COMMENTARY

The long year of 2013, full of great unresolveds

This year’s budget negotiations underlined the tensions in our politics and the limits of our political system

12/22/2013

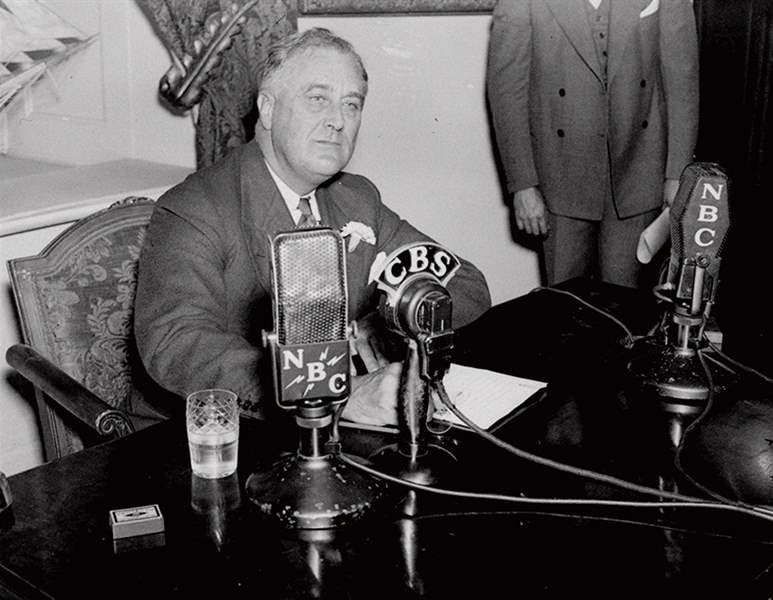

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering one of his fireside chats. He contended that the country faced a crisis that required a practical response.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

David M. Shribman

We live with artificial boundaries in space and time. The Danube River pays no mind to borders; it runs through 10 countries. The Amazon runs through six, and the Nile through five.

The 20th century arguably didn’t begin until 1914 and plausibly can be thought of having ended in 1989.

Which is why it’s possible to argue that 2013 won’t end nine days from now. It’s almost certainly going to extend into January and beyond.

This is no parlor trick, though it bears a strong resemblance to a parlor game. But if you stretch the definition of a year from a line of 365 days (or, every four years, 366) into an arc of events, then you will see that the tributaries of politics and the rivers of history do not confine themselves to the neat contrivances of the calendar, nor to the enduring rhythms of the Earth’s passage around the sun.

The year 2013 wasn’t so great that any of us is eager to extend it, but the struggles set in motion this year will not be resolved by New Year’s Eve. The questions prompted throughout this year will not be answered by the time the Duke-Texas A&M game in Atlanta’s Georgia Dome is completed that night. They’ll press on, through the national college football championship game a week later — and beyond.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering one of his fireside chats. He contended that the country faced a crisis that required a practical response.

There are two predominant reasons. This is the first year of a two-year Congress; many of the pieces of legislation begun this year will, as a matter of course that has happened 112 times in the past, slop over to the new year. This is thoroughly unremarkable.

So too is the notion that larger movements in politics — the slide to the right by Republicans and to the left by Democrats, for example, and the tug of war between those who want to expand government and those who want to constrain it — do not respect the changing of the calendar. They are the mainstreams of history and they flow on.

This year’s budget negotiations and the series of short-term agreements underlined both the tensions in our current politics and the limits of our political system.

On the surface, these discussions were about this program and that, about this tax and that entitlement, and about the level of military spending. These issues come and go — though the tax and entitlement questions will come and go with increasing frequency as the decade wears on and demographic factors bear down.

But they are proxies for a far bigger issue. They are part of a classic confrontation between those who have an expansive view of the virtue and value of state spending and those who believe a vigorous, activist state is an intrusion on the natural order and a departure from our national character.

We have had these debates before. This conversation raged near the start of the last century, and the Progressives won.

It raged after the onset of the Great Depression, and the New Dealers won. It raged after the end of the Dwight Eisenhower years and the New Frontier. Great Society visionaries and dreamers won. It raged again during the Jimmy Carter administration, and the Reaganites won.

Acolytes of Ronald Reagan held sway for about a generation. In another example of how events conspire to defy the usual borders, it is quite possible to argue that Reaganite views controlled Washington, as early as the Carter White House. These views seeped into the Bill Clinton years and prevailed through the first six years of the George W. Bush administration.

Then the Reagan impulse petered out. It remained part of the catechism of conservatism, of course, but was unrequited.

The last years of the Bush 43 administration bore a great resemblance, if not precisely in the level of spending and in the size of the deficit, then surely in the philosophy of governance, to the early years of the Obama Administration. Members of the Bush and Obama administrations will deny this emphatically, but a quarter century from now, you will see that historians will agree with me and not with them.

There are other great unresolveds. One is the definition of our parties, both philosophically and geographically. The Democratic Solid South has been replaced by a Republican version.

The parties no longer have conservative and liberal wings. We now have a liberal party and a conservative party. The question remains whether a system so constituted — but surely not so designed — can long endure.

Another of the great unresolveds is whether health care is a national right to be enforced by Washington, much the way free access to the ballot box and equal protection of the laws are now beyond debate.

One side believes fervently that it is, and that the march of history will lead us to a national concurrence, the way Medicare went from controversial to consensual.

The other believes just as fervently that Obamacare is a dangerous departure from the American system, a restriction of freedom at odds with our history.

These two vantage points seem incompatible. But then again, so did the two titanic forces — President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s insistence that the New Deal was an inevitable extension of historical forces and the conservative argument that it threatened the American character — that went to battle during the Great Depression.

As early as May 7, 1933, well before the end of his first 100 days, FDR was arguing that the country was facing a crisis that required a practical rather than a philosophical response.

“That situation in that crisis did not call for any complicated consideration of economic panaceas or fancy plans,” he said in his second fireside chat. “We were faced by a condition and not a theory.”

The greatest unresolved of them all: Is our situation at the end of 2013 the result of a condition or a theory? On that rests everything else.

David Shribman is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact him at: dshribman@post-gazette.com