate seats, giving that authority to a yet untested Ohio Redistricting Commission that requires significant bipartisan support for passage of a map.

But Republican legislative leadership expressed little interest in applying a similar approach to congressional districts — until an outside coalition of groups like the League of Women Voters began circulating petitions for a November ballot issue taking the pencil out of their hands.

Negotiations led to the compromise that will greet voters on May 8.

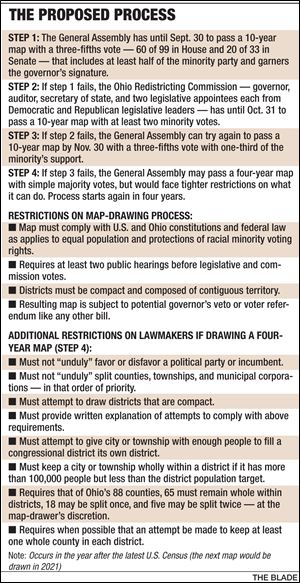

The proposed constitutional amendment would keep the General Assembly in control of at least part of the process. It would get a chance to pass a 10-year map with significant minority support before surrendering that authority to the redistricting commission that voters created in 2015 for legislative districts.

If that fails, too, the General Assembly would get one last chance to pass a bipartisan, 10-year map. As a last resort, a simple majority could pass a map that would last just four years, but that would come with additional restrictions designed to hamstring the majority lawmakers when it comes to changing lines for the benefit of a political party or incumbent.

The process could still allow bipartisan gerrymandering, cases in which the two major parties agree on a map seen as politically benefitting both. But passing a map solely along party lines would become more difficult.

“Ohio’s plan won’t fix everything,” Mr. Levitt said. “But that shouldn’t be the standard for voters to decide whether it’s a good idea. The introduction of seat belts did not immediately render cars crash-proof, but it was an important step in making them a lot safer.”

Contact Jim Provance at jprovance@theblade.com or 614-221-0496.