TOLEDO MAGAZINE

Remembering a journey 'into absolute nothing' in Antarctica 70 years ago

A 1946-47 expedition led by Rear Admiral Byrd included Maumee’s Edward Becker

9/29/2013

Edward Becker, at his Maumee home, said he saw many things in his six years in the Navy, including the aftermath of atomic bombs dropped on Japan. His journey to Antarctica with Admiral Byrd in 1946 is his favorite memory.

The Blade/Andy Morrison

Buy This Image

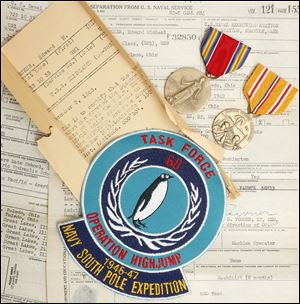

Service papers, medals and a mission patch belonging to Edward Becker at his Maumee home, Friday, Sept. 13, 2013.

The nearly 70 years since Edward Becker ventured to Antarctica have not tempered his recollection of the cold. It bit hard, like a thousand needles pushed by a relentless wind.

“It surrounded you, all the time. The wind and the cold were always there,” Becker said recently. “It made everything much more difficult, even the simple things.”

Becker, a native of Toledo and a Waite graduate, was part of the historic “Operation Highjump” expedition to the frozen continent in 1946-47, led by iconic explorer Admiral Richard Byrd.

“We went off into absolute nothing,” the 91-year-old Becker recalled about the ambitious venture to Antarctica, the most remote, hostile and inaccessible location on the planet. “They never really told us what we were doing there. I still don’t know for sure.”

Byrd took 13 ships, multiple aircraft and more than 4,000 men along, and most of those men were Navy sailors, like Becker. In his writings, Byrd outlined the ambitious agenda he had for the team.

“It was hoped that in a few weeks, more would be learned of the great unknown than had come from a century of previous exploration by land and sea," Byrd wrote of his fourth expedition to Antarctica.

“There were a lot of ships in the group that went down there, but we were the only destroyer,” said Becker, who after serving in both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters during World War II was on board the USS Henderson, and was responsible for the operation of its big guns. “The other ships were tankers with extra fuel, supply ships, and smaller vessels that could move in close.”

Becker and the Henderson arrived in Antarctica around Christmas of 1946, which put them on the coldest and windiest continent at the warmest time of year, when the average high temperature is around minus-20 degrees.

“Once we passed the tip of South American, we started to see ice,” Becker said. “It was my first experience with ice at sea, so I was a little concerned. The further south you went, the ice bergs got bigger, and the ice jams were everywhere.”

While Byrd’s expeditionary groups went on scouting forays or photographed large sections of Antarctica from the air, Becker spent most of his time on board the Henderson, working to keep the ship’s guns operational.

Edward Becker, at his Maumee home, said he saw many things in his six years in the Navy, including the aftermath of atomic bombs dropped on Japan. His journey to Antarctica with Admiral Byrd in 1946 is his favorite memory.

“Those guns worked with hydraulic fluid, but nobody knew if they could function in those kinds of extreme temperatures,” Becker said. “I was the only one on board who got their guns to fire when it was 50-below, and at 50-below zero, hydraulic fluid is like Jell-O. I fired over 20 salvos at the ice bergs.”

While Becker’s ship provided support, security and weather information in the brutally harsh environment, other vessels were involved in even riskier operations. An aircraft carrier had taken small planes to the perimeter of the ice floes, and from there they made the treacherous flight to a crude landing strip laid out on the edge of the shelf ice.

“Usually, there was ice as far as you could see,” Becker said. “There were ice bergs taller than the buildings in downtown Toledo, and they were huge. Some of them had to be bigger than the city of Maumee. We didn’t get too close to them for fear they would rip the ship in half.”

Becker said the working wardrobe on board the Henderson included heavy dungarees, thick wool jackets, wool pants, wool socks with high-top boots, with a second pair of insulated boots worn over those. He ordinarily worked while wearing three pairs of gloves, a face mask and goggles.

“The storms were almost continuous, so there was water flying everywhere, but if that water hit your skin, it would freeze your nose, lips or ears in an instant,” Becker said. “You just had to be so careful, because you could get frozen fingers right away. And if you took your gloves off and reached for anything iron, you wouldn’t get your hand back.”

Becker said the sailors were responsible for protecting themselves from the elements.

“If you got frost bite, it was your own fault and you got court-martialed,” he said.

The bunks below were stacked with heavy blankets, and although that area of the ship was heated, the cold seemed to creep in everywhere, pushed by the wind.

“I never experienced wind like that,” Becker said. “Even on the calm days, it wasn’t calm.”

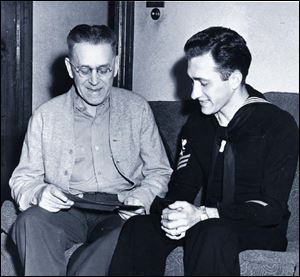

Edward Becker shares his military papers with his father. Mr. Becker corresponded often with his family during his more than five years at sea.

Their diet was plain and monotonous, with no ice cream and no beer, Becker recalled. It was usually boiled beans for breakfast, and chicken the rest of the day.

“And soup. We had lots and lots of soup,” Becker said.

Becker said he saw whales and penguins, but very little else in terms of animal or plant life.

“It was beautiful, in its own way,” he said of Antarctica and its 5.5 million square miles of ice. Operation Highjump logged some 70,000 aerial photographs of Antarctica, and those were later used to map large areas of the continent.

“I was a 20-year-old kid when I joined the Navy, and here I was just a few years later, in a place few men had ever seen before. It was an adventure I haven’t forgotten.”

Contact Blade outdoors editor Matt Markey at: mmarkey@theblade.com or 419-724-6068.