Ex-con Jimmy Santiago Baca found hope, purpose, passion for writing while in prison

9/28/2013

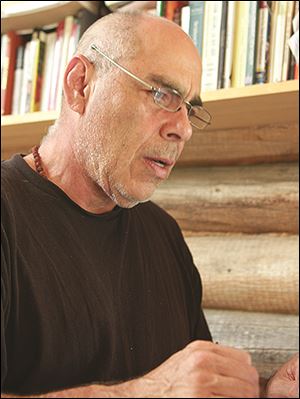

Jimmy Santiago Baca

Maximum security prison — with the terror of watching his back, vicious knife fights, and long stretches in isolation cells — is where Jimmy Santiago Baca spent his 21st through 26th years.

It wasn’t a surprise; he was a dead-end kid, abandoned by poor parents and raised by grandparents until he was 7 when they took him and his brother to an orphanage. At 13 he ran away, quit school, and lived on the streets. Selling drugs was lucrative, but when he tried to quit he was set up, busted, and after escaping a gun battle with the FBI, he turned himself in.

Despite its brutality, prison became his salvation, the place where he learned to read and write, discovering passion and talent for the written word.

Now 60 with a fine home in Santa Fe, five children ages 6 to 29 he had to learn how to hug, “married to a beautiful woman” (Stacy James), and a cabin in the northern canyons that were painted by Georgia O’Keefe, Baca makes his living creating poetry and books and speaking. He’ll take the stage at 7 p.m. Wednesday in the McMaster Center at the Main Library as part of the Authors! Authors! series cosponsored by The Blade and the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library.

“I’d like to read poetry and talk about the background of the poems and different styles and some of the life experience of the poems,” he said.

As he usually does when he speaks, he will meet prisoners at the Toledo Correctional Institution on Tuesday and with up to 200 Toledo youngsters at a Books 4 Buddies event at the Believe Center in South Toledo on Thursday.

A Place to Stand, his searing 2001 memoir of childhood and imprisonment, won the prestigious International Prize. He’s also written A Glass of Water, about illegal immigrant brothers; Adolescents on the Edge, an approach for reaching at-risk adolescents; Stories from the Edge, more about his early life and prison years, and poetry including Breaking Bread with the Darkness: Book 1: The Esai Poems, and Winter Poems Along the Rio Grande.

After his release from prison in 1979, he vowed never to return, until the day he was offered $20,000 to speak at one.

“When they brought the prisoners in, some guy said to me ‘You’re only doing this for the money.’ He was wrapped in waist chains and ankle chains. I said, ‘Yup, you’re right.’ I didn’t want to be there,” he said in a telephone interview from his home. “That night I couldn’t sleep. The next day I went back and asked to do a writing workshop. ... These men reminded me of this thing called gratitude, for everything I have I was given through writing. It began to reinforce that I needed to go to these facilities.”

He’s conducted hundreds of writing workshops since.

Even after prison, nothing about his family of origin was easy. When his mother planned to leave her husband, he killed her with a shot to the face. His brother’s body was found in an alley, his skull crushed by a pipe. His first girlfriend died from a drug overdose. His father choked to death after leaving a treatment center. Part Mexican, part Indian, Baca advocates not only for prisoners but for some of the issues linked to incarceration: mental illness, drug addiction, and homelessness.

Prisoners have “remarkably despairing lives,” he said. Acting out of moral obligation, he has visited countless prisons. A few weeks ago, after a talk at Stanford University, he went to a youth detention center and met a boy who’d just turned 16 and is facing 27 years. “He reminded me so much of the young Jimmy. He was so charismatic. I said, ‘Please use it to be a leader.’ I told him I’d write him a letter a month and send him books.”

Prisons don’t rehabilitate, he said: “There’s nothing that facilities do but destroy lives.”

His efforts to get people behind bars to do the right thing have failed time and again, but he knows at least three things that can save lives before they’re lost.

One is doing whatever it takes to make sure kids can read and write.

Another: centers that train people to be youth mentors. “That means that people like me have to step the step and walk the walk. The community has to step in. We built prisons with our tax dollars, but we have to offer alternatives. ... We have recycling centers. Why can’t we recycle destroyed human beings?”

The third is providing at-risk youth with paying jobs. “Put him in a bicycle shop instead of stealing bikes. Let these kids go to the dog pound and train dogs to give to people. It’d be so cool to give these kids some monetary way to prove their worth. That was one of the only things that worked for me.”

Baca’s routine begins at 5 a.m. when he rises for an hour of meditation, making breakfast for his wife and the two youngest children, and walking them to school. Then he writes in his home office for two to four hours, until he tires. “I’m not a saint. I struggle every day. My writing keeps me strong.”

The work — crafting a clear sentence — is a joyous labor of love. “I don’t think about the reader. I think about the integrity of the work itself.”

Baca loves hiking, fishing, harvesting firewood, and gardening. “I like planting trees and rocks and cactus.” He was searching for a spring near his cabin recently when he discovered a cache of Anasazi pottery. “Pots and beads and arrow heads. And I buried it back up. I felt it wasn’t mine to take.”

“I tend not to be a social person. I tend to hang out with my family.”

He’s wrapping up several books. Face is part of a project in which writers in a dozen countries have been commissioned to write about their faces. He found it an easy topic. At the age of 5, he was running hard for a ball and hit a tree. “I went into a coma and I was disembodied. I was looking down at myself. There was my astral face and my physical face. And as I went through life, in poignant moments when my spirit was up above, there was the face again. It became a sort of guardian for me.”

To be published in January is Singing at the Gates, stories, essays, letters, and poems. Frog King is the sequel to A Place to Stand, “1979 to 1983, from when I got out of prison to the birth of my first son.”

And, he and two others are working on a curriculum and year of lesson plans for adolescents who don’t like to study and read. “It’s how I get kids to go back to school and excel.”

Jimmy Santiago Baca will speak at 7 p.m. Wednesday in the Main Library, 325 N. Michigan St. Admission: $10 adults/$8 students.

Contact Tahree Lane at: tlane@theblade.com and 419-724-6075.