Longtime baseball player switches sides, becomes an umpire

8/17/2014

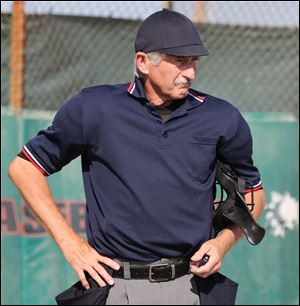

Umpire Tom Walton says he’s learned that the umpire behind the plate in a two-man crew has only two friends on the field. ‘His partner is one. The catcher, whose job it is to stop the ball before part of my body does, is the other.’

THE BLADE/JEREMY WADSWORTH

Buy This Image

Umpire Tom Walton says he’s learned that the umpire behind the plate in a two-man crew has only two friends on the field. ‘His partner is one. The catcher, whose job it is to stop the ball before part of my body does, is the other.’

I turned blue a while back, and I’m happy to report that no choking was involved.

I hung up the baseball uniform I’ve been wearing for one team or another much of my life and became an umpire. For those who look at an umpire and only see red, let me explain that “Blue” is the generic name given to all baseball and softball umpires.

Umpiring is not something I ever aspired to do. I’ve played baseball since childhood. The umpire was a guy with enormous power and authority but also someone nobody seemed to like. I felt a little bad for the abuse the officials took from players, fans, and coaches, but only up to a point.

Brondes catcher Ethan Bennett, 9, makes the catch as Mr. Walton looks on.

However, two teammates on my Roy Hobbs baseball team — local attorney Jim Adray and retired Toledo firefighter Bob Curtis — talked me into going to umpire school with them last year in Florida. That was followed by a much more thorough nine-week course over the winter here in Toledo. Instructors Bob Sobecki and Mark Kuhn have been umpiring locally for a long time, so I tried to absorb as much of their wisdom as I could.

I took the state tests, and what do you know? I passed and became a card-carrying official for the Ohio High School Athletic Association and a member of the Metropolitan Toledo Umpires Association. You could make the case that the OHSAA needs to tighten up its standards, but it’s too late.

I’m in. A 70-year-old rookie.

So now I’m working games from the peewee level to high school. Some of the guys I’ve played with for years at Skeldon Stadium in Maumee say I’ve gone over to the dark side. To the contrary, I see the light. The experience has changed the way I perceive the game.

An umpire quickly gets used to being called “Blue.” I discovered how many youngsters these days have names that sound just like “Blue.” Hey Drew. Hey Stu. Hey Lou. Hey Hugh. Hey Boo. Even Hey You. It was a relief to figure out that I’m not the only guy out there the coaches are yelling at.

As with most sports, the rules of baseball are often about common sense and always about denying an unfair advantage to a player or team.

Here’s a situation. You make the call:

With runners at first and second, and one out, the batter hits a ground ball toward the shortstop. Before the defensive player has a chance to make a play on it, the ball strikes the runner attempting to advance to third.

Ruling: The ball is “dead” immediately. The runner is declared out, the batter is awarded first base, and the runner who was at first moves to second. Now there are runners at first and second and two outs.

One game in particular was memorable because the coach would not let up. “C’mon Blue, get it right!” “Blue, you’ve got to work a little harder.” “Hey Blue, you’re better than that.” Stuff like that. I try to tune out most of the nastiness and chalk it up to passion and competitive energy. Even so, I was getting depressed. “I can’t do anything right according to this guy,” I thought.

Then he shouted “Let’s go Blue. Be a hitter.”

He hadn’t been carping at me after all. His players wore blue uniforms and he was addressing them all as simply “Blue.” Next year, Coach, outfit ’em in purple, huh?

Heckling comes with the territory. I usually tune it out. But I recall a game in which it was impossible not to hear a shrill voice screaming at me from the bleachers: “Hey Ump! A blind man could have made that call!”

I felt like turning to the guilty party and blurting out: “A blind man DID!” It would have broken the tension, but it also would have broken a rule: Never engage the fans during the heat of the moment.

Thomas Walton, 70, umpires a youth baseball game between the Maumee Jr. Panthers and Brondes Ford Lincoln at Carter Park in Bowling Green.

I learned early that the umpire behind the plate in a two-man crew has only two friends on the field. His partner is one. The catcher, whose job it is to stop the ball before part of my body does, is the other. If he’s good at that, we get along fine. If he’s not, I can be quite stern.

It’s a lesson learned early and never forgotten by an umpire: the ball will find you.

Sometimes it’s not the catcher’s fault. I took a direct hit in the face mask from a foul-tip, and while there was no pain, it was a shock to the system when the mask flew halfway to the backstop. Without the mask I would have had the word “Rawlings” imprinted backwards on my forehead for the rest of my life. Had I lived.

“You OK?” a baseball mom in a folding chair asked from behind the fence — an unanticipated and compassionate show of concern rarely encountered between the lines — certainly not something you expect to hear from someone with a blood relative who’s a combatant in the fray.

“Yeah, I’m fine,” I responded. “This is why I get the big bucks.”

The Metropolitan Toledo Umpires Association as well as other umpiring associations in the area have an ongoing need for new umpires.

If umpiring sounds like something you’d like to try, the Toledo group will offer its nine-week course beginning in late January. The class will meet for three hours on Tuesday evenings at Start High School.

The fee is $145, which includes the umpire permit fee for the first year. Information is available through Bob Sobecki, president of the Metropolitan Toledo Umpires Association, at bob_sobecki@mtua.org.

Most of the association’s umpires are men, but women are welcome too. A course is also offered for softball officials.

Getting hit now and then does tend to call attention to the gentleman in blue taking the blow, but the umpire’s goal is to go pretty much unnoticed. An umpire, in other words, should be the guy who could walk into an empty room and blend right in. Like me.

The pay — $45 to $55 a game is fairly standard at the high school level in Toledo — is nice, but it’s not the only reason the umpires I’ve worked with do this. Most of them simply love the game and want to stay involved with it.

Good thing, because becoming an ump can require an investment of a few hundred dollars in protective equipment.

A mask, shin guards, chest protector, and steel-plated shoes are the big-ticket items, but the clothing adds up, too.

Umpires in the Metropolitan Toledo Umpires Association and accredited by the Ohio High School Athletic Association must wear the required uniform: a navy blue shirt with the state association logo, gray pants, and a logo cap. Work enough games and the investment is soon recovered.

What matters a great deal to these guys is their integrity. They pride themselves on being the impartial arbiters of a complex game with myriad rules that require instant recall and application, knowing that whatever they decide, they’re probably going to hear about it from the coach whose team didn’t get the call.

Defining the strike zone is a critical part of an umpire’s job if he’s working behind home plate. The book tells us what it is, but umpires don’t get the benefit of a television replay to show them whether the ball flew over the plate.

I remember calling a strike on a nice pitch on the outside corner. A fan shouted “Hey Blue! He couldn’t have hit that pitch with a 10-foot pole.” I’m thinking to myself, “You’re probably right; he’s not a very good hitter. But it caught the corner and it was still in the strike zone.”

Mr. Walton calls Maumee's Dylan Riley, 9, safe at the plate.

I shared my most embarrassing moment. Here’s one that fortunately went the other way. A coach ran out to my position to argue that we had misapplied the infield fly rule. After I patiently and I think politely explained the rule, he marched off to the dugout, promising to return with the baseball rule book.

A bit later, he walked up to me between innings and said simply: “You were right. The rule is clear. I don’t know what I was thinking.”

It was a classy thing to do and much appreciated.

That’s not to say the guys in blue are perfect. Contrary to the belief of some, umpires are human. Humans err. The best coaches know the nuances of the rules too and they’re not shy about sharing their knowledge.

Sportsmanship and character-building are an important part of the game, and most of the players understand that and play hard but fair.

Sometimes, however, the adults make it difficult. I actually heard one mother shout at her son, “If he’s in your way next time, just bowl him over.” Not cool.

It’s great to be out there on a field of dreams at my age. I still wear a uniform. I still smell the grass. I still hear the crack of the bat. I still play in the dirt. But two things have changed: I’m a rookie again, and I no longer care who wins.

I haven’t decided if I’ll go back to playing senior baseball, but my body is telling me I won’t be able to keep at it much longer. Fortunately, turning blue has made the transition a whole lot easier.

Tom Walton is the retired editor and vice president of The Blade. His column appears every other Monday on the Pages of Opinion. His radio feature, “Life As We Know It,” can be heard every Monday at 5:44 p.m. during “All Things Considered” on WGTE FM 91. Contact him at: twalton@theblade.com