National DNA database helps crack cold cases

In cases with few clues, system can be gold mine

9/1/2014

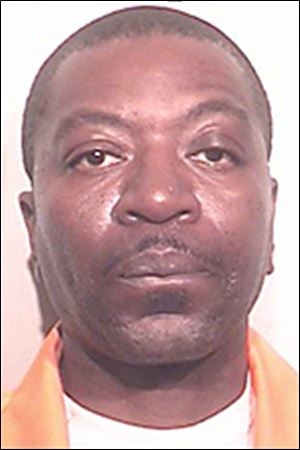

Beamon

For more than a decade after he broke into a Toledo home, raped and hogtied a woman who’d been asleep in her bed, Aaron Lamont Beamon got away with the violent crime.

Beamon

It would take time and the nation’s massive database of DNA samples to catch up with Beamon.

Lingo

Now 39, he is to be sentenced Sept. 9 in Lucas County Common Pleas Court after pleading guilty in June to rape, kidnapping, burglary, and robbery in connection with the Oct. 15, 2001, attack on the 21-year-old victim.

DeWine

“She was living with her parents at their home,” said Jennifer Liptack-Wilson, an assistant Lucas County prosecutor assigned to the case. “Everyone had left for school and work, and she was in bed sleeping.”

The victim didn’t know her attacker and wasn’t able to see his face.

“We were never able to find him, but we came to find him because vaginal swabs were taken as part of a rape kit, entered into [the DNA database], and finally we got a hit,” Ms. Liptack-Wilson said.

In cases with few other clues to go on, it can be like hitting the lottery.

“We see these miracles every day,” said Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine, whose office oversees the testing of DNA evidence through its Bureau of Criminal Investigation.

He has been working to have police across the state submit untested DNA evidence from unsolved sexual assaults to BCI for testing.

“It’s just amazing because it works both ways: It can clear a suspect out of an investigation … and the other side is all of the cases we can solve because of DNA,” Mr. DeWine said.

In Beamon’s case, court records show that in 2012 he was seen breaking into a car and stealing a purse in a Monroe Street parking lot. In the process, he cut his hand, and when the purse was recovered by police, it was submitted for DNA processing.

Not only was Beamon identified as the purse thief, his DNA profile matched semen collected in a rape kit from the 2001 unsolved case — evidence that was included among the “unknown profiles” contained in the FBI’s nationwide database known as the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS.

Confronted with the DNA evidence by Toledo police, Beamon confessed.

“It started the ball rolling really fast,” Beamon’s attorney, Joe Urenovitch, said.

Jeff Lingo, chief of the criminal division for the Lucas County Prosecutor’s Office, said the first case he prosecuted that came from a nationwide database hit involved Bradley Roberts, a Toledoan convicted by a jury of sexually assaulting a 10-year-old girl near Arbor Hills Junior High School in Sylvania Township.

The crime occurred in 1993. The DNA match came in 2010. Roberts was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison in 2011.

“It used to be when a case was that old, chances are you were never going to be able to solve it,” Mr. Lingo said. “Now with the advent of DNA, it increases the solvability of cold cases.”

And the database has grown exponentially in recent years.

Ohio began collecting DNA from inmates sent to prison for felony convictions in the mid-1990s. In 2000, it joined CODIS, and five years later a state law went into effect requiring that all Ohioans convicted of felonies and some serious misdemeanor offenses submit a DNA sample.

In 2011, a new state law went further, requiring that DNA samples be taken from all adults arrested for felony offenses.

According to CODIS, more than a half-million DNA profiles from Ohio are in its database, including 447,534 from convicted offenders and 112,652 from those arrested for felonies. An additional 37,927 unknown profiles linked with crime scenes also are in the database awaiting a match.

So far, CODIS hits have helped 9,590 investigations in Ohio.

“The biggest change in law enforcement in my lifetime really has been the availability to collect unknown DNA and to match it up with known DNA,” said Mr. DeWine, a former prosecutor in Greene County. “That has just revolutionized what police do.”

Juries tend to put a lot of stock in DNA evidence, he said, although it doesn’t always ensure a conviction.

“Prosecutors call it the CSI effect,” Mr. DeWine said. “And that can cut both ways — juries expect DNA, and sometimes there is no DNA.”

Particularly in cases of sexual assault, though, DNA evidence is often very solid.

“It’s unlike hair where it’s similar,” he said. “DNA is a match. Juries take it very seriously. They believe in it.”

Contact Jennifer Feehan at: jfeehan@theblade.com or 419-213-2134.