MLB turns to BGSU professor to help study home run phenomenon

6/18/2018

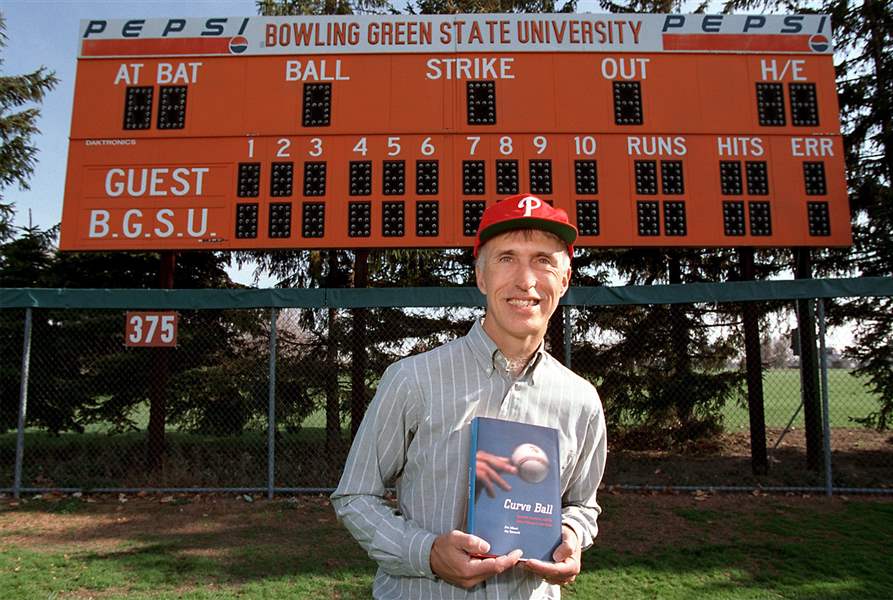

Bowling Green State University professor Jim Albert is a field leader in baseball statistics research and has written several books on the subject, including "Curve Ball."

BGSU

As Major League Baseball’s home run totals soared to unprecedented levels last season, many pitchers began to openly wonder if something had changed with the baseball.

Thanks to research done in part by a Bowling Green State University professor, MLB now knows definitively that baseballs are behaving a bit differently during their flights to the outfield.

Longtime BGSU statistics professor Jim Albert, who has done extensive research into baseball during his career, was part a 10-person committee created by MLB commissioner Rob Manfred’s office to answer one question.

What the heck is going on with all these home runs?

“When you’re a statistician, you’re basically just exploring,” Albert said. “In fact, the big task we were given was that we know there was a big raise in home-run hitting the past couple of years. We were just trying to understand more of the why. Was it a baseball thing? Was it a feature of how people are hitting the ball? Are they hitting it harder?”

During the 2017 season, MLB hitters accounted for 6,105 home runs, smashing the previous record in a season by more than 400 total homers and representing an increase of nearly 46 percent in just three years. The 15 American League teams alone hit 3,170 home runs, more than all 26 MLB teams in 1992.

The committee’s research found that the change was not because of an increase in batters’ contact coming with a higher launch angle, which would have signaled that more batters were hitting the ball in the air — and gunning for the fences.

Instead, what the committee found was that baseballs are flying farther because they aren’t experiencing as much friction in the air, which the panel dubbed “drag coefficient.”

“The thing we learned is that there appears to be less of a drag on the ball,” Albert said. “The balls that were hit at a certain launch angle and launch speed were carrying further than they were the previous year or two.”

What the panel does not know is why.

Albert said a few committee members visited the factory in Costa Rica at which the MLB baseballs are made, and they came away impressed with the process and its overall quality control. In other words, there was no obvious problem with the manufacturing of baseballs.

The committee recommended two things to MLB: more testing and for baseballs to be stored in climate-controlled environments similar to the “humidor” at hitter-friendly Coors Field at high altitude in Denver.

That MLB turned to academia to better understand its game in the first place is not lost on the researchers from many disciplines who focus their craft on sports data.

Ben Baumer, a former statistical analyst with New York Mets who has collaborated with Albert in the past, said the BGSU professor deserves credit for the popularization of sports research from academics.

“People like Jim are really pioneers in terms of making sports analytics legitimate as an academic discipline, which I think it is,” said Baumer, who now is an assistant professor of statistical and data sciences at Smith College in Massachusetts. “But it wasn’t always viewed that way.”

Mark E. Glickman, a senior lecturer on statistics at Harvard who worked alongside Albert at the Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports, recalled disguising research headlines so they did not sound sports-focused.

In one 1999 paper that came up with an alternative to the Elo algorithm — which he applied to tennis and chess — Glickman went with “Parameter Estimation in Large Dynamic Paired Comparison Experiments,” and was tickled it didn’t sound like he had spent so much time looking into sports.

“I’m kind of proud I came up with such and obscure-sounding name,” Glickman said with a laugh. “That was the nature of academics back then.”

Combining baseball and data came naturally to Albert, who grew up in Philadelphia and has carried a lifelong love of the Phillies.

With baseball in particular, data sets are clean, readily available, and often free, and Albert said applying his mathematical knowledge fit. His most recent book, Visualizing Baseball, came out last summer.

“It was sort of an easy thing because I’ve always been a sports fan, especially in baseball, so I always had the fan interest, and I’ve always been fascinated with statistics and data,” Albert said.

Before the analytics movement became a multi-sport phenomenon, Albert was one of the researchers producing detailed analyses on baseball.

And with the help of researchers like Albert, Glickman said the academic focus on sports has changed.

“He’s an incredibly respected researcher,” Glickman said of Albert. “He really is, in some ways, the godfather of sports statistics. He was one of the early adopters of being somebody who took sports statistics seriously.”

Contact Nicholas Piotrowicz at npiotrowicz@theblade.com, 419-724-6110 or on Twitter @NickPiotrowicz