Undefeated UT quarterback still denied final victory

7/11/2010

Chuck Ealey led the University of Toledo Rockets to a 35-0 record over three seasons at the institution. Because Ealey wasn't named an All American by an accepted major organization, he is ineligible for consideration for the College Football Hall of Fame, despite his unmatched perfect record.

There are 126 quarterbacks in the College Football Hall of Fame, including Louisiana Tech's Terry Bradshaw, Ohio State's Rex Kern, Mississippi's Archie Manning, and Stanford's Jim Plunkett, Jr.

They all played in the same era that Chuck Ealey did at the University of Toledo (1969-71). None of them went undefeated, but they're in the hall, and Ealey is not.

In three seasons at UT, Ealey had the remedy every time the Rockets faced adversity. He led them to 35 straight victories as the starting quarterback - a record that has never been duplicated across the landscape of major college football.

Ealey was Houdini and Baryshnikov in spikes and a helmet. He mastered creative deception at the quarterback position as his bait-and-switch routines left defenses staggering.

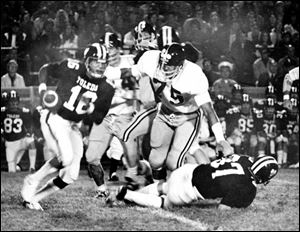

Chuck Ealey

Ealey and the Rockets won three Mid-American Conference championships, had three bowl victories, and put together three straight undefeated seasons. On the football field, he could do anything.

He just can't get into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Because of some strict criteria put in place sometime after Ealey graduated from UT, he is not even eligible to be placed on the ballot for the hall to let the voting members of the National Football Foundation determine his worthiness. Bureaucracy, unintended consequences, archaic directives, or even latent prejudice - all of those explanations have been offered up by those upset over Ealey's status with the hall. The powers that be inside the foundation vehemently deny any of that is accurate, saying the rule is the same for everyone.

"If they can't fix that, it's a shame," former Purdue head coach and Toledo native Joe Tiller said about the exclusion of players such as Ealey and Tiller's former standout quarterback, Drew Brees. "It's political, but unfortunately, that doesn't gauge performance."

University of Toledo quarterback Chuck Ealey scrambles during a 1971 game.

Ealey gets thrown for a loss by the College Football Hall of Fame rule that states that any candidate has to have "received major first-team All-America recognition." Ealey was named first team by the Football News, which at the time was not part of the All-American teams approved by the hall.

Now, almost 40 years since Chuck Ealey last dazzled Rockets fans as "The Wizard of Oohs and Aahs," he is still on the outside. The shrine established to honor the game's greatest players does not consider him a viable candidate for membership.

"I would think that anybody who went 35-0 would be someone you want in your hall of fame," current Toledo head coach Tim Beckman said. "Chuck Ealey and what he represents - we tell our kids that is what college football should be about. He won, and he did it with class. That's got to be worth something."

Chuck Ealey grew up in a third-and-long environment, in the projects in Portsmouth along the Ohio River. His parents divorced very early in Ealey's life, and his mother, with just an eighth-grade education, raised and supported the family.

His only brush with trouble came during a protest against Portsmouth's "Whites Only" municipal swimming pool. Ealey attended Notre Dame, a predominantly white Catholic high school, waxing the floors to earn his tuition.

He led Notre Dame to consecutive undefeated seasons and the school's first state championship. "When he walked on the football field, he was in charge," Notre Dame coach Ed Miller said in an award-wining documentary on Ealey's life.

At the end of his high school career, Ealey encountered a stubborn and heavily entrenched opponent - the conventions of the time sentenced most gifted black athletes to play defensive back or receiver in college. Ohio University and Miami University (Ohio) both showed interest, but they intended to play Ealey at defensive back.

"I was a quarterback, and that's what I wanted to play," Ealey said. "I decided to find the right opportunity for me."

Toledo coach Frank Lauterbur heard about the Notre Dame quarterback and sent an assistant to watch Ealey play in a basketball game, during which Ealey hit a midcourt shot at the end to give his team the victory.

"We felt like there was something special about this young man, so we decided to take another look at him," Lauterbur said.

Ealey and high school teammate and offensive lineman Jim Goodman visited the UT campus. Lauterbur offered them both scholarships and also promised Ealey the opportunity to play quarterback.

"We ended up going to Toledo, and the rest is history," Goodman said.

History, indeed. Lauterbur kept his word, and when an Ealey-led offense was combined with the top defense in the country, three seasons of perfection followed.

Freshmen could not play on the varsity at the time, and when Ealey prepared for his sophomore season he was situated behind an established senior quarterback who was coming off a successful season. When that player was injured in a scrimmage, Ealey got his opportunity to play.

In his first season as a starter with the Rockets, Ealey's team was down 17-0 at rival Bowling Green, but he rallied the Rockets for a historic win. "At that point, I think it became my team," Ealey said. The Rockets piled up the wins, with some aided by Ealey performing heart-stopping heroics as the final seconds ticked off.

In 1970, following a second-straight unbeaten season, the Rockets routed a William & Mary team coached by the now legendary Lou Holtz. The following year, early in the season in a tight game against Villanova, Ealey threw a long pass to set up the winning score in the closing moments.

"That was really Chuck Ealey at his best," Lauterbur said. "Those guys would march into battle with him, confident he would find a way to win. And he always did."

After a 28-3 win over Richmond in the Tangerine Bowl to close the 1971 season, Chuck Ealey's 35-0 run as Toledo's starting quarterback was complete, and his place in college football history cemented.

The NFL, a place where black quarterbacks were still a rarity, ignored Ealey in its draft. He went to the Canadian Football League and promptly led Hamilton to the Grey Cup game, Canada's Super Bowl, as a rookie. He took his team to victory in the closing moments in a manner many UT fans found familiar and was named the MVP.

A collapsed lung ended his pro football career after seven seasons, and Ealey, now 60, settled with his family in Toronto, where he has been a successful businessman and community leader.

Chuck Ealey played a violent sport at a very volatile time in American history. He grew up in a mostly segregated Portsmouth. When he came to the University of Toledo, Chuck Ealey came as a quarterback, leading a team of mostly white players.

"It was a very different time," Ealey said about his arrival at UT in 1968. "We had players from all over, and some of them, I don't suppose, had ever played on the same team with black players. But once we put on the uniform, there was some commonality there."

Ealey displaced white starting quarterbacks in high school and again in college, yet he said he sensed no overt opposition to the moves. "I honestly feel that when we were on the field it was just a team - we didn't see colors."

Ealey has never raised the issue of race concerning his status with the hall of fame or any other football-related topic. Given the era he played in, others familiar with the situation contend that it is reasonable to at least address the question.

Jack Taylor is an associate professor emeritus of ethnic studies at Bowling Green State University, and a former college athlete from the same period.

He said that because black quarterbacks were very rare at the time, race might have played a role in Ealey being left off some All-American teams.

"Given the climate at that time, it is certainly something to be considered," Mr. Taylor said. "You have to wonder if some voters just did not name Chuck Ealey because they were not ready to accept the fact that a black could play the position, and play it extremely well."

Because most of the electorate on those All-American panels from nearly a half century ago are deceased, that uncomfortable question will persist.

There are a number of black quarterbacks in the College Football Hall of Fame - Major Harris, Andre Ware, Charlie Ward - but had Ealey been eligible for consideration and voted in, he would have been the Hall of Fame's first black quarterback. That distinction belongs to Doug Williams, who played at Grambling, a historically black college, from 1974-77 and was voted into the hall in 2001.

The College Football Hall of Fame is in downtown South Bend, Ind., near the University of Notre Dame campus. It was established almost 60 years ago by the National Football Foundation, which provides its operation, support, and administration.

The approximately 12,000 members of the foundation can nominate players for consideration for the hall of fame. If a player meets the criteria laid out by the foundation, he must then be approved by a screening committee, win enough votes for consideration, then be one of about a dozen each year chosen by the NFF Honors Court for enshrinement in the hall of fame.

Many of the hall's 882 current members were inducted before the strict criterion was put into place that mandated a player be a first-team All-American by an NCAA recognized entity.

Ealey was named first-team by The Football News, which was not on the approved list at the time, but later was added. Each time Ealey has been nominated to appear on the ballot, he has been rejected based on that initial criterion.

That rule appears to also exclude from consideration for the hall such prolific college players as Joe Namath, Joe Montana, Drew Brees, Bernie Kosar, Brady Quinn, Tyrone Wheatley, and Eli Manning.

Steve Hatchell, president & chief executive officer of both the National Football Foundation and the College Football Hall of Fame, said his organization has strictly adhered to that measure "since 1990."

Hatchell, who was the first commissioner of the Big 12 Conference, said any organization needs guidelines. "A lot of significant people in football are not in the hall because they are not eligible," he said. "You've got to have some rules, and stay with it. Right or wrong, you have to have some cutoff."

However, it appears that the proviso requiring top All-American status by an approved entity was overlooked in at least one very prominent case before 1990.

Former Mississippi quarterback Archie Manning played in the same era as Ealey, was inducted into the hall in 1989, and is chairman of both the hall and the foundation. His official biography makes no mention of any approved All-American status.

Hatchell, who was not in his position with the football foundation at the time, had no explanation for how Manning got into the hall.

When pressed on the subject of Ealey or others, Hatchell said he understands the passion of those who support prominent former players being considered for the hall.

"Absolutely - I understand he was a terrific player. Chuck was a great player. I was in college at the time. There's others that we'd love to get in, but these lines have been drawn up, and we have to be faithful to it."

Some of the critics of the hall of fame's policies say the hall "digs in its heels" when approached about possible rule changes.

Hatchell said it is his job to "be faithful" to the lines as they were drawn up. "There are almost 2,000 guys eligible right now, and we only take about a dozen a year," Hatchell said.

The football foundation has resisted changes, often citing a concern that such moves would "open the floodgates" and deluge the group with nominations. Not everyone buys that.

"If you put in place a rule that says that every guy who goes undefeated as a starting quarterback for three straight seasons will be considered for the hall, I don't think you'd open the floodgates," Mr. Taylor said. "I think there would be one guy - Chuck Ealey."

One proposal that has been floated calls for any player who finished in the top 10 in voting for the Heisman Trophy or one of the other major awards be eligible for nomination. Ealey was eighth in the Heisman vote as a senior.

Tiller and others stated that change will most likely have to come through the football foundation's membership and its system of chapters. "There has to be a way to fix this," Tiller said

Lauterbur said he hopes what he calls "a real injustice" done to Chuck Ealey is rectified soon.

"That was 40 years ago that Chuck played, and the folks that coached him and knew him best, they're not going to be around forever. I'd really like to see him get in there before much more time goes by."

Contact Matt Markey at:

mmarkey@theblade.com

or 419-724-6510.