COMMENTARY

Heroin epidemic younger, whiter, but addiction horrors unchanged

4/13/2014

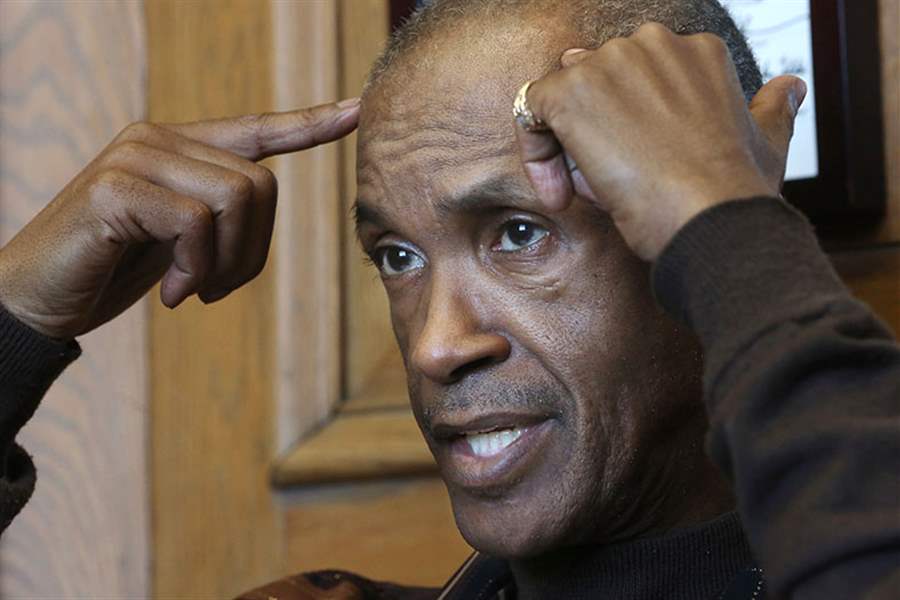

Substance abuse counselor Michael Flunder, 60, can’t — and doesn’t want to — forget the years of his struggle with heroin.

THE BLADE/KATIE RAUSCH

Buy This Image

Gerritt

“When you put the dope down, you’re going to meet yourself.”

— Michael Flunder of Toledo

Just before 7 p.m. on a Tuesday in late March, a dozen people linger in the parking lot of the Step One Club in West Toledo. A few hurriedly finish cigarettes before they march up a long flight of wooden stairs.

On the second floor they enter an oblong room, with dozens of chairs lined against the wall and circling a laminated table. As the meeting starts, every chair is taken.

This meeting of Heroin Anonymous, a fast-growing group in Toledo that formed this year, provides a snapshot of the city’s and state’s opioid and heroin epidemic. Of the more than 70 people here, 90 percent are white, and most appear to be in their 20s.

Many started with prescription painkillers such as Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet. Some are fresh out of rehab or still under court orders.

EDITORIAL: The politics of addiction

Based on federal estimates, at least 200,000 Ohioans are addicted to opioids such as heroin, including more than 10,000 in the Toledo area. State surveys of treatment centers also show that this epidemic has become far whiter and younger than it was in the 1970s or even a decade ago.

The demographics have shifted, but the dynamics of addiction remain the same: It’s a seductive, destructive, maniacal disease in which euphoric highs and miserable lows render a life unmanageable. In northwest Ohio, heroin-related deaths more than doubled last year — to 80, from 31 in 2012.

Even so, staying off heroin will be one of the toughest things the people in this room ever do. Most of them count their clean time in weeks, days, even hours. They’re looking for help and support.

A strapping man in a striped knit cap in his late 40s — one of the oldest in the group — says he has “as many years clean [six] as felonies.” His obsessions were not only heroin but also crack, alcohol, Benzos, fighting — “anything that was no good for me and as much of it as I could get.”

“I have a disease in the center of my brain, and I obsess,” he says. “My disease is real cunning. It tells me one Valium won’t hurt. As soon as I act on that, I’m defenseless.”

Several other people introduce themselves and share their stories and struggles. A 21-year-old woman fresh out of treatment talks about having to leave old friends and make sobriety the center of her life. No offense, she says to the handful of old-heads, “but I don’t want to be here when I’m 40 or 50.”

Another young woman talks about a recent relapse: “When I use now, I feel myself dying,” she says. “I don’t want people to have to come to my funeral.”

A baby-faced man who looks like a high school kid says the disease has humbled and beaten him. “I can tell someone how to live a good life but, when it comes to me, I got no answers,” he says.

In some ways, every addict’s story is the same: People start using opioids to feel good. As their tolerance for the drug rises with addiction, they eventually ruin their lives trying to feel normal or avoid the misery of withdrawal. Drugs take their money, pride, families, jobs, self-esteem, and sometimes, even their lives.

Michael Flunder believes he’s here only by the grace of God. An addict for 20 years, Mr. Flunder, 60, works as a substance abuse counselor in Toledo and comes to Heroin Anonymous every Tuesday and Friday. Clean for nearly two decades, he hasn’t forgotten his years of using.

He doesn’t want to forget.

A small, almost frail-looking man at 5 foot, 8 inches and 128 pounds, Mr. Flunder possesses the self-assurance and strength of someone who has gone to hell and back and lived to tell about it. And tell about it he does, his brown eyes burning.

“Much has been given to me,” he says. “I’ve been entrusted with a responsibility. I can’t keep this in. I have to talk about what God has done for me.”

Mr. Flunder grew up in a working-class family of 11 children. His father worked for the railroad. After graduating from Scott High School in 1972, Mr. Flunder attended college, became a union plumber, and later, worked for the city of Toledo water department.

Substance abuse counselor Michael Flunder, 60, can’t — and doesn’t want to — forget the years of his struggle with heroin.

He started snorting heroin in 1976. “Peer pressure,’’ he says. Most of his friends were using heroin. By the time the city hired him in 1979, he was shooting the drug.

Mr. Flunder always worked and made good money but spent $60 a day on heroin. “I was shooting my whole check,” he says.

In 1985, he started smoking crack cocaine too, after a girlfriend turned him on. After crack jacked him up, he needed heroin even more to come down.

With drugs tapping him out, Mr. Flunder sometimes slept in vacant buildings, cars, or dope houses. His mother wouldn’t let him in her house.

During a fight with another addict in 1987, Mr. Flunder’s face was pounded with a hammer, leaving him with a steel plate behind his left eye. In 1994, he was robbed twice in one night, after cashing a $5,000 tax-refund check.

Between 1985 and 1996, Mr. Flunder went to treatment 32 times: residential, detox, outpatient. He went to Flower Hospital, Compass, Toledo Hospital, and other treatment centers but always relapsed.

In 1996, drugs finally cost him his job with the city after he dropped dirty, testing positive for drugs for the third time. That year, Mr. Flunder also was arrested for receiving stolen property.

Lucas County Common Pleas Judge James Bates gave him probation, including regular drug tests. A positive test would have meant jail, and Mr. Flunder didn’t want to go to jail.

Step two of the 12-step program states that “A power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” In Judge Bates, Michael Flunder found it. “God used Judge Bates to get my attention,” he says. “That was my nuclear blast.”

On Jan. 20, 1997 — his “anniversary” — Mr. Flunder stopped using heroin and all other drugs for good.

A disciple of the 12 Steps, Mr. Flunder says addicts needs a spiritual awakening to fill the void that drugs leave. If not, their obsessions will persist, even after they stop using.

Last year, an addict Mr. Flunder knew who was clean for 25 years relapsed. A few weeks later, he killed himself with a chain saw.

“As addicts, the greatest damage we do is to our spirits,” he says. “You not only have to quit using, you have to address your problems. Otherwise, the void can drive you crazy. When you put the dope down, you’re going to meet yourself.”

Addicts typically hit bottom before they’ve had enough. By learning from others, Mr. Flunder says, young addicts can “raise the bottom” and not have to fall as far.

Mr. Flunder has worked as a substance abuse counselor since 1999. Getting addicts into treatment is harder today than it was 20 years ago, he says; Ohio needs more treatment centers so that addicts can get help when they ask for it.

A few weeks ago, Mr. Flunder tried to get an addict into treatment, calling every center and hospital in Toledo. Some were full. Others wouldn’t take the addict’s insurance.

‘As addicts, the greatest damage we do is to our spirits,’ Michael Flunder says. ‘You not only have to quit using, you have to address your problems.’

Waiting lists and delays plague opioid treatment centers throughout Ohio. Drug treatment centers reach only one in 10 of those who need treatment, the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services reports.

“I couldn’t get him in,” Mr. Flunder says, “and I ain’t heard from the guy since. When someone has a moment of clarity and wants help, you need to help him.”

Mr. Flunder continues to help other addicts recover. That’s why he’s here tonight at Heroin Anonymous.

He raises his hand, stands, and speaks of things that, for most, are unspeakable: the beatings, the betrayals, the slimy self-hatred, the merciless cravings, the crushing humiliations of addiction.

But Michael Flunder has been clean for 17 years, two months, and five days, and his voice rises from a place of horror and hope.

Jeff Gerritt is The Blade’s deputy editorial page editor.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com, 419-724-6467, or follow him on Twitter @jeffgerritt.