COMMENTARY

Why we still need Black History Month

Cultural critics, sociologists, journalists, and educators continue to marginalize black achievement

2/9/2014

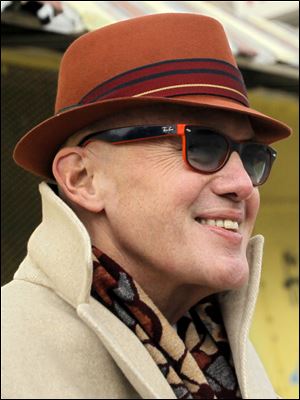

Jeff Gerritt

The Blade

Buy This Image

Jeff Gerritt

Officially recognized by the U.S. government in 1976, Black History Month reboots a debate over whether the nation still needs a designated time to honor the contributions of African-Americans to U.S. culture and history.

Some critics, including African-Americans such as actor Morgan Freeman, argue that black history is American history and shouldn’t be relegated to one month. Others who consider the annual observance unnecessary cite the progress African-Americans have made toward equality over the past 60 years.

Even on that basis, however, the critics are wrong. Moves toward equality, although impressive, have been terribly uneven. The nation has its first African-American president, but it also has nearly 1 million black men in prison — more than were enslaved in the antebellum South — and millions more in poverty.

The Pages of Opinion invite Blade readers to help narrate the importance of Black History Month through the prism of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, “I Have a Dream” speech. But instead of his dream, it will be ours.

We are looking for essays, photos, videos, songs, and drawings about what the month means to you, and how we can use our individual strength to empower all people. We encourage schools to take this on as a project, but we also hope to hear from adults who have dreams for their coworkers, neighbors, friends, and community.

A photo or video could range from diversity exploration in everyday life to participation in a Black History Month program. The Blade will publish some of the contributions, in print and online. Email your offerings to wehaveadream@theblade.com. Please include your name, home address, and daytime telephone number.

That said, I don’t want to make the debate over social, political, and economic progress — important as it is — the central question here. The African-American experience is far more than the failures of this country to live up to its creeds and Constitution.

Even today, cultural critics, sociologists, journalists, and educators — whether in the classroom or on the nightly news — continue to frame the African-American experience largely in terms of pathology and deprivation. That marginalizes black achievement while advancing a legitimate debate over how far the nation needs to go to fulfill the dream of racial equality.

In his 1970 book The Omni Americans, African-American critic and novelist Albert Murray argued that black people couldn’t afford to be reduced to oppression and repression, even though he was vividly aware of their social, economic, and political plight and the need to change it. More than 40 years later, most Americans — especially white Americans — still don’t understand or appreciate the positive contributions of African-Americans, or how much their cultural achievements, struggles, fortitude, history, and even style have shaped the national narrative.

Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, and for that matter, saxophonist John Coltrane and singer Billie Holiday are as important to this nation’s identity as the Founding Fathers, maybe more so. So too are the impressive array of African-American writers — Amiri Baraka, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, and many others — who transformed American literature by drawing as much from the blues and jazz idioms as they did from the European literary tradition.

Mr. Coltrane and Ms. Holiday, as well as countless other jazz and blues musicians, helped create and shape America’s greatest contribution to world culture in the 20th century. Black freedom fighters such as Mr. Douglass were, at their core, American patriots, struggling to make the U.S. Constitution whole.

These pioneers, and countless others, were uniquely American — self-made Yankee Doodle Dandies — who couldn’t have sprung from any other country in the world, despite its flaws and failures.

Fortunately, younger people today hold a more affirmative view of the African-American experience than their elders. Like most other Americans, they may lack a sophisticated understanding of history. But they grew up in a popular culture that African-Americans have dominated — or at least influenced in large measure — especially in music.

The popular art of hip-hop, for example, has influenced an entire generation of Americans. White rappers have contributed to this American popular art form, but the best of them have approached the music with a reverence for the culture that created it, just as the most skilled white jazz musicians have done for generations with another musical genre.

Jazz great John Coltrane and other African-American artists added to the national identity.

In 1926, black historian Carter Woodson helped launch what was then called “Negro History Week” during the second week of February, marking the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. In 1969, black students at Kent State University proposed expanding the week to a month, and Kent State first celebrated Black History Month in February, 1970.

Mr. Woodson believed that African-Americans needed to understand their history and traditions to survive as a people, but understanding that history is important to all Americans, not just black Americans. Without that understanding, white people cannot really know what it means to be an American.

African-American history is, as Mr. Freeman has stated, American history. But until most Americans regard it as such in a full and reverent way, they will need a month to learn from it — even if it’s the shortest month of the year.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com, 419-724-6467, or follow him on Twitter @jeffgerritt.