COMMENTARY

When does political ‘principle’ become mere stubbornness?

10/20/2013

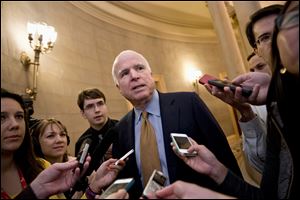

Sen. John McCain (R., Ariz.) talks to reporters on Capitol Hill last week upon his return from a two-hour meeting at the White House between President Obama and Republican senators.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

David M. Shribman.

The drama of the past two weeks has been about the future of nationally mandated health insurance, resuming government spending, extending the debt ceiling, and avoiding national default.

These are all important matters — any one of them could be enough to stop a country dead in its tracks. The ordeal of October, 2013, surely will be studied by scholars for years to come.

But in a way, this month’s crisis has been about even greater issues, not the sort that are debated on the floor of the House or Senate or even in political science classes. Instead, they are the preoccupation of the philosophy department and the pulpit.

We have been so consumed with avoiding default, or charting the barometric pressure inside the House Republican conference, or watching House Speaker John Boehner of Ohio balance what he wanted to do with what he needed to do, that we have overlooked the more enduring questions this episode has posed.

Sen. John McCain (R., Ariz.) talks to reporters on Capitol Hill last week upon his return from a two-hour meeting at the White House between President Obama and Republican senators.

We knew from the start of this struggle that eventually the government would open and that eventually Washington would pay its bills. We know that this crisis has raised but not answered these questions, unavoidable in our private lives even if they are avoidable in lawmakers’ public lives:

● When does principled resistance become stubbornness and intransigence?

House Republicans angered Democrats and some Republicans because of their determination not to allow the regular functions of government to proceed until Obamacare was repealed, trimmed back, or adjusted.

Many of these lawmakers were elected from conservative districts where resistance to Obamacare is genuine and strong, and where their election to Congress was fueled by their vows to fight Obamacare on the beaches, on the landing grounds, in the fields, in the streets, and in the hills.

Many of you will recognize that the latter was paraphrased from Winston Churchill’s June, 1940, “we shall never surrender” speech, which is saluted (as Mr. Churchill would say) by English-speaking people as the ultimate expression of political and moral determination. We celebrate it because we admire the cause in which he enlisted those brave words: the defeat of a brutal tyranny bent on world domination and the extermination of its enemies, both military and civilian.

Only a very few would create a moral equivalency between the drive to defeat Hitler and the drive to defeat Obamacare. There is a legitimate case to be made for proportion and for distinctions made on ethical grounds, for there is a grave difference between government-mandated insurance and government-sponsored genocide.

But in questions of acknowledged lesser consequence, it is not as easy as the Tea Party critics say it is to draw the line between resistance and intransigence.

● When does the practical trump the principle?

From the start, Sen. John McCain of Arizona told his GOP colleagues that their one-house challenge to Obamacare was quixotic but doomed. “We were demanding something that was not achievable,” he said in exasperation last week as he declared the GOP had “lost this battle.”

His words had greater force after a fortnight of struggle than they did at the beginning of the capital confrontation. And yet many of the House rebels believed fervently that they had to undertake this battle, that to bow to the practical was to sacrifice the principle.

● When does standing for one principle violate other principles?

From the Republican viewpoint, the showdown that gripped the Capitol pitted one widely held principle (antagonism toward Obamacare) against another one (financial responsibility).

In cases such as this, lawmakers have to weigh not only the moral value of one against the other, but also the practical consequences of one against the other.

In the minds of mainstream Republicans, the Tea Partiers made the wrong choice. But in the minds of the rebels, they made the right choice, calculating that the sense of financial responsibility of their rivals would make them fold.

These rebels weren’t the only ones playing that game. Democrats made the same calculation, convincing themselves that the party of business would bend to business values, allowing them to keep Obamacare free from fetters. Of such calculations are crises made.

● When do we prize steely determination and when do we condemn it?

That sounds like a hard one, but it’s really easy, which is why the country faced such a threat this month. We prize steely determination when we like a cause (integration is a good example) and we condemn it when we revile a cause (segregation, for instance).

● When does a leader’s responsibility rest with expressing the will of his followers, and when does it rest with serving a greater good? And does a leader have the right, or responsibility, to discern a greater good?

Welcome to Mr. Boehner’s world — and to the prison of his position. From the beginning, he knew what his conservative wing wanted, and he knew that financial default was a political, financial, and moral disaster.

If he did not know it at the beginning, he surely knew a week into the struggle that there was little likelihood of reconciling what some of his supporters wanted with what the nation needed.

Mr. Boehner knew that his was a conundrum for the ages, a choice, like so much else in this episode, between competing perspectives — and a test case in one of the hardest decisions in life, and in politics: when to fight on principle and when to quit in principle.

David Shribman is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact him at: dshribman@post-gazette.com