Second in a three-part series

Quest to achieve

TPS officials pursue several strategies in effort to elevate student performance

5/9/2011

Teacher Donna Garth waits for an answer from Jazzlyn Whitlow, 9, right, during a ‘Jeopardy’-like math game in her third-grade classroom at Pickett Academy. Pickett is Toledo’s most chronically poor performing school, but a closer look at the data shows students at the central-city school are making progress.

Donna Garth is invisible.

Though she sits right next to seven third graders crowded in a circle in her Pickett Academy classroom, they aren’t supposed to see her or look to her for answers. This is their lesson to teach.

A young girl with thinly twisted dreadlocks reads aloud a paragraph about George Washington Carver’s early years, then turns to a boy seated next to her and quietly asks him a question.

Ms. Garth, with freckles dotting her face, looks over her glasses at the girl and briefly suspends her invisibility, urging the girl to talk a little louder.

“Why did Carver have to leave to go to school?” the girl asks again.

“Because where he lived at,” the boy responds, “black people weren’t allowed to go to school.”

Pickett is Toledo’s most chronically poor performing school. The central Toledo building, temporarily on Lawrence Avenue a block off Dorr Street, has been on the school-improvement list under the No Child Left Behind Act for 11 years, four more than any other school in the district.

In 2008, after years of failing test scores, officials at Toledo Public Schools remade Pickett, replacing most of its teachers and leadership, hoping to turn the school around.

More than half of the schools’ teachers were replaced by either new hires such as Ms. Garth, who had been a long-term substitute, or teachers from other schools. A new principal and Assistant Principal Martha Jude were put in place. Ms. Jude is now the principal.

The school has remained on the school improvement list, but a closer look at the data shows students at Pickett are learning.

Since 2008, Pickett’s performance index — a weighted average of test scores — has risen from a 61 to a 65, a jump that shows growth in about 100 of the school’s 360 students, said Romules Durant, assistant superintendent for elementary education.

That score is still low. In fact, the school was rated last year in academic emergency, equivalent to an F grade.

But Pickett’s value-added scores in both fourth and fifth grade showed above-average growth in both reading and math. And though state reports don’t show it, Ms. Garth said her class also made more than a year’s growth.

Yet Pickett’s improvements in many ways show how deep a hole it was in and how hard it will be to dig out.

Ms. Garth put it this way: If a student comes into her third-grade class at a first-grade reading level, even her best efforts probably will get that student only to a second-grade reading level by the end of the year.

“Let’s just be realistic,” she said.

That’s a year’s worth of growth, and by most metrics, a success.

Which is why Pickett still scores so low. Despite student improvement at Pickett, in no grade or subject did more than 47 percent of Pickett students score proficient last year.

“You can’t just jump out of the hole,” Ms. Jude said.

But there’s a hope, in fact an expectation, that students at Pickett and four other central-city schools will make major jumps in the reading scores of third-grade classes such as Ms. Garth’s.

Raising performance

Eleven sets of eyes locked onto Molly Henry, readying the mouths below to fill a Spring Elementary third-grade classroom with a chorus.

“Echo read please!” Ms. Henry shouted to her class. “Ice, rice, mice,” the students called back after her prompts.

Later, students separated syllables on folded pieces of paper, then listed words that are on a white board under the syllables. They are learning how to mentally group words by similar sounds. These skills should have been learned in second grade.

“Our kids have such a deficit in what they come to school with,” Ms. Henry said.

They’re getting it now.

Split off on a table near a bank of windows, five students worked on similar lessons with Brenda Hutmacher, the homeroom teacher. Those students are ahead of their classmates and work on advanced lessons while their classmates try to catch up.

Exercises such as these stretch through much of the morning.

Diane Pickering, an intervention assessment teacher, oversees a group of students at Spring Elementary School. Third grader Antonia Lopez, 10, next to Ms. Pickering, was ‘leading’ the group, which included Daniel Combs, 10, left, Russell Bland, 8, and Terrell Newble, 8. The lesson is part of the Reading Academy Intensive Support Education program that aims to boost reading scores.

The Toledo Public School system has instituted an intensive reading program as part of the Obama Administration’s Race to the Top initiative. The federal program aimed at reforming schools is pumping $10.8 million into the Toledo district.

Many of the reform elements for Ohio’s Race to the Top program are in development, but Toledo already is using a reading initiative, called RAISE — Reading Academy Intensive Support Education —to try to boost reading scores in third grade.

At its core, RAISE is simply an intensive reading program using well-tested techniques. Teachers, for two hours a day, focus entirely on students’ literacy skills.

One of the main concepts used, and one lauded by teachers, is a process called reciprocal teaching, in which students and teachers analyze stories together.

Students read a short story to themselves, then break the stories up into paragraphs. Students must predict what will happen in each paragraph, ask questions, and summarize what they read, while focusing on difficult words.

They do this aloud, and the concept works best in small groups. To do that in classrooms that sometimes have nearly 30 children, building reading coaches — such as Ms. Garth — and interventionists augment the classroom teacher, breaking classrooms up.

Then comes the part Ms. Garth loves the most. Students take control of the lessons, leading their peers through the questions and summaries. That’s why Ms. Garth was invisible to her Pickett students.

“I like the way they take ownership of it,” she said. “They are participants in their own learning.”

The district didn’t have to look outside Toledo for the RAISE program. It was developed in-house, and teachers in the district’s Reading Academy taught their peers the concepts.

Teachers brought RAISE to the classrooms in February, and nearly everyone involved with it expects immediate, and significant, returns. Why?

“We see this,” Ms. Henry said, pointing to her students.

High expectations

Internal data are driving those expectations. Mr. Durant, the assistant superintendent, said his data project that Martin Luther King will have major gains in third-grade reading scores, “guaranteed.” The other four schools all show internal scores that project major gains as well, with Rosa Parks leading the pack.

“I am expecting to see huge growth in their scores,” Mr. Durant said.

The district turned to RAISE because educators knew it would work. It already had.

Toledo developed the program last decade because of Ohio’s fourth-grade guarantee rule for reading scores, which ordered districts to hold students in the grade if they failed state standardized reading tests. The district used it as a summer school intervention program.

Half of all students who participated passed the reading assessment, and 75 percent increased at least a level, said Jim Gault, Toledo’s interim chief academic officer.

The program ended when state funding stopped.

“Instead of looking to bring that back into the regular school day, funding dried up, so we cut it,” he said. “We probably started some new initiative … and then we cut that.”

READ MORE: Test results help detect, address shortcomings.

On the move

The fifth time was the charm for Denzel Moore.

After years of family turmoil that led to constant moves between homes and four different elementary schools, he found the semblance of stability at Riverside Elementary in North Toledo.

He stayed at Riverside for three years, the longest stint at one school in his life.

Denzel and his mother said they had a different feeling about Riverside than at other schools. It seemed teachers took more time with Denzel there.

Denzel’s grades started to improve.

But then change came again. Denzel moved on to middle school, and after a three-month stint at Leverette, he moved on to Samuel M. Jones at Gunckel Park Middle School.

Along with the appearance of Denzel’s teenage angst, and girls, his mother adds, came another, more dangerous addition to those years — violence.

Fights would break out frequently at the school, often not involving students, but kids from the neighborhood. Gangs were a major presence in the school.

Gang members would come to the building and “go off.”

“Just walk up in there and start fighting,” Denzel , now 19 and a student at Scott High, said of gang bangers.

Riots was the word he used. There were riots in his school.

Middle schools

Toledo Public Schools can’t control most student movement. But one massive, annual migration of Toledo students will soon be a thing of the past. Middle schools are no more.

In the element of Toledo’s transformation plan with the most public support, middle schools will be closed and reopened next year as K-8 schools. Elementary schools will be expanded to the eighth grade throughout the district.

Supporters of K-8 schools tout the benefits of eliminating the transition to middle schools at an age when students are experiencing physical and emotional turmoil.

There’s evidence that students at K-8 schools also academically outperform their middle school peers .

An analysis of New York City schools published in the fall edition of Education Next followed students in grades three through eight during the 1998–99 through 2007–08 school years.

The article, “Stuck in the Middle,” by Jonah Rockoff and Benjamin Lockwood of the Columbia University graduate school of business, showed sharp performance declines once students reached middle schools.

“What determines a student’s level of academic achievement is complex,” the authors wrote. “But the simple fact is that students who enter public middle schools in New York City fall behind their peers in K–8 schools.”

The K-8 model dominated the middle school grades a century ago. Junior highs then rose to fashion, only to be supplanted by middle schools.

Now, K-8’s are back in style.

Major metropolitan school districts such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Denver have moved to the K-8 model, as have Cleveland and Cincinnati.

“It’s just not a Toledo thing,” Mr. Durant said. “We didn’t just jump into it.”

But the district isn’t just blindly following a trend. The local numbers, at least on their face, support eliminating Toledo’s public middle schools.

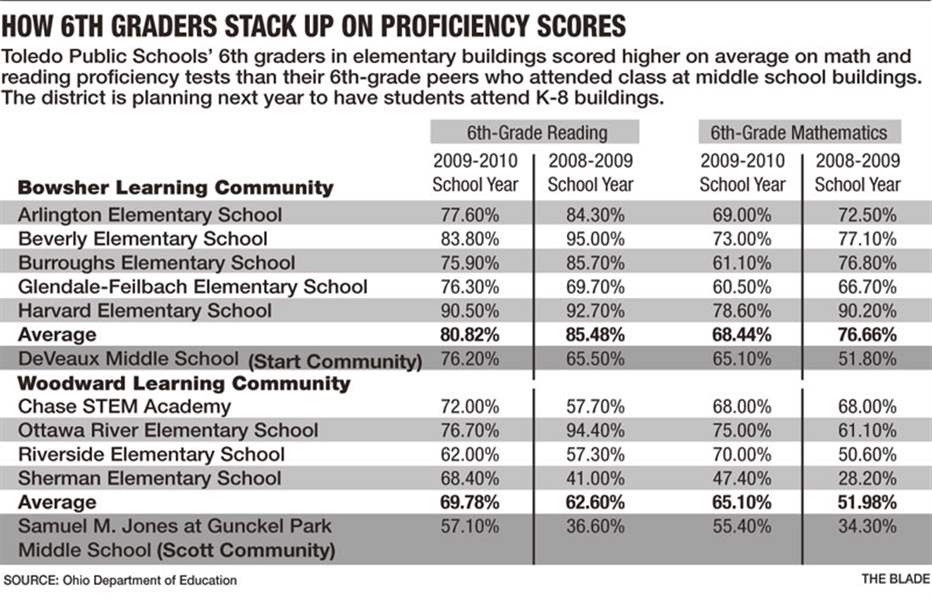

As a whole, Mr. Durant said, sixth graders at Toledo’s elementary schools significantly outperformed their middle school peers.

Some of that, however, can be attributed to social variables independent of education. Mr. Durant said he also analyzed schools with similar characteristics, to try to eliminate those factors.

In the Start-Bowsher comparison, elementary students bested their peers in reading and math by respective averages of 15 and 19 percent in the past two years, when comparative data were available.

The disparity in the Scott-Woodward comparison is even greater. Sixth graders at Woodward elementary schools outperformed those at Jones Middle School by an average of about 27 percent over the past three years, according to data provided by the Ohio Department of Education.

“That just tells you there’s something within that correlation,” Mr. Durant said.

Even when eliminating outliers in economic status, the trend holds true.

The numbers are encouraging for K-8 in Toledo. But a look at one urban school district’s shift to K-8 schools may show the move isn’t a panacea for poor results at middle school grades.

A 2007 study published in the American Journal of Education that analyzed the Philadelphia school system questioned how much of the success of K-8 schools compared to middle schools in the district was from configuration and not external factors.

Written by John Hopkins University researchers Vaughn Byrnes and Allen Ruby, the study examined the performance of 40,000 students over five years, comparing the test scores of students in old K-8 schools, middle schools, and schools recently converted to K-8.

Students at schools that have been historically K-8 schools performed significantly better than their middle school peers; those at newly formed K-8 schools also exceeded the middle school students.

But after controlling for demographics, student mobility, and grade size, Mr. Byrnes and Mr. Ruby found no “discernible difference” between the academic performance of middle schools and K-8 schools, especially those newly formed.

“A district is not likely to replicate the K-8 advantage based upon size and school transition alone if its student population remains unchanged,” the authors wrote.

Remaking Scott

Every year, it seems, something changes at Scott High School.

A new reform is tried, and ultimately abandoned. The school is moved while its building is renovated. A crop of experienced teachers retires.

“There is always upheaval at Scott,” school director Treva Jeffries said.

In 2004, Scott moved to a small-school format, with four autonomous programs housed in the building, after receiving a grant of nearly $1 million in Gates Foundation money. The goal was to forge stronger relationships between students and teachers.

The format was credited with increasing student attendance and graduation rates. But there were also concerns about its cost and effectiveness on student academic achievement.

Two small schools were eventually cut. Then, Scott was moved temporarily to the DeVilbiss building during renovations. This year, students from rival Libbey were transitioned into Scott.

Now, the remaining two small schools — which suffered poor ratings on state report cards — are being scrapped, and Scott is being remade again with a traditional format.

Beyond their academic struggles, the small-school format also had side effects, according to students and staff.

The splitting of the student body fractured the school, with students feeling an allegiance not to Scott, but to their individual program. School spirit dipped.

The reform also wasn’t explained sufficiently to the Scott community, Ms. Jeffries said, leaving parents, alumni, and neighbors feeling estranged from the school.

Now, Ms. Jeffries, an avid Scott booster and a graduate of the high school, is trying to rebuild Scott pride. She expanded the school uniform — students can wear T shirts, but only if they are Scott High School ones.

Denzel Moore praised Ms. Jeffries for the energy she brings to the school.

“She’s trying to turn it around,” he said.

Parental involvement

Patricia Hitt had too much love for an empty home.

She already had raised five children of her own. Divorced and living on her own after her youngest son died at 28 of a pulmonary embolism, she found herself with an empty nest.

So the devoutly religious woman started fostering children — 21 of them.

There were rocky moments. Ms. Hitt had to kick out one girl when the teen brought over gang members to her house. But most of the children simply wanted love, and they got it in the Hitt house.

She didn’t like it when they left. So, she stopped letting them.

The last six children Ms. Hitt has fostered, she’s adopted. Fred Hitt, a junior at Scott High School, was one of them.

Ms. Hitt has had to be hard on her kids, she said, because there was no man in the house. They weren’t allowed to go onto Fulton Street, nor stay out late at night.

“I never let my kids hang in the streets,” she said.

And she made sure they were loved.

Students arrive for a school day at Pickett Academy under the watchful eye of Principal Martha Jude. In 2008, after years of failing test scores, officials in the Toledo Public Schools system remade Pickett, replacing most of its teachers and leadership, hoping to turn the school around.

School choice isn’t always practical for families. Ms. Hitt wanted to send her children to Catholic schools. She doesn’t have the love for Scott High School that her son Fred does.

EdChoice vouchers cover only part of the tuition for high school. Ms. Hitt probably could have covered for one of her children, but not three or four at the same time.

“I didn’t want to split up my boys,” she said.

Downsides of choice

One of the core beliefs inside the district’s transformation plan is, in a way, built on a converse approach to public education as used in much of the school-reform movement.

With many urban public school districts across the country failing, reformers looked to choice, hoping to pull children out of their distressed communities and into better environments.

Choice would bring competition, breaking the monopoly of public education. The competition would force public schools to improve and innovate or slowly bleed off.

But many charter schools aren’t working any better than public schools, at least not in Toledo. Out of more than 30 charter schools, only one was rated excellent last year, while nine were in academic emergency. The added choices often exacerbatemobility problems at urban schools.

“The more choice you give these families, the more it hurts,” said Ms. Henry, the Spring Elementary literacy coach.

While some school districts, such as New York City, closed down dozens of schools and reopened them as charters or magnet schools, Toledo is building a system of neighborhood schools.

School officials hope the approach will, at least in part, build community.

That belief is based on two expectations. First, that keeping students in the same neighborhood schools for nine years will develop continuity for students, along with relationships among students, parents, and teachers.

And second is the plan to expand on partnerships with community groups and service providers, housing their programs inside schools. By putting programs such as the YMCA and Boys and Girls Club inside schools, district officials expect schools to become community hubs, places where everyone knows where to go for community events.

The underlying idea is that keeping students in their communities — strengthening those neighborhoods from within — will be more effective and save more students than pouring kids into an education marketplace. Schools should be the bedrock of a community, not an escape from it.

The hope is that by building stability in schools, the stability will spread to the neighborhoods.

“Relationship is crucial anytime you are talking about eduction,” Mr. Durant said. “You are hoping that relationship is what keeps people.”

They hope.

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com or 419-724-6086.