TOLEDO MAGAZINE

Natural Allies: Humans, trees have a metaphysical relationship

8/24/2014

The fascinating world of plants and trees is all around us, but we scarcely comprehend its influence on our lives.

Trees and their roots work in a slow-motion symphony to amuse, entertain, and sustain us. While the trees look skyward in pursuit of sunlight, their roots spread deeper in the ground to tap moisture and nutrients from Mother Earth. As the tiny sapling grows into a majestic and towering tree, its roots, hidden from our view, also grow and match the majesty of the visible parts.

Like humans, trees are susceptible to the forces of nature. When devastating storms and hurricane-force winds spread their misery, trees get uprooted and toppled. The branches of some of the fallen trees, in an expression of Darwinian survival of the fittest, reach down to the ground and make new connection with the earth. Roles change and the branches become roots to sustain the mother tree. Most fallen trees whither and die, but some refuse to succumb.

DIGITAL DOWNLOAD: Get a PDF of today‘s Toledo Magazine

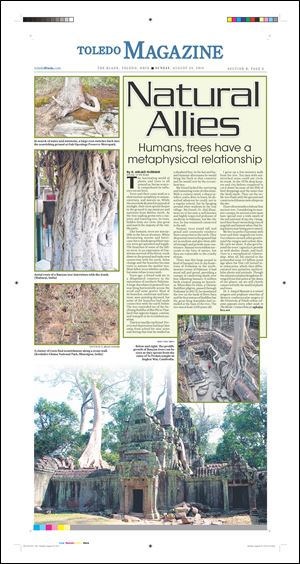

Years ago, a friend took me to a dilapidated cemetery in the mountains of northern Pakistan. A large sheesham (rosewood) tree was lying horizontally across the scrub and some graves. Most of its branches, exuberant and luxuriant, were pointing skyward, but some of the branches had made connection with the earth below. The tree reminded me of the Reclining Buddha of Wat Phi in Thailand that appears happy, content, and tranquil in recumbent position.

That tree was like my friend. Poverty and deprivation had kept him away from school for nine years and during that time he worked as a shepherd boy. In the hot and humid summer afternoons he would bring his flock to that cemetery and he would rest by the recumbent tree.

My friend lacked the nurturing and sustaining roots of education. With a curious mind, a sharp intellect, and a drive to learn, he absorbed whatever he could, not in a regular school, but by hanging around other students in the tiny village. My friend, Dr. Alaf Khan, went on to become a well-known and highly respected professor of medicine in Pakistan, but like the tree, he has remained connected to the soil.

Banyan trees stand tall and proud and constantly reinforce their connection to the earth. They drop aerial roots to the ground that act as anchors and give them added strength and provide more sustenance. Banyan trees seldom succumb to the fury of nature, but they are vulnerable to the cruelty of man.

There was this large peepal (a kind of banyan) tree in my hometown of Peshawar in the northwestern corner of Pakistan. It had stood tall and proud, providing a canopy of comforting shade over four adjoining bazaars. A million birds roosted among its branches. When Shin Fa-Hian, a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, passed through Peshawar in 400 CE, he mentioned the tree on the bank of River Bara and the four statues of Buddha that the great King Kanishka had installed at the base of the tree. The tree was at least 2,000 years old.

I grew up a few minutes walk from the tree. Ten men with out-stretched arms could not circle its trunk. In the 1970s shop keepers and city fathers conspired to cut it down because of the filth of bird droppings and the noise that the birds made. They cut the noble tree flush with the ground and constructed dozens more shops on the site.

I have often wondered about that ancient tree. Considering its massive canopy, its ancient roots must have spread over a wide swath of the soil and soul of my city. I imagined their heart-wrenching cries of anguish and lament when that living history was being put to sword.

We live in perfect harmony with trees and their magnificent roots. Our reliance on each other goes beyond the oxygen and carbon dioxide cycle we share. It also goes beyond the trees’ capacity to provide us with shelter, shade, and food. Ours is a metaphysical relationship. After all, life started in the primordial soup 4.6 billion years ago when the first cell turned into eukaryotes, which then differentiated into primitive multicellular plants and animals. Though the animal and plant kingdoms diverged from that point at the dawn of our planet, we are still closely connected with the world of plants and trees.

Dr. S. Amjad Hussain is a retired surgeon and professor emeritus of thoracic cardiovascular surgery at the University of Toledo whose column appears every other week in The Blade. Contact him at: aghaji@bex.net.