ENTERTAINMENT

The genuine voices of midcentury fiction

2/4/2014

Harry and Lynne Sharon Schwartz built a roster of authors in 1963.

Harry and Lynne Sharon Schwartz built a roster of authors in 1963.

Just over half a century ago, Harry Schwartz, a city planner, and his wife, Lynne Sharon Schwartz, an editor at The Writer magazine, were sitting in their Boston apartment with friends and talking about American fiction.

J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey had just come out. John Updike and Philip Roth were getting under way with their first books. Writers like Norman Mailer, William Styron, and James Baldwin were hitting their stride.

A question arose: What did these people actually sound like? No one knew.

Public readings were not nearly as common in 1961 as they are today, and the two main spoken-word record companies, Caedmon and Spoken Arts, concentrated on heavy hitters like T.S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, and W.H. Auden. Lesser known and younger writers, by and large, were silent presences.

The Schwartzes sensed an opportunity. Why not invite a few favorites to record excerpts from their work, and then sell the performances in bookstores and record stores?

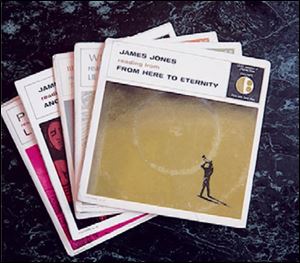

So began the brief life of Calliope Records, a series of 7-inch 33 1/3-rpm discs, released in 1963 for $1.95 each, offering 15-minute readings by Updike, Styron, Baldwin, Bernard Malamud, James Jones, and Peter Ustinov. The series is now being reissued, under the title “Calliope Author Readings,” on two CDs and downloadable audio files.

The readings arrive like errant postcards delivered decades after the fact. The effect can be eerie. Updike, tiptoeing his way through the intricate syntax of Lifeguard from his short story collection Pigeon Feathers, sounds impossibly youthful and fey. It takes an effort to recall that the owner of the voice died in 2009.

With the exception of Roth, who gives a spirited, richly comic rendition of a scene from Letting Go, the other readers are dead, too, lending a time-travel aspect to the enterprise. Malamud, reading “The Mourners” from his story collection “The Magic Barrel,” uncorks the kind of Brooklyn accent that left the borough around the same time that the Dodgers headed for Los Angeles.

Newly released readings take listeners back in time.

Baldwin brings a refined theatricality to passages from “Giovanni’s Room” and “Another Country,” a contrast to the more muted style of Jones, reading from “From Here to Eternity,” and Styron, reading from “Lie Down in Darkness.”

Nelson Algren was taped after the original series came out. After rediscovering the reels in a closet in their apartment last year, the Schwartzes edited his performance and included it in the reissue. Talking tough out of the side of his mouth, Algren finds a jazzy groove reading excerpts from “The Man With the Golden Arm,” with a hypnotic recitation of “Epitaph,” the poem that ends that novel.

The entire Calliope venture was a shot in the dark. The Schwartzes, joined by Howard Kahn, a colleague of Harry Schwartz’s at the Boston Redevelopment Authority, put together a seat-of-the-pants operation.

The three partners rounded up the writers and organized the recording sessions with a local sound engineer, Stephen Fassett, who worked with the Harvard Glee Club and recorded a number of local folk singers, Joan Baez among them. When 15,000 album sleeves were delivered from the printer, the Schwartzes and Kahn, who died in the mid-1970s, held pasting parties to fold and glue them.

Target No. 1 was Baldwin, scheduled to speak at MIT. The Schwartzes waylaid him after the lecture, gave their pitch and, after getting a definite maybe, successfully wooed his agent.

It was certainly not the money. Calliope offered $50 for the recording and a $100 advance against sales.

“I think that because it was such an unusual project, they were flattered,” Lynne Schwartz said.

Baldwin knew Styron, and Styron knew Jones, allowing the Schwartzes to build a roster by following a chain of friendships.

There were rejections. Carson McCullers was too ill. Marianne Moore said no. Norman Mailer demanded 10 times the fee offered to the others. “We had several letters from Salinger, declining the invitation at different levels,” Harry Schwartz said. The letters were later lost.

The writers who agreed tackled an unfamiliar medium in a variety of styles.

“Baldwin was a natural,” Lynne Schwartz said in an interview in the couple’s apartment near Columbia University in New York. “Malamud did not seem to have such a good time, but he did fine. Updike was self-effacing and unpretentious.”

Jones found it difficult to get through the lyrical, elegiac passage in “From Here to Eternity” in which Robert E. Lee Prewitt plays “Taps” for his dead friend, Angelo Maggio. “He was almost on the verge of tears,” Harry Schwartz said. “It was very emotional, that reading.”

Roth, who read narrative passages from “Letting Go” in a gentle, reedy voice, kicked into high gear rendering the Yiddish-inflected dialogue of Levy and Korngold, two old men in a run-down rooming house.

“He was 30, still young,” Harry Schwartz said. “Now, at readings, he’s less forthcoming, but then he was a performer, the life of the party.”

Lavish praise from the poet John Ciardi in The Saturday Review, and a nice push by The Atlantic Monthly, sent Calliope on its wobbly way into the marketplace, where it reaped glowing reviews and modest sales before sputtering to a halt not long after Harry Schwartz took off for Rome on a Fulbright grant.

Although most of the records sold, Calliope wound up a few thousand dollars in the red. Kahn’s parents paid off the debt.

“The authors earned out their advances, although it was sort of embarrassing sending out the royalty checks,” Lynne Schwartz said. The amounts, Harry Schwartz said, were “modest — $12.87 or something like that.”

For the reissue, the Schwartzes dropped Peter Ustinov, who had read from his novel “Loser,” reasoning that he is remembered today primarily as a raconteur and public wit. To make up the shortfall, they included the Algren material, and a recording by James Jones from “The Thin Red Line,” contributed by his daughter Kaylie Jones.

There were lost opportunities. Despite pledges made on the original record sleeves, Calliope never did get around to recording Archibald MacLeish, Howard Fast, C. Northcote Parkinson or Lotte Lenya.

The lack of a woman on the list, Lynne Schwartz said, “has been a thorn in my side over the decades.” On the other hand, she said, “This time we didn’t have to glue anything.”