COMMENTARY

Toledo is losing the race for tomorrow’s good jobs

Nearly four out of five young workers in Toledo lack college degrees, and that rate isn’t improving

2/16/2014

Dave Kushma

Dave Kushma

Ohioans will hear a load of happy talk from political candidates this election year about how the state’s economy is rebounding, and how jobs are coming back and getting better. But workers in Ohio’s hardest-pressed communities — notably Toledo — live a different reality.

A new study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland concludes that the job and earnings prospects of workers who aren’t college graduates depend on their occupations, the kind of training they get — and where they live. That isn’t good news for Glass City.

Nearly two-thirds of American workers from ages 18 through 35 don’t have a four-year college degree. But in metropolitan Toledo, that share is almost four-fifths, and it isn’t getting better.

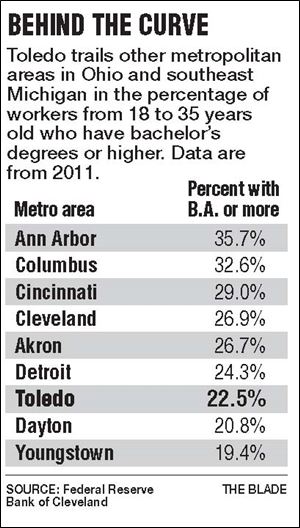

Among the nation’s 100 largest metro areas, the Cleveland Fed study finds, Toledo ranks a dismal 72nd in the educational attainment of its young workers — better than Dayton and Youngstown, but well below Ann Arbor, Columbus, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Akron, and Detroit.

The better news is that the percentage of young workers in the Toledo region who dropped out of high school is relatively low — about 6 percent. Still, one out of six workers in the Toledo area with a high-school degree, but no more, is unemployed.

“Toledo really has to pay attention to this now,” says Francisca Richter, a research economist in the Cleveland Fed’s community development office and a coauthor of the study. “The education level of the work force is something to worry about.”

It’s no secret that better-educated workers generally earn more than less-educated ones. That gap has widened since the early 1980s, as the American labor market has increasingly divided into high-skill/high-wage jobs and low-skill/low-wage ones.

The Fed study finds that this wage premium varies among metro areas. In Cincinnati, the typical worker with at least a bachelor’s degree makes 84 percent more than the typical worker with a high school diploma. In Toledo, it’s 71 percent.

Training counts

At the same time, a college degree is no guarantee of higher pay. The Fed report observes that some employees with high-school degrees can command better wages than many college graduates, if they work in occupations that reward advanced technical training through apprenticeships and certification programs.

The apprenticeship and training center in Rossford run by Local 8 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, and supported by area contractors, trains its graduates to acquire work skills in such leading-edge industries as alternative energy. The union program is a heartening success story, but it needs much broader local emulation.

Many manufacturing jobs continue to pay decent wages to workers with high-school educations. But in Ohio, the report notes, the number of manufacturing jobs has dropped since 2006. As we continue to shift to a service economy, many manufacturing jobs won’t ever return.

Even more troublesome for Toledo is the study’s identification of the “knowledge spillover” effect: In communities with larger percentages of college graduates, workers with high-school diplomas also tend to earn more. That’s because education is a collective as well as an individual good.

Employers in better-educated communities, the Fed study finds, are in a better position to embrace innovations that make workers more productive. That reality places Toledo at a competitive disadvantage to every other Ohio metro area in the study except Youngstown. “Toledo does not have that knowledge base,” Ms. Richter told me.

A related Cleveland Fed study released this month examines the mismatch between job skills and opportunities in Ohio. Despite Ohio’s still-high unemployment rate, many employers in Toledo and across the state report a shortage of candidates with the necessary skills to fill their job vacancies.

Even so, job seekers often complain they can’t find out about training opportunities and career paths. The Fed concludes that “data related to agencies, employers, and job seekers [are] neither standardized, coordinated, nor adequately disseminated.”

Says Lisa Nelson, a senior policy analyst with the Cleveland Fed’s community development team who coauthored the jobs study with Ms. Richter: “Kids need to be aware that this is not old manufacturing. The new jobs require the right technical skills and soft skills. We need to connect them better with employers.”

What to do

How can Toledo and Ohio address these problems and create more and better jobs? It’s no mystery: We need to invest more in basic education, from preschool to high school. Area school districts need to concentrate even more on boosting their high school graduation rates. Toledo and Lucas County must finally get their act together on improving the local Head Start preschool program.

We need to do a better job of aligning higher-education opportunities with the demands of northwest Ohio’s labor market — although that does not mean turning Toledo area universities and colleges into trade schools. We need to pay greater attention to workers who don’t want to attend a four-year college but still seek more education and training.

Ohio also needs to invest more in work-force development, but it isn’t just a matter of money. If state government could standardize the data kept by various agencies involved with job training, and work with Ohio employers, educators, and workers to define a set of common objectives for training, such things would save rather than cost taxpayers money.

Achieving these goals is easier said than done. It will force politicians to invest in children who don’t vote, and young people who are often turned off from voting, rather than give still more tax cuts to the richest Ohioans, who vote in disproportionate numbers. It will force school districts to focus on the needs of their students ahead of the demands of interest-group constituencies.

And it will force voters to keep their eye on the ball, instead of getting diverted by such phony controversies as whether the national Common Core curriculum is a socialist conspiracy to destroy local schools. It isn’t.

Toledo doesn’t have to settle for staying in the back of the pack. The Fed researchers note that Pittsburgh, whose fortunes once rose and fell with the steel industry, has reinvented itself as a “brain hub.” Our community has the resources to do the same thing, once we start pulling together toward that end.

“It takes many years to shape a labor force, but it’s never too early to start,” Ms. Richter says. “I would not give up on our kids — there’s a lot of potential.”

David Kushma is editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: dkushma@theblade.com or on Twitter @dkushma1