Attachment disorder torments some children, adoptive parents

11/16/2013

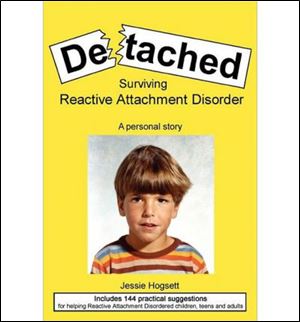

Jessie Hogsett

As a child, Jessie Hogsett was almost impossible to parent.

Neglected and abused by his alcoholic birth mother, he was 5 when he arrived at the home of the childless California couple who would adopt him. They were educated, had big hearts, and offered him boundless affection, stability, and opportunities — gifts Jessie couldn’t receive.

He was stealing by 7, lying, cutting holes in his clothes, turning away when his mother tried to kiss him, and destroying the things she gave him. He despised that they had rules and told him to make his bed, help with the dishes, and do homework. He was hyper, couldn’t make friends. He stole more.

“I wasn’t worried about getting caught or even if I was hurting anyone. I just wanted what I wanted and I wanted it now!” he wrote in his 2011 book.

He cut himself, slept with a knife under his pillow. “I think I probably would have used it on my parents,” he said in a telephone interview. At 13, he obsessed about suicide and guns. His parents removed knives from the kitchen, which pleased him.

“I was scary to them. That made me powerful. In essence, I was now in absolute total control.”

Mr. Hogsett, 33, knows now what none of them knew then. He has Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD), a rare but serious condition caused when infants and young children don’t establish healthy bonds with parents or caregivers. They’re neglected, abused, or orphaned, and their needs for comfort, affection, and nurturing are unmet. Without loving attachments with others they may grow up to be extremely troubled, even sociopathic, adults.

-- Adopt America Network: 419-726-5100.

-- Facebook, Adopt America Network’s Support Group.

-- Attachment and Bonding Center of Ohio, abcofohio.net, specializes in the treatment of children and adolescents who have had problems because of trauma early in their lives. Its founder, Gregory C. Keck, has published books on the subject.

-- Project H.O.P.E. equine therapy in Bowling Green and Findlay, www.projecthope-equinetherapy.com.

Mr. Hogsett will speak and answer questions about how he became able to bond with others from 1 to 4 p.m. Saturday at the Funny Bone Comedy Club at Levis Commons, 6140 Levis Commons Blvd., Perrysburg. Tickets are $10 for the program organized by Adopt America Network, a national adoption group based in Toledo that helps children in the U.S. foster-care system find permanent, loving families. Also this week, an evening program for parents of adopted children with RAD will be Wednesday and Thursday, Contact Adopt America Network for details at 419-726-5100.

Detached

“A lot of people still don’t understand RAD,” said Mr. Hogsett from Modesto, Calif., where he works as a merchandise technician at Home Depot and attends college. His journey to connection continues with his supportive wife, Brenda, and took perhaps its greatest leap when his children (five, from newborn to age 12) were born and he vowed to create a secure and loving home for them.

In his 2011 autobiography, Detached: Surviving Reactive Attachment Disorder, he relates how he was so dangerous by 13 that his frantic parents placed him in a residential treatment facility, for which he didn’t forgive them for many years, but where he received valuable help. Three years later he ran away and lived unhappily with the adoptive families of his birth sisters until 18, then moved into his own place and became a teen dad. He attempted suicide but gradually turned things around.

“I don’t think there’s enough help out there for these adoptive families,” he said. In his book, he lists 144 suggestions for helping children with RAD. The third is “Do not knowingly adopt a RAD child if your life isn’t already filled with love. You won’t get the love you’re seeking from a child unable to give it, at least [not] for a very long time.”

The struggle

Gregory Keck treats children and adolescents like Jessie who’ve had early trauma, which can include deafness before it’s diagnosed. Most kids with attachment problems are immature, he said.

“Families really struggle because very few people understand this diagnosis and how extremely difficult it is for families to live with,” said Mr. Keck, who established the Attachment and Bonding Center of Ohio in Cleveland and has written books on the subject. In years past, adoption agencies may not have known about or divulged the extent of a child’s troubled background or behavior, and even today, some international adoption agencies may not provide full disclosure, he said.

RAD can be expressed in two ways: a child can be withdrawn, not affectionate, and listless, or they can be inappropriately friendly to strangers, have severe tantrums, steal, lie, manipulate, set fires, and hurt small animals. It’s a relatively new diagnosis, and children are often given other diagnoses, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or bipolar before RAD.

“It’s really hard to get a good diagnosis,” said Cheryl Reber, a Cincinnati consultant specializing in childhood abuse and neglect. Normally, when a baby cries, an adult comes and makes their discomfort go away. But when nobody comes or if the person who comes hurts the baby, she or he can’t predict what might happen; they’re unable to trust, she said.

Raising a child who has RAD can take a toll on their caregivers.

“Often, the parents need medications because they become clinically depressed,” she said. Siblings may be forgotten victims, because their parents’ time, energy, and financial resources is focused on the troubled child.

Temper tantrums

With two biological children ages 9 and 6, good jobs, solid grounding in their religious faith, and love to share, Leslie and Steve Haton of Swanton met 5-year-old Torie through Adopt America Network. After being removed at the age of 2 from his abusive, neglectful birth mother, he’d lived in more than eight foster homes. He was angry, easily frustrated, and diagnosed with ADHD and mood disorder.

“From what I read, he had glorified temper tantrums,” said Mrs. Haton, who has a background in social work. “If he got too challenging, foster parents would put in a 30-day notice and ship him off.”

He was almost 6 when they adopted him. Blond and blue-eyed, he is charming, outgoing, creative, funny, and can build anything with LEGOS. He is 11 years old, but emotionally, he’s at about a 6 or 7-year-old level.

He didn’t play with other kids. He hugged strangers, dug through the trash for food, and had an attention span of eight seconds. When parents at his day care complained about his behavior, Mrs. Haton quit her job to take care of him.

“We couldn’t go anywhere with him,” she said. “He was kind of like a wild child.” He’s thrown chairs, knocked down doors, banged his head on the wall, and dropped books on her head when he was upstairs and she was downstairs. Four times he was so out of control, he was hospitalized.

“We’ve had to barricade ourselves in a room at times to protect ourselves. It’s scary. He targets me the most,” because he is more attached to her than anyone else.

Finding help was frustrating. In a blog she wrote: “We searched high and low for professionals who would be able to see past the typical childhood issues and accept that his issues were so deep-rooted that he needed something different, but sadly only encountered ‘professionals’ unwilling to modify their typical methods of intervention and even some who judged us for wanting to even begin to think traditional therapy would not work. In the end, nothing worked. They either wanted to use medication as a means to control him (overmedicating him which ultimately landed him in the hospital with a heart condition) or they wanted to ‘talk him to death’ when he had no interest in hearing them nor was he capable due to severe inability to focus and inability to control his impulses.”

The diagnosis

When Torie didn’t get his way, he ran away into nearby Oak Openings. He climbed to the top of their pole barn and threatened to jump off. He said he didn’t want to be part of the family or their love.

“I love this kid so much but the things he does are so horrific,” Mrs. Haton said.

Two years ago, they enrolled him in Boys Town in Nebraska for nine months of residential treatment, during which Mrs. Haton returned to work to help pay for the tremendous expenses. They spoke with him daily, assuring him they were his forever family. She tucked him in by phone every night, and with an excellent therapist, he learned some self control.

A few weeks ago, he was diagnosed with RAD.

“The first thing I felt was relief. We suspected it. Now we’ll search for more resources,” she said. Among his therapies is horseback riding at Project H.O.P.E., run by therapist Sandra Tebbe in Bowling Green. Children grow attached to the gentle horses, half of whom have been neglected or abused, which the youngsters can relate to, said Ms. Tebbe.

A ‘huge milestone’

Torie’s effect on the Haton’s other children is mixed. Their 16-year-old son is laid back and takes Torie’s behavior in stride. Their daughter, 12, struggled when Torie went to her school (he now attends an alternate-learning center) and resents that he demands so much of their parents’ attention.

“I can imagine in her mind it’s Torie, Torie, Torie. But she’s a lot more mature than Torie. She can handle a lot of chaos. She’s rolled with the flow. She is very strong,” Mrs. Haton said.

Because of the tumult, they have few steadfast friends. Torie’s been combative with his grandparents, who are in their 70s. Mr. Haton changed jobs to be closer to home. Mrs. Haton maintains equilibrium by exercising, praying, participating in an online support group, and thinking about how far he’s come.

“The newest thing — a huge milestone — is he shows remorse and asks for forgiveness,” she said.

“I now understand completely that this journey is not just about the healing of my child and how I can help him, but maybe, just maybe, we as adoptive parents of traumatized children are meant to endure our own misery and hell for a time so that we may better fathom, just a fraction of the hell that our children have endured. I know now that I needed to suffer along with my child to fully comprehend and gain some insight into the pain he endured in my absence,” she wrote.

There are days when she’s so physically exhausted and emotionally drained, “as soon as my husband gets home I sink into bed, and he respects that.” She knows she dances near the edge of depression but refuses to go there.

“I can just accept it for what it is and find every resource for our family and make the best of it. It is getting better. It’s baby steps. We feel like we’re finally climbing up the mountain instead of tumbling down.”

With intensive one-on-one assistance at school, Torie is at grade level. He can sit through a church service. He didn’t run away but held her hand when they all went to an amusement park last summer.

“We feel he’s meant to be with us,” she said, adding that Torie still fears he’ll be “sent back.”

“A lot of people think love will heal,” said Mrs. Haton. “That is absolutely true but there’s so much more that needs to be there.”

Contact Tahree Lane at: tlane@theblade.com or 419-724-6075.